Shipping was reponsible for 2 per cent of CO2 global emissions in 2020

Shipping was reponsible for 2 per cent of CO2 global emissions in 2020

Policymakers are considering ways to encourage the shipping industry to use low-carbon modes of transportation.

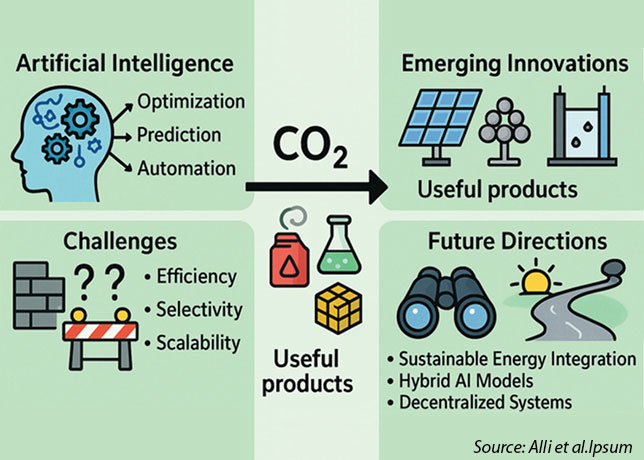

Shipping is frequently cited as one of the most effective modes of transportation in measuring emissions per ton transported per kilometer. However, throughout the years, the demand for maritime transportation has grown quickly, which has led to a correspond-ing rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the shipping industry.

Around 765 million metric tons (Mt) of carbon dioxide (CO2) were released into the atmosphere by international shipping in 2020, or roughly 2 per cent of energy-related CO2 emissions worldwide. This was around 1.2 per cent less than the previous year, when emissions peaked at 774 Mt CO2.

Any forecasts of shipping emissions are heavily dependent on a variety of factors, such as fleet expansion and demand, vessel ef-ficiency advancements, and the introduction of new technology.

According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), shipping-related emissions in 2050 are predicted to vary from 1,200 Mt CO2 per year in the low-emission scenario to 1,700 Mt CO2 per year in the high-emission scenario.

Along with all other industries, shipping faces pressure to cut emissions in order to reach decarbonisation goals in the coming dec-ades.

The first GHG plan for the IMO was adopted in April 2018. In order to achieve the IMO's goals of reducing CO2 emissions per transport (as an average across international shipping) by, at least, 40 per cent by 2030 and pursuing a 70 per cent reduction in car-bon intensity while pursuing 50 per cent reductions in absolute global GHG emissions by 2050, compared to 2008.

Some nations and a number of shipping businesses believe the IMO's new technical and operational regulations are insufficiently ambitious to reduce GHG emissions from international shipping in the long term.

Through the use of the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), the short-term actions aim to increase the worldwide fleet's average yearly efficiency by roughly 2 per cent between 2020 and 2026.

This was barely an increase above the 1.6 per cent growth between 2000 and 2017. Government regulations and incentives will be a crucial component in assisting shipping in achieving its 2050 goals for decarbonisation.

The importance of the larger maritime supply chain in achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement was reemphasised during COP26 in Scotland last year, which brought attention to shipping's involvement in the production of global emissions and its ability to aid in mitigation efforts.

Led by Denmark, 14 nations issued the ‘Declaration on Zero Emission Shipping by 2050’.

The declaration called for rapid reductions to enable shipping to reach zero emissions by 2050 and was signed by important ship-ping nations including the US, UK, Germany, France, and Norway as well as important participants in the industry like Panama.

Zero emissions does not, nevertheless, mean that there are no carbon emissions in the strictest sense; rather, if it follows declara-tions from other transport sectors, the goal is more likely to be net-zero emissions, which is frequently backed up by the creation of offsets like carbon sinks (such as trees) or through carbon capture.

Alternative fuels are anticipated to have the greatest impact on lowering GHG emissions and will play a significant part in the de-carbonisation of the marine and offshore sectors. Shifting measurement criteria to the latter is thought to be crucial for achieving net-zero emissions for shipping because the current regulatory framework concentrates on emissions generated during the full life cycle of the fuel (well-to-wake) rather than those generated during the tank-to-wake emissions.