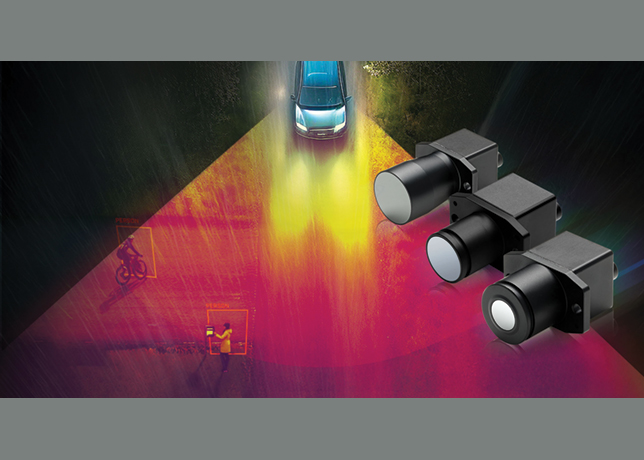

Hosie and Ferrante (right)... reviewing supply chain contracts

Hosie and Ferrante (right)... reviewing supply chain contracts

Jonathan Hosie and Pablo Ferrante, partners in the Mayer Brown global law firm, tell OGN how oil and gas businesses can mitigate their exposure to financial losses where their global supply chains are disrupted

From a legal perspective, the starting point will be to review the relevant supply chain contracts. These may span more than one jurisdiction, with correspondingly different legal codes applicable to their interpretation and application.

Some of these contracts will provide for formal disputes to be referred to arbitration and others may mandate litigation in the applicable local courts.

A proper analysis of these issues is likely to reveal some challenges but there may also be opportunities, for instance in being able to leverage the benefits of local laws and obtain first mover advantage if a formal dispute is inevitable.

UNFORESEEN PANDEMICS

If your suppliers are unable to supply because of the pandemic, does that relieve you of your obligation to supply to your customer?

When reviewing your contracts, one obvious consideration will be whether the contract contains any express provisions that may excuse or suspend the obligation to perform. This may be in the form of a provision defining a materially adverse change or an event of force majeure.

Many supply chain contracts will contain express force majeure provisions, which relieve the affected party of its performance obligations. However, it is important to note that whilst force majeure is a recognised concept in civil law jurisdictions (where it will be written into the local civil law code and typically apply by default to supplement the parties’ contractual provisions), the concept of force majeure is not part of the common law, which applies in the UK and its former Commonwealth jurisdictions that follow similar common law principles.

Therefore, in common law jurisdictions, legal effect will be given effect to the contractual force majeure or material adverse change provision only as written in the particular contract, and the outcome will depend on how widely or narrowly the clause has been drafted. In common law jurisdictions, a force majeure provision will generally not be implied.

Before the arrival of this current pandemic, not all force majeure clauses were drafted with such matters in mind. It may be that the list of force majeure events are set out in exclusive terms, and the categories of unforeseen risks are such that the effects of the pandemic do not obviously fit. It is in these circumstances that parties need to consider the impact of the governing law of the contract.

If this is based on the common law, there is probably less scope for relief than is available in civil law jurisdictions. This is because the common law doctrine of frustration is stricter in its application and harder to satisfy compared to force majeure, which is a concept that is not part of the common law.

In contrast, in civil law countries there might be additional remedies to address unforeseen circumstances, beyond the remedies provided by the contract itself. Such civil countries include all of South America, almost all European countries, China and Japan.

In China, for instance, the Contract Law of the PRC incorporates a statutory form of force majeure, exempting contractual performance where impacted by factual circumstances that could not be foreseen, avoided and surmounted.

China also has the doctrine of fundamental change of circumstances, where there is found to be a significant change which could not have been foreseen but renders performance manifestly unfair to the relevant party or renders it impossible to realise the goal of the contract. In these circumstances, the contract terms may then be varied by the People's Court.

In the Middle East, legal systems are generally based on a combination of common law, civil law, statutory and sharia law. In these jurisdictions, whilst express force majeure provisions will often be included in the contract, their application falls to be assessed against the backdrop of sharia law. This also has concepts similar to the doctrine of fundamental change of circumstances.

In addition, certain countries have introduced emergency legislation in light of the pandemic which adds a further layer of protection (or interference) with the parties' contractual bargain.

RENEGOTIATING EXISTING CONTRACTS

Another option to consider is to negotiate for re-setting the basis of the existing contractual arrangements to cater for the now known impact of the pandemic. This may involve re-allocating the risk of labour shortages and/or delayed delivery of components on the time and cost of completing the contract. It maybe that the party affected is allowed an extension of time and relief for liquidated damages but bears the cost of the increased resources necessary to comply with applicable restrictions on working methods imposed by local laws. If you go down this route, consideration should also be given to expressly waiving certain rights and/or reserving others.

NEW CONTRACTUAL FRAMEWORKS

The need for stronger and more diverse supply chains in the oil and gas sector is now apparent. This will require new contracts with a larger number of suppliers in different locations providing key components and supplies, as well as greater customer-choice flexibility. What happens if there are local spikes in the pandemic leading to local restrictions; should this allow the purchaser to switch to an alternative supplier?

The force majeure provisions will no longer be regarded as standard boilerplate but will now have to be carefully structured and the formal electronic execution of contracts will now become the default position, in the place of in-person wet signatures.

DISPUTE MANAGEMENT

If a formal dispute is inevitable, consider starting the process first. This may be particularly important where litigation in the local courts of your counterparty may be undesirable (or your local courts are likely to give your company at fairer hearing). Even starting an arbitration first can have its benefits, in terms of defining the issues to be determined by the tribunal.

The specific wording on your particular contract matters. If you are invoking force majeure, prompt and preventative action is best practice, and you should consider alternatives, including partial performance. If you are resisting force majeure, make sure to communicate rejection notices promptly and remember your duty to mitigate damages.

Another factor to consider is whether your local court system is capable of processing the resolution of the dispute within an acceptable timeframe; in many jurisdictions the enforced closure of Court buildings has caused a backlog whereas all the main arbitral institutions have remained functional (albeit remotely) during the pandemic.

SUMMARY

The fragility of global supply chains has been exposed by the pandemic and businesses operating in the oil and gas sector have faced some serious challenges with the fallout. However, there are lessons to learned from the global impact, some of which we have addressed above. In our experience, clients, who take care to analyse properly the risks presented by these events, are better able to seize the opportunities that also exist.