Qatar has warned governments they risk “shooting yourself in the foot” if they do not signal greater support to international energy companies and accept that gas needs to be part of the transition to meet carbon net zero goals, a Financial Times report said.

Saad al-Kaabi, the gas-rich Gulf state’s energy minister, told the Financial Times he expected that the global gas shortage, which has spread from the UK and Europe to other regions, to last a “few years” as demand outstrips supply.

He blamed low volumes of gas in storage globally, surging demand in Asia and a lack of investment in new and existing gas and oil projects over the past five years as energy companies come under pressure to reduce emissions.

Kaabi, who this week met Boris Johnson, UK prime minister, and Kwasi Kwarteng, business secretary, said that while it “looks great as a politician to say ‘I’m going to reach net zero by 2050’,” there was “no way the world can get through a realistic energy transition without adding more gas into the mix”.

“If that is not realised and not embraced as part of the solution, you are going to have more problems and spikes like we’ve had, because then you are demonising the people who can help you,” said Kaabi, who is also chief executive of state energy group Qatar Energy.

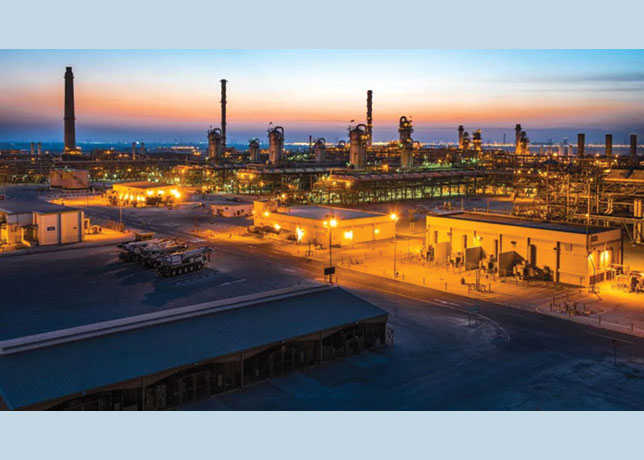

Qatar is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas and is the majority owner of South Hook LNG terminal in Wales, which has the capacity to supply a fifth of the UK’s gas needs. Last year it also secured rights for storage and redelivery capacity at the UK’s Grain LNG terminal in Kent, for 25 years beginning from 2025.

But South Hook is operating under capacity as demand from Qatar’s Asian customers means that the Gulf state is diverting LNG to its biggest clients. The British government no longer lists Qatar among its main suppliers.

Kaabi said the key difference was that in Asia most gas was procured by state companies or state-affiliated entities that agree to fixed, long-term contracts to ensure energy security while, in the UK and Europe, LNG is bought by private sector companies, mostly on spot markets.

“Asia is just going to pull [demand] . . . it’s going to be an arbitrage between who is going to be paying more and the market dynamic works itself out,” he said. “But that’s why we need to support more supply of gas otherwise you are just shooting yourself in the foot.”

About 70 per cent of Qatar’s LNG output goes to Asia.

Kaabi said Qatar would examine how it could supply more gas to the UK, adding that “we need to analyse the problem in order to put a solution in place”.

He said Europe needed to “give a clear signal” about whether “they want more investment in gas and additional supply from Qatar or not”. The European Commission in 2018 opened an investigation into whether Qatar’s long-term contracts were in breach of EU antitrust rules.

Kaabi, who had a virtual meeting with the EU’s energy commissioner this month, said the case had “no basis”.

“We have mixed signals from Europe,” he said. “We need to understand if we are welcome in Europe, or not welcome.”

With levels of LNG storage low around the world for the time of the year, he said he was concerned that there was not enough time to replenish stocks before winter.

“I’m worried about storage and the winter — supply is the fundamental issue,” Kaabi said. “Is it bad planning or is demand increasing much quicker than people expected? I think that is probably more likely what’s happening.”

The critical issue was for governments to signal to energy companies that gas would be included in their plans to move to carbon net zero, he said.

“All the environmentalists are just clobbering [them]. Most of the IOCs are saying ‘we are going to decline our oil production by x, and so on and go into renewables,” Kaabi said. “Some oil companies, I don’t know if they are oil companies any more . . . that’s fine but are there enough players to keep us fuelled as humanity?”

Qatar Energy has been one of the few companies investing heavily in gas in recent years. It is spending almost $30bn expanding its North Field, the world’s largest gasfield, to raise its annual production capacity from 77m tonnes of LNG to 110m by 2025. A second phase is expected to increase it to 126m tonnes by 2027.

But with gas demand forecast to grow at 2-4 per cent a year to 2050, he said “people are not investing enough to catch up with that 2 per cent”.

“The second issue, which is the more dangerous one people don’t talk about . . . is huge investment needed in fields that already have gas and oil,” Kaabi said. “It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pay attention to the environment and not want to achieve the Paris accord, we need to do that . . . [but] there is no scenario where you don’t have gas, because gas has to be the baseload.” --Reuters