Acts of sabotage on Yemen’s oil and gas infrastructure have accelerated

Acts of sabotage on Yemen’s oil and gas infrastructure have accelerated

AFTER another year of attacks to its energy infrastructure and a violent start to 2014, Yemen’s oil production has declined to its lowest level in years.

Continuing sectarian battles in the north, tribal unrest in the east, a secessionist movement in the south, and ongoing activities by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) make Yemen one of the Middle East’s politically most challenging operational environments for domestic and international oil companies.

Amidst the political crisis, Yemen has managed to conclude the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) to work on a new constitution and introduce a more federalist state structure. Implementing the NDC’s recommendations will be difficult given the competition for power and revenue allocations between the central government and its peripheries. It remains questionable whether the NDC’s suggestion to create a new federal structure will reduce separatist demands in the south.

Political instability and attacks on physical energy infrastructure will remain a key risk in Yemen. The country’s latest licensing round, announced in August 2013, offered onshore and offshore blocks but has not raised sufficient interest from international oil companies. Investor interest in Yemen’s hydrocarbons sector will be further tempered if current efforts to increase the state’s role in the sector persist, as state-owned companies PetroMasila and Safer are seeking larger interests in energy projects.

NEW STRUCTURE SOLVES LITTLE

The Yemeni government approved a new federal structure on February 10 that divides the country into six provinces and will ostensibly allow for greater decentralisation. The announcement came on the heels of a 10-month National Dialogue Conference (NDC) intended to ease political divisions between rival political groups, tribes, and power centres following the popular uprising that resulted in the ousting of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh in 2011. The NDC’s conclusion also permitted a one-year extension of the mandate of current president Abdurabu Mansour Hadi, whose two-year transitional term was set to expire in February.

The federal structure was meant to address calls for greater autonomy in the south as well as the far north, but has already been rejected by several groups in both regions. Although the NDC did manage to bring together representatives from the ruling party, the official opposition, southern separatists, youth activists, and the Houthis (a Shia group in the north seeking to create an autonomous region), key leaders from the south boycotted the talks. Southerners have attacked the new structure, as it divides former southern Yemeni provinces across two regions, separating Aden, Dali, and Lahij from Hadhramawt province.

NORTH-SOUTH ISSUE

The Socialist party-ruled People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in the south voluntarily unified with North Yemen in 1990 but tensions resulted in a civil war in 1994. Since the end of the war, the larger-populated north has emerged as the dominant partner with southern leaders complaining about persistent political and economic marginalisation.

Although economic challenges such as high unemployment exist across the country (40 per cent of men aged between 20 and 24 are unemployed, according to government data), people in the south are looking back to an economic model where the state provided more extensive employment, education services, and food subsidies.

Southerners have particularly complained in recent years that the south has lost out on investment and development opportunities because the central government in Sanaa has no interest in a prosperous south, in spite of taking advantage of its hydrocarbons resources.

Opponents of Yemen’s new federal plan, which would split the country in six and the south into two provinces, fear that it represents a new phase of divide and rule – as was practised under Saleh – designed to keep Sanaa powerful and the regions weak. Regardless of intent, the reaction clearly suggests that the plan has not solved the fundamental structural issues facing the state or assuaged any mistrust between political groups.

Under these conditions, political tensions between the central government and the regions will continue and possibly exacerbate separatist sentiment. Militant elements within the southern separatist movement are already involved in a low-level insurgency, and will be increasingly likely to target the energy sector if initial attacks against state assets and security forces fail to secure political concessions.

Meanwhile, the northern-based Houthis will continue to add a sectarian dimension to the central government’s struggle to keep the regions under its control.

SECURITY RISKS TO REMAIN HIGH

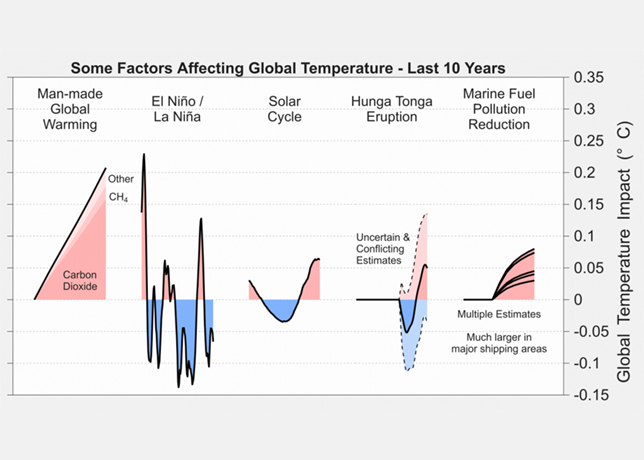

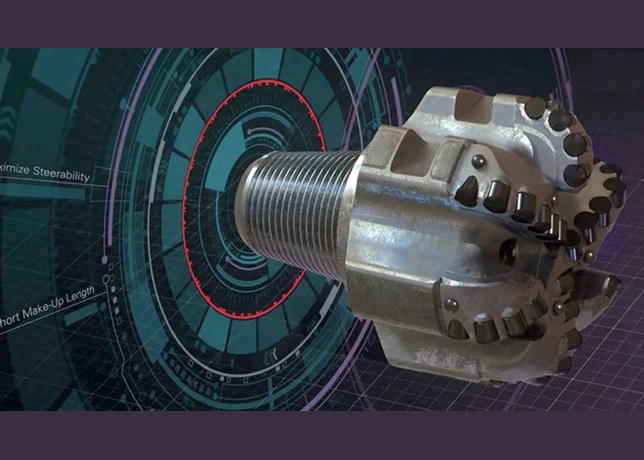

Continued political divisions will ensure that security risks in the oil and gas sector remain high. Frequent acts of sabotage on Yemen’s key oil and gas pipelines since Saleh’s removal from power have accelerated what was already a steady decline in hydrocarbon production over the past decade, largely due to a lack of investment.

Yemen’s oil production fell from 455,000 barrels per day (bpd) in 2001 to 228,000 bpd in 2011; over the past two years, output dropped even more precipitously, to under 170,000 bpd in 2013. Attacks on pipeline infrastructure have typically been carried out by tribesmen seeking to pressure the government into making political concessions or releasing prisoners, as well as opportunistic “for profit” extortion. Groups affiliated with Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) have also launched attacks as a means of discrediting the government and disrupting a key source of revenue. Armed tribesmen again targeted Yemen’s main oil pipeline, the 270-mile Ma’rib-Ras Isa line, earlier, disrupting crude flows to the Ras Isa export terminal less than a month after it was repaired. This attack follows a string of more than 50 separate strikes on pipelines across Yemen in 2013. Violence has also become more widespread, with the Hadramawt Tribal Confederacy in the southeast of the country setting up roadblocks at energy facilities as well as bombing pipelines. The confederacy is calling for the replacement of the predominantly northern military oil protection force with a locally recruited force.

The number of incidents of sabotage is likely to increase in Ma’rib, Shabwah, and Hadramawt provinces as political actors position themselves within Yemen’s new federal system. Energy assets in the Masila Basin will remain less affected than those in Ma’rib, but tribal unrest, the ongoing military campaign against jihadists, and a likely southern insurgency, will continue to be risks to energy infrastructure and could disrupt oil flows in 2014.

ECONOMIC FRAGILITY

This violence will undermine the already weak economy, which has become more fragile due to the dramatic fall in hydrocarbons output. IHS estimates that the Yemeni economy grew just 3 per cent last year, as declining hydrocarbon production took its toll. This is lower than the government’s own figures, which state that Yemen’s economy grew by 5.4 per cent last year. The country’s current account and fiscal balances have also suffered. Declining crude oil exports contributed to a widening of the current-account deficit to nearly 8 per cent of GDP in 2013, from 3 per cent of GDP in 2012, including grants (Saudi Arabia provided a $1-billion deposit into the Central Bank of Yemen in September 2012 but not in 2013).

Meanwhile, the government budget has fallen into further deficit, which IHS estimates at over 7 per cent of GDP in 2013. Oil minister Ahmad Dares said in December 2013 that sabotage had cost the country $4.75 billion between March 2011 and March 2013, which represents about 14 per cent of 2013 nominal GDP based on IHS estimates.

ATTRACTING INVESTMENT INTO O&G

The growing economic pressure and lack of technological capacity mean that Yemen’s central government is keen to attract foreign investment to its oil and gas sector. In January 2013, the government announced that oil reserves were higher than previously estimated, and subsequently launched the country’s sixth bidding round in August 2013. Of 45 companies that submitted pre-qualification applications, the government approved 18 companies to bid on nine onshore and 11 offshore hydrocarbons blocks.

In particular, Sanaa hopes that foreign operators will be more interested in developing the offshore blocks, which are insulated from some of the onshore physical security risks but exposed to potential threats such as piracy in the Gulf of Aden given the proximity to Somalia’s coast.

At the same time, however, the government is seeking to extract additional revenue from producing blocks. In recent years, the state has increasingly transferred blocks to state oil companies when international oil companies’ licences have expired. Two of these companies, PetroMasila and Safer, are keen to increase their stakes in current joint ventures: PetroMasila is targeting shares in Total’s licence in Block 10 and Dove’s Block 53, while Safer is planning to take over operatorship Block 5 from Kuwait Energy.

The two state companies are aiming to operate around 80 per cent of the country’s current production of 200,000 bpd, up from zero a decade ago (when Yemen was producing around 400,000 bpd). The government is also seeking to renegotiate gas export contracts to secure higher payment. It is particularly keen to push Total, the largest foreign operator in the country, to pay a higher price for its LNG exports. Given that it was successful in a similar effort with the Korean firm Kogas, it is likely that Total will follow suit.

OUTLOOK AND IMPLICATIONS

The official close of the NDC was a step in the right direction as it brought strongly opposed political groups around the same table to chart a course for Yemen’s future. The new federal system will need to include the concerns and grievances of southerners and the northern Houthis. If not, political violence and an outright call for southern independence will exacerbate the violent conflict between power centres and increase security risks.

In this context, Yemen’s current administration and any future central government will need to reassure foreign oil companies that the ongoing political instability will not dissuade companies from investing in the country’s oil and gas blocks as this would affect Yemen’s oil and gas production and reduce state earnings in the short to medium term.

Although the risk of outright nationalisation remains slim in Yemen, due to the continued need for investment and technological capacity, government efforts to bring more operated oil and gas production under state control and to renegotiate a larger share of rents are likely to dampen investor enthusiasm in the medium term – putting potentially renewed downward pressure on production over the longer term.