Baroudi … collective action

Baroudi … collective action

The US, China, Russia, EU, Japan, Saudi Arabia and global institutions like WB and IMF have a big role to play to keep the global pandemic and oil glut from producing long-term damage, writes Roudi Baroudi, CEO of Energy and Environment Holding

It took a global pandemic that has grounded airlines, idled factories, and kept billions of people indoors, but prices for some oil futures contracts have gone into negative territory for the first time ever.

Ever think about that? Not since Colonel Drake struck oil – with commercially viable methods – in Pennsylvania in 1859, has a producer had to pay customers to take crude off their hands.

Together, oil and gas still supply approximately 60 per cent of the world’s energy, and that is not to mention its myriad other uses in modern industry. So what to do when a demand slump of unprecedented size and speed has brought so low the world’s most ubiquitous commodity, one still required by so many people?

First, it is crucial to recall how we got here, specifically the fact that the Covid-19 crisis was not the only factor. Keep in mind that for weeks, the gathering collapse of demand coincided with a massive flow of oversupply as Russia and Saudi Arabia refused to agree on production cuts, choosing instead to battle for market share going forward.

Eventually they and other producers reached a new entente, but this was too little, too late: the effect of the virus had so destabilised the markets that even zero was no longer a floor in the minds of spooked investors.

The basics are as follows. Until Covid-19 shut down whole sectors in the global economy, the world had been consuming approximately 100 million barrels of oil per day (mbpd). By mid-April, that figure had dropped to something in the order of 80 mbpd. The imbalance quickly filled up tank farms, and some analysts believe that as much as 160 million barrels of oil are currently being stored in tankers at sea but with nowhere to go because there are far fewer customers.

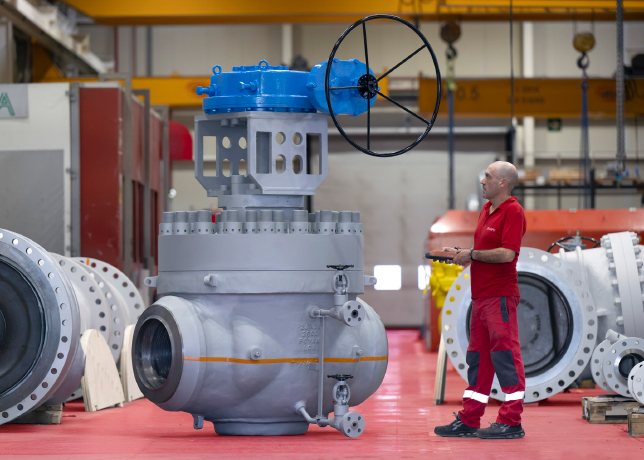

Airlines have slashed their schedules by 90 per cent or more. Refiners can’t sell their output and have stored up all the crude they can. Inevitably, oil-producing companies have had to shut down their wells, and dozens of refineries have had to suspend operations as well since they could no longer dispose of oil and related products.

There is no question that the heaviest damage has been sustained in the US. There, the shale oil business had been so successful that the country had become the world’s largest crude producer, managing not only to satisfy 90 per cent of its own demand from domestic sources, but also to compete with Russia and Saudi Arabia, among others, for customers overseas.

The industry was always vulnerable, however, because of higher production costs, so when prices started to slide, its producers – most of them relatively small companies with little capacity to ride out rough patches – were the first to fail. And they will continue to do so, in their hundreds, for the next several months.

Consider the impact of all this. Oil is unlike any other commodity in that a safe, affordable, and continuous supply of it is perhaps the single-most far-reaching factor of modern life for families businesses, organisations, and almost 200 countries around the globe.

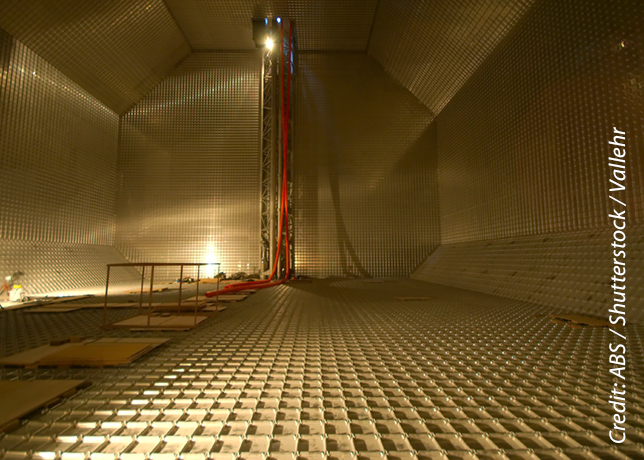

|

Covid-19 has forced several companies to shut down their wells, and refineries to suspend operations |

Of course, renewables and other alternative sources have made great strides in recent years, and one or more of these technologies will be the future, but for now, and hydrocarbons in general – and oil in particular – are still the prime determinants of success or failure.

At the same time, the fact that the oil crisis is having such a concentrated effect in the US is a double-whammy because that country – a great power in a class by itself – is such a reliable bellwether for global economic health.

Even as China’s meteoric rise over the past couple of decades has made it the world’s second largest economy, with nominal GDP about $14 trillion for 2019, the US economy remains far away the world’s heftiest at about $21 trillion. For this reason, when Americans stop buying, everyone, everywhere, loses sales – of everything.

And now, in just a few short weeks, more than 26 million of them have filed for unemployment benefits. Jobs are being shed in record numbers elsewhere, too, including Europe, Asia, meaning less capacity for anyone else to compensate for the evaporation of US demand – for everything.

As though all this were not enough, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has now warned that with parts of East Africa and South Asia already stalked by crop failures due to locust infestation and severe drought, respectively, the Covid-19 crisis could exacerbate food shortages and lead to famines of ‘biblical proportions’. Billions of people around the world could soon find themselves facing malnutrition, with many millions threatened by actual starvation.

The worst thing about these overlapping crises is that each is virtually unprecedented in its own right, never mind its juxtaposition with other so-called ‘black swans’. This makes them less susceptible to remedies than more commonplace problems and, therefore, almost certain to require more than simply waiting for the markets to correct themselves. By the time that happens we could be in the middle of an historic human catastrophe.

So how do we keep the combination of global epidemic and global oil glut, which has already inflicted a period of unprecedented stress, from producing long-term damage that yields to even more human and economic losses? How do we get the world’s most important economic engines – especially the US, China, and Europe – to get global commerce moving again? In a word, unity – of the sort that brings all humankind together for collective action.

Even if we do everything right, it will take months at least, and possibly a year or more, to stabilise the situation. Even assuming that a vaccine is developed that stanches the toll in human lives, the damage done to some of the world’s most important economies will not be repaired overnight. Until stability and confidence are restored, the whole world will be a fragile place in which rumours and/or tensions can wreak socioeconomic havoc on millions or even billions of people.

In short, recovery depends on sincere dialogue, full cooperation, and genuine transparency. We are all in this together now, so the best way out is to collaborate on an exit strategy that saves time, money, and – most important of all – human lives.

The biggest responsibility falls on the biggest players, namely the US, China, and Russia, along with the EU, Japan, and multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Given its unusually large role in the oil business, Saudi Arabia also has a role to play in any attempt to restore economic stability. Going forward, each of these countries and entities will need to make – and keep – commitments about what it will and will not do. Only then can the necessary confidence and stability be rebuilt around the world.

Exceptional challenges call for exceptional remedies, and this definitely qualifies. Already we have seen a virtual meeting at which several global leaders pledge to work together on a vaccine, but the US was notable by its absence.

For the broader purpose of steering a way out of the global economic morass, it is essential that Washington be present and accounted for.

My own suggestion is an emergency (again, probably virtual) meeting of the G20 at the earliest available date, which probably means the first part of May. Not a moment should be wasted in preparing a realistic agenda that measures up to the enormity of the tasks at hand.

Never before has the entire world faced common challenges of such deadly and pernicious qualities, but nor have we ever had so much capacity to work together. Our choice, then, is clear: make use of the later or be undone by the former. To quote the quintessential American, Benjamin Franklin, 'we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately'.

Whatever one’s worldview, few will question the need for Washington to play a global leadership role, as it has on multiple occasions over the past several decades. History shows that when it does so early in the game (for example, the 2008-2009 economic meltdown), the damage can be limited. It also demonstrates that when US involvement is delayed (see World War II), the scale of losses – human, financial, even civilizational – can be unimaginable.

Roudi Baroudi is CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha.