Everingham ... CCUS focus

Everingham ... CCUS focus

While CCUS technology isn’t new globally, it is new to some Asian countries, and there is a need for creating clear regulatory and legal frameworks for it to reduce above-ground risk that might be a barrier to deployment, Paul Everingham, CEO of ANGEA, tells OGN

No matter where I travel in Asia, there are two energy-related conversations that inevitably come up.

The first is around energy security, which is understandable given the geopolitical landscape. Countries and industries seek assurance they will have access to reliable and affordable energy needed to continue driving economic growth.

The second centres on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). Again, it makes total sense.

Asia Pacific is going to have a massive increase in energy demand to 2050 and meeting that while also achieving climate objectives will require genuine energy transition.

As the ‘cleanest’ of the fossil fuels, natural gas is a perfect fit to underpin this, providing stable electricity generation that complements growing investment in renewables, while acting as a starting point for production of low emission fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia.

But there is also a need to manage the emissions profile associated with natural gas—in production, transport and use as a fuel or feedstock.

This is where CCUS enters the equation.

NO EASY NET-ZERO WITHOUT CCUS

|

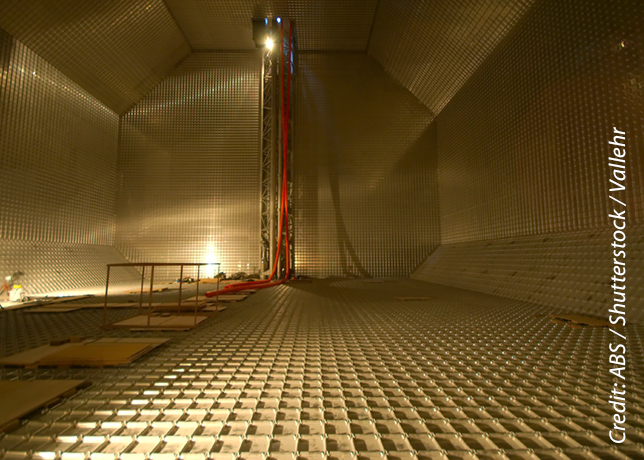

The Gorgon project started injecting CO2 in early August 2019 |

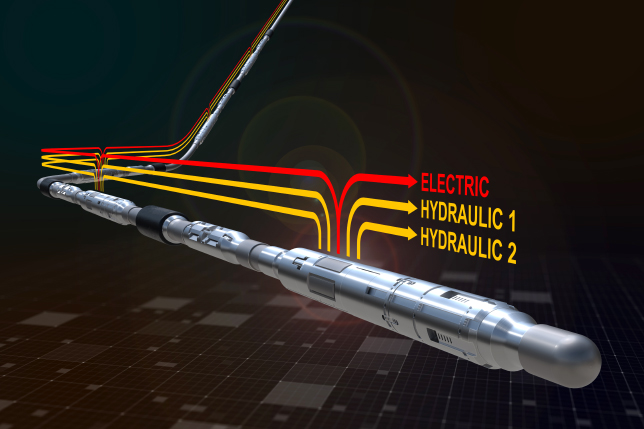

CCUS isn’t new technology. As a concept it’s been around for 80-plus years. In a more practical sense, the world’s first on-the-ground project emerged in the early 1970s.

What’s changed this decade is recognition that CCUS will be integral to the world meeting its climate targets. As the International Energy Agency (IEA) has made clear, there is no realistic pathway to net-zero that doesn’t involve massively increased investment in CCUS.

To me personally and for the member companies of the Asia Natural Gas and Energy Association (ANGEA) that’s an exciting scenario. There are challenges to be addressed but also opportunities to contribute to something that will change lives.

Successful energy transition in Asia will drive economic growth that can bring millions of people out of poverty.

As a region, Asia ticks a lot of boxes for CCUS.

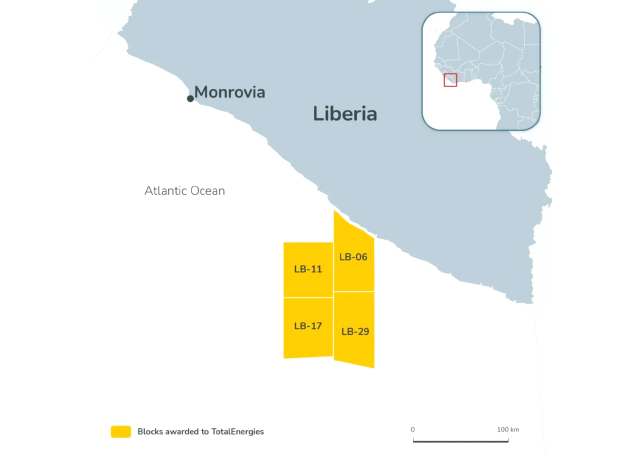

Geologically, there is storage potential in countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, while long-standing trading partner and neighbour Australia has proven capabilities.

Research suggests Southeast Asia could store up to 300 billion tonnes of CO2, with Australia having more than double that capacity – if only a percentage of it is feasible, it’s still significant.

Logistically, with transport a vital part of the storage picture, Asia is home to some of the most efficient shipping routes on the planet.

Politically, there are a wide range of Asian governments that are highly interested in CCUS, including Japan, Thailand, Singapore and Indonesia. Pleasingly, many have shown an appetite to collaborate across borders.

|

Gorgon project is the world’s biggest CCS facility |

The same is also true for industry in Asia. We’re already seeing situations where hard-to-abate sectors are engaging with stakeholders along their supply chains to develop mutually beneficial CCUS solutions.

Company-wise, the businesses undertaking research and development to meet Asia’s CCUS needs are global leaders in this technology. This includes ANGEA’s members: Chevron, JERA, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, JGC, LNG Japan, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Sumitomo Corporation and Woodside.

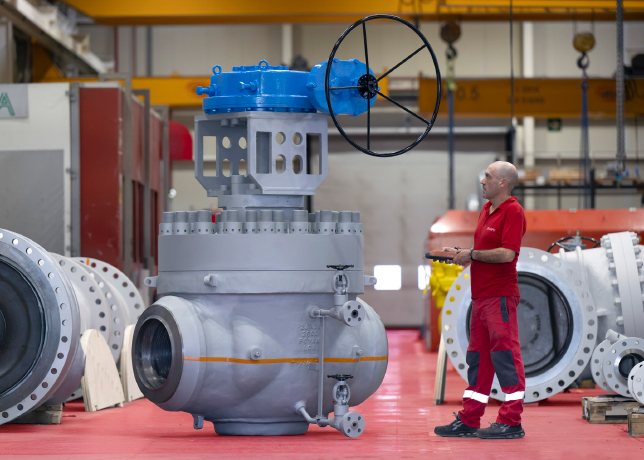

Meanwhile, finding an example of active CCUS in Asia Pacific simply requires a look to the south at Western Australia, where Chevron has been operating the world’s biggest carbon capture and storage facility at its Gorgon project since 2019.

So what must happen to facilitate widespread adoption of CCUS across Asia?

While CCUS technology isn’t new globally, it will be new to some of the countries in Asia in which it will be deployed – particularly at the scale required.

That means time and effort needs to be invested now in creating clear regulatory and legal frameworks for CCUS, to reduce above-ground risk that might be a barrier to deployment.

Given the necessity to ship CO2 and store it, policy must enable transportation across international borders.

Working with governments and industry on such frameworks is a key reason why ANGEA was formed in 2021.

Financially, institutions that have backed away from supporting new gas development need to acknowledge the importance of switching from coal to gas in Asia and reinstate support – both for future projects and the CCUS that will accompany them.

There are banks, which won’t countenance any form of hydrocarbon activity, reflecting an unfortunate disconnect in appreciation of the global gas supply chain and its importance to Asia meeting emissions targets.

There will, of course, need to be further advancements in technology, particularly in making CCUS as cost-effective as possible. But with the calibre of people and companies working on the task, I’ve no doubt strong and practical solutions will emerge.

From ANGEA’s perspective, at such a formative in Asia’s CCUS journey, we’re seeing green shoots right across the region.

Thailand has been one of the countries most receptive to CCUS, highlighted by a successful and well-attended Energy Transition Executive Forum, which ANGEA recently hosted in partnership with the Petroleum Institute of Thailand.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is working with Thailand’s largest power producer EGAT on CCUS as part of a suite of clean energy solutions, while there was news earlier in the year that Siam Cement would be testing CO2 capture with an aim to convert it to methane fuel.

Given cement-making is one of the hardest-to-abate sectors that’s highly encouraging.

Similarly, in Japan, we’ve seen an announcement in 2023 about ExxonMobil and Mitsubishi Corp collaborating on CCUS development with Nippon Steel for steelmaking, another industry with significant abatement issues.

Japan, with its established role for gas and renewables limitations, shapes as a leader in CCUS.

Chevron announced last year that it was studying the feasibility of transporting liquefied CO2 from Singapore to Australia and, more recently, unveiled a collaboration with Pertamina to explore carbon capture in Indonesia.

With an economy projected to grow to the world’s fourth-largest by 2050, Indonesia has a significant energy transition challenge ahead. It’s been pleasing to see recognition that gas and CCUS can be majors parts of the solution; ANGEA’s recent engagements with the Indonesian Government about this have been highly positive.

Exactly what the future will look like for CCUS in Asia is hard to pinpoint. It’s such a rapidly evolving area that almost anything feels possible.

However, one thing seems absolutely certain to me: over the next 20 years, CCUS will lose the novelty factor currently associated with it and become a part of our everyday lives.

* Paul Everingham is the inaugural CEO of the Asia Natural Gas and Energy Association (ANGEA), which works with governments, society and industry throughout Asia to build effective and integrated energy policies that meet each country’s climate objectives.