GHGs ... little progress on cutting emissions

GHGs ... little progress on cutting emissions

Facing an uphill task of not just setting more ambitious targets, but also to deliver on all commitments made, the world will require a wide-ranging, large-scale, rapid and systemic transformation, says a UN report

The United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) annual Emissions Gap Report has been sounding warning bells for years about a nearing tipping point in climate change, making a call for the rapid transformation of societies.

Now in its 13th year, the report provides a yearly review of the difference between where greenhouse gas emissions are predicted to be in 2030 and where they should be to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The ‘Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window – Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies’ finds that urgent sector and system-wide transformations are immediately needed to avoid climate disaster.

Lamenting procrastination by global nations, Inger Andersen, UNEP Executive Director, has called for a system-wide transfor-mation to curb rising greenhouse gas emissions.

“To get on track to limiting global warming to 1.5 deg C, we would need to cut 45 per cent off current greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. For 2 deg C, we would need to cut 30 per cent.”

SLOW PROGRESS

The report noted that very limited progress had been made since COP26 was held in Glasgow held last year.

It said countries are off track to achieve even the globally highly insufficient nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

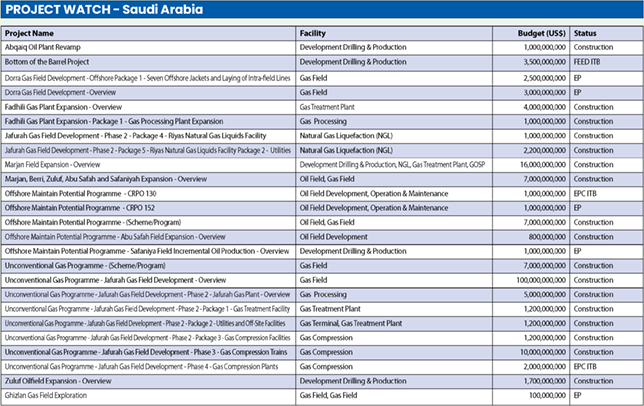

Global GHG emissions in 2030 based on current policies are estimated at 58 gigatons of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e). The imple-mentation gap in 2030 between this number and NDCs is about 3 GtCO2e for the unconditional NDCs, and 6 GtCO2e for the condi-tional NDCs.

The world did see an unprecedented but short-lived reduction in emissions during the Covid-19 pandemic when total global GHG emissions dropped 4.7 per cent from 2019 to 2020. This was due to a sharp decline in CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry of 5.6 per cent in 2020.

However, CO2 emissions rebounded to 2019 levels in 2021 to levels exceeding 2019’s.

The rate of growth in GHG emissions has slowed in the past decade, but global GHG emissions could set a new record in 2021. Emissions growth was 1.1 per cent annually between 2010 and 2019, slower than 2.1 per cent between 2000 and 2009.

Thirty-five countries accounting for about 10 per cent of global emissions. The top seven emitters: China, the EU27, India, Indone-sia, Brazil, Russia and the US, plus international transport accounted for 55 per cent of global GHG emissions in 2020.

Collectively, G20 members are responsible for 75 per cent of global GHG emissions.

According to annual per capita emissions, the US with 14 tCO2e remains far above the global average of 6.3 tCO2e. It is followed by 13 tCO2e in Russia, 9.7 tCO2e in China, 7.5 tCO2e in Brazil and Indonesia, and 7.2 tCO2e in the EU.

India remains far below the world average at 2.4 tCO2e. On average, least developed countries emit 2.3 tCO2e per capita annually.

WORLD FAILS TO KEEP UP WITH PLEDGES

A continuation of the level of climate change mitigation effort implied by current unconditional NDCs is estimated to limit warming over the 21st century to about 2.6 deg C with a 66 per cent chance.

Meanwhile, continuing the efforts of conditional NDCs lowers these projections by around 0.2 deg C to 2.4°C with a 66 per cent chance.

However, in most cases, neither current policies nor NDCs currently trace a credible path from 2030 towards the achievement of national net-zero targets.

Globally, 88 parties covering approximately 79 per cent of global GHG emissions have now adopted net-zero targets. This is up from 74 parties at COP 26.

Focusing on the G20 members, 19 members have committed to achieving net-zero emissions, up from 17 at COP 26.

SECTOR CHANGES

The food system is currently responsible for about a third of total GHG emissions, or 18 GtCO2e/year. The largest contribution stems from agricultural production (7.1 GtCO2e, 39 per cent) including the production of inputs such as fertilizers, followed by changes in land use (5.7 GtCO2e, 32 per cent), and supply chain activities (5.2 GtCO2e, 29 per cent).

Projections indicate that food system emissions could reach ca 30 GtCO2e/year by 2050.

Transforming food systems is not only important for addressing climate change and environmental degradation, but also essential for ensuring healthy diets and food security for all.

A global transformation from a heavily fossil fuel- and unsustainable land use-dependent economy to a low-carbon economy is expected to require investments of at least $4–6 trillion a year, a relatively small (1.5–2 per cent) share of total financial assets man-aged, but significant (20–28 per cent) in terms of the additional annual resources to be allocated.

This will not be easy, given the many other pressures on policymakers at all levels.

However, climate action is imperative in all countries but must be achieved simultaneously with other UN SDGs.