WindWings could be an answer to the call for decarbonisation in shipping

WindWings could be an answer to the call for decarbonisation in shipping

The Middle East’s shipping industry needs to get ahead of the decarbonisation curve by investing into technology, which will futureproof it from regulatory shifts, John Cooper, CEO, BAR Technologies, tells OGN

If it were implemented today, the IMO’s new Maritime Research Fund would likely cost Middle Eastern shipowners and charterers over $10,000 a year per ship.

The IMRF is an initiative led by global shipping representatives which aims to raise $5 billion to support developing countries' decarbonisation and maritime research and development. The fund would operate via a $2 levy per tonne of marine fuel consumed, to be paid for entirely by industry at no cost to governments.

It’s a proposal that continues to place pressure on shipowners and charterers to fund maritime decarbonisation, and while it will require a few more years of negotiation, the proposal (if accepted) would still come into force well within the operational lifespan of the current fleet.

According to UNCTAD’s 2021 Review of Maritime Transport, the Middle East’s combined shipping fleet comprises around 3,500-4,000 ships.

An MR2 tanker might consume, on average, 20 tonnes of fuel a day, 280 days a year. $2 charged on each tonne, and that’s $11,200 a year per ship. Extend this to the industry in the entire region, and the total figures could get very, very big.

Add that to the skyrocketing prices of bunker fuel itself, and we have a problem in two parts. Geopolitics and economics aside, the harsh reality is that a metric tonne of VLSFO from the Port of Fujairah, at the time of writing, costs around $850 — and it’s the charterers, who will be paying the bill when the levy comes into play.

|

Cooper ... leading Mideast maritime industries into a carbon-free future |

The solution? Technology. The few years between now and the IMRF’s eventual implementation offer a window of opportunity for forward-thinking shipowners and charterers to consider technologies and propulsion methods that will drastically reduce the fuel consumption and emissions of their existing vessels.

With hydrogen fuel and hybrid powertrains still years away from proper implementation, wind propulsion stands as one of the most attractive and current options for drastically reducing bunker input and carbon output on commercial fleets worldwide.

So, how far has the Middle East’s maritime industry progressed on the journey to decarbonisation, and where can it go next with the help of technology?

ROAD TO DECARBONISATION AND LESSONS

The aim of the IMO’s overall initial strategy is to reduce carbon emissions in international shipping by, at least, 40 per cent by 2030, pursuing efforts towards 70 per cent by 2050 (compared to 2008) with total annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to be reduced by, at least 50, per cent over the latter period.

Beginning in January 2019, ongoing data collection on fuel oil consumption by ships over 5,000 gross tonnes will inform a revision of the strategy in 2023, with the IMRF forming a key part of this.

There is little question that in the long run, IMRF is a win for the industry at large.

With more investment into developing nations’ maritime sectors, new trading routes, opportunities, and relationships will develop across international and intercontinental lines. It’s likely that some countries in the Middle East itself stand to benefit directly from the fund.

This is a positive outcome — but for many countries in the region, the commercial reality of the here and now needs addressing.

Fuel prices are already at an all-time high, and mandatory increases in costs per tonne are going to hit hard.

Authorities across the region are aware of this need for decarbonisation, though, as has been made clear by developments in the last few years.

Drydocks World is the largest centre in the Middle East for ship repair, conversion, newbuilds and MRO projects, with focus on renewables and energy-efficiency projects.

As a case study of one of the specialist shipyard’s successes, in December last year, it converted a soon-to-be-stranded Boskalis vessel into a crane vessel, BOKALIFT 2, for carrying out offshore operations, including offshore wind installation.

In another more recent example, this year we have seen support for the Global Ports Hydrogen Coalition from the UAE.

|

WindWings ... a solid-sail wind propulsion platform from BAR Tech |

The coalition is an initiative designed to enhance collaboration and dialogue between member nations on the adoption of low-carbon hydrogen fuel and technology in coastal industrial areas, feeding into the nation’s plans to be deriving three quarters of its power from clean sources by 2050. The initiative would promote the development of portside hydrogen storage and generation infrastructure, possibly to fuel hydrogen-powered ships.

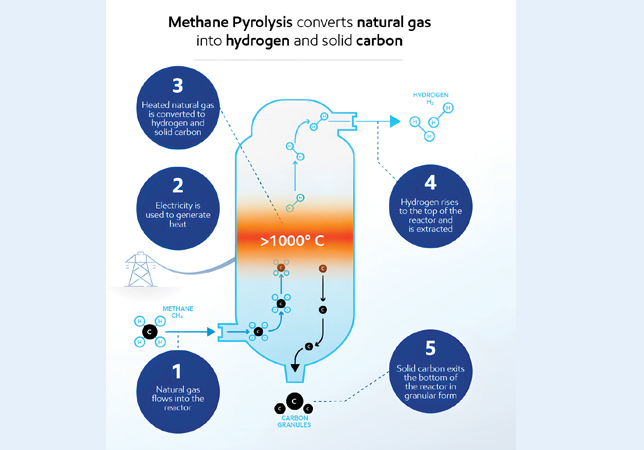

This is all good on paper, but hydrogen itself is far from maturing.

Hydrogen powertrains, while excellent for carbon reduction in concept, are yet to produce sustainable results from either a supply chain or developmental perspective.

The efficient procurement of hydrogen fuel is still the subject of extensive research, as are ship engines, which could use the fuel.

It’s unlikely that we will see this technology meaningfully deployed by the time the IMRF is implemented.

In cases like these, private entities need to step in for themselves when policy or research and development is slow, and no amount of waiting will help.

A governmental focus on cleaner fuels for the maritime industry is promising, but there are commercially available technologies, which are ready to be used today — solutions that individual companies can seize to immediately get ahead of the decarbonisation curve.

TECHNOLOGY’S ROLE IN ACCELERATING THE TRANSITION

As global attitudes and policy towards bunker reliance change, the fallout of additional financial responsibility for the Middle East’s shipping industry will remain under control as long as investment into decarbonising technology remains a priority.

Retrofitting fleets with such technology will effectively futureproof them from similar regulatory shifts.

One of the best solutions right now is wind propulsion.

On the one hand, the IMRF levy threatens the future and financial viability of the existing fleet.

Low-efficiency ships that burn more fuel will be subject to higher carbon taxes, making them less attractive for charterers and ultimately produce lower returns for investors.

Wind propulsion, on the other hand, harkens back to the roots of the maritime industry; an emissions-free resource, which just needs to be captured in the right way.

BAR Technologies is a simulation-driven marine engineering company, which develops world-class racing-inspired technology and applies it to sectors across the maritime industry, with a focus on solving sustainability challenges.

Having originally spun out from the former British America’s Cup Team, BAR Tech provides a wide range of design and engineering consultancy services.

WindWings, a solid-sail wind propulsion platform, is its answer to the call for decarbonisation in shipping.

With the capability to reduce fuel consumption by 30 per cent, WindWings can be retrofitted to an existing fleet to simultaneously dampen both the effects of fuel taxes and emissions.

Decarbonisation isn’t just good for the planet: it’s profitable. Whether mitigating the financial effects of international policy or simply reducing the amount that must be forked out on rapidly increasing fuel prices, it’s a long-term investment that yields immediate results.

There’s no better time than now for the maritime industries of the Middle East to take their first steps into a carbon-free future — without leaving any money on the table.

By Abdulaziz Khattak