An oil refinery in Nigeria … Africa needs further investment in oil

An oil refinery in Nigeria … Africa needs further investment in oil

Africa has strong oil production growth potential, however, spending will be dominated by energy transition goals, more focus on gas and other factors, says Siva Prasad, Senior Analyst, Rystad Energy

Africa needs to overcome multiple hurdles, driven by costs, spending strategies and capabilities, financing and energy transition, to realise its energy production potential.

The continent on the whole currently holds over 77 billion barrels of oil equivalent of liquids and produces just over 7 million barrels per day (mbpd), about 16 per cent lower than pre-pandemic levels of 8.3 mbpd.

Output is expected to decline further to 6.75 mbpd in 2025, and to 5.9 mbpd in 2030.

However, there is potential for reversing the declining trend and bringing overall liquids production above pre-pandemic levels.

Some 70 per cent of Africa’s reserves are owned by the respective national oil companies (NOCs) and oil majors according to a report by Rystad Energy evaluation of African oil markets in 2023 and the next few years.

The potential spending is dominated by NOCs and majors, with 2023 cumulative spending estimated to be 60 per cent of the overall capex spent on developing liquids in Africa.

This share of spending is expected to stay at or higher than 65 per cent of the total annual spending over the period 2024-2035.

The overall capex spending on liquids over 2023-2035 is estimated at just over $500 billion, with NOCs and majors accounting for about 65 per cent of this. This leads to issues with the spending capabilities of NOCs and spending choices of majors.

Larger Sub-Saharan African NOCs like Nigeria’s Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) and Angola’s Sonangol have historically failed to meet their working interest share of upstream investments, leading to Modified Carry Agreements (MCAs) in Nigeria and partial stakes in Sonangol in Angola.

The other issue that is a future problem is the spending choices of oil majors. Oil majors are increasingly focusing on cutting down upstream exposure and spending to reduce carbon emissions, particularly in Africa. This aligns with Africa’s pledge to use gas as a transition fuel at last year’s COP 27.

The business environment also plays a crucial role in these majors’ decisions to continue or discontinue their upstream operations, as they divide their core and non-core areas.

Several projects, including delayed mega deepwater discoveries, NNPC onshore swamp fields, upcoming start-ups offshore Angola, Pecan-Nyankom fields offshore Ghana, offshore volumes off Namibia and Cote d’Ivoire, and the delayed South Lokichar project onshore Kenya, are currently deemed uncommercial due to higher breakeven prices than the projected oil price forecast.

The projects are projected to pump liquids, primarily oil, to Africa’s production volumes of 30,000 bpd by 2025, 120,000 bpd by 2027, 1.32 mbpd by 2030, and 3.7 mbpd by 2035, with the potential to reverse Africa’s production by 2030, with an overall output of 7.2 mbpd and over 8.5 mbpd by 2035.

Namibia has become a significant oil producer, with multiple discoveries bringing recoverable reserves to over a billion barrels.

Nigeria’s tax reforms, transforming the Petroleum Industry Bill into the Petroleum Industry Act, have led to the signing of new production sharing contracts (PSCs) by major oil companies like ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies, and Eni. These contracts are expected to unlock over 10 billion barrels of oil and generate over $500 billion in revenue for the government and PSC partners.

Angola’s Agencia Nacional de Petroleo, Gase Biocombustiveis implemented marginal field incentives, resulting in oil majors receiving tax incentives for delayed deepwater developments. Also, Eni has fast-tracked its Baleine project offshore Cote d’Ivoire, bringing the first phase online.

Although these positive indicators suggest a future for Africa’s oil output, they also suggest a dependency on delayed or new developments that require significant greenfield spending.

ESTIMATED TIMELINE SPENDINGS

The estimated timeline and required greenfield spending for projects to drive additional supply and reverse production decline in Africa is expected to result in a potential capex of almost $41.5 billion and increase further to nearly $44 billion.

The cumulative potential upstream greenfield plus brownfield spending over the period 2023-2030 is estimated to reach almost $450 billion, with an average annual spending of over $56 billion.

The total potential upstream spending over 2031-2035 can be $375 billion or an average annual spending of $75 billion.

The cumulative actual upstream spending over the periods 2023-2025, 2023-2030, and 2031-2035 is much lower, at $120 billion, $290 billion, and $123 billion, respectively, While the overall estimated actual spending over 2023-2035 is about $410 billion, double the potential spending.

The estimated total spending needs to be double the estimated economically viable spending over the period for the declining oil and gas production trends to reverse.

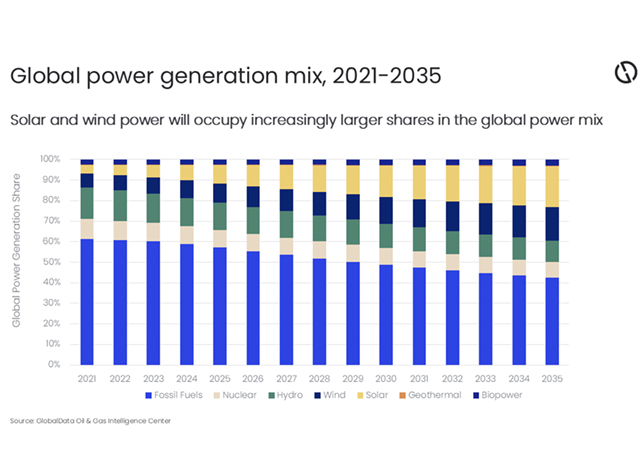

CLIMATE SCENARIOS & TRANSITION TO REDUCE SPENDING ESTIMATES

Climate scenarios and energy transition risks take the spending estimates even lower over the period. Rystad Energy estimates Africa’s 2023 – 2035 upstream spending in a "Mean" scenario is close to the actual economically viable spending.

Rystad Energy’s 'Mean' scenario predicts a long-term oil demand trajectory of 107 million bpd in 2026 and a gradual decline to 66 million bpd by 2050, aiming to cap global warming at 1.9 deg C, and estimating a cumulative spending of $370 billion over 2023-2035.

In addition, the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) scenario from the International Energy Agency (IEA) aims for the global energy sector to achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

This scenario is a backward calculation from the 1.5 deg C goal, with Africa’s cumulative upstream spending estimated at $270 billion, or 66 per cent of actual spending.

However, the mean and NZE scenario spending estimates are only 45 per cent and 33 per cent of potential spending, respectively.

Also, European financial institutions have seen a negative compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in fossil fuel financing and have progressively shifted their climate policies away from fossil fuels.

Asian financial institutions have maintained a steady CAGR in fossil fuel financing, with their climate policies either remaining undefined or unchanged.

In recent months, BNP Paribas, Europe’s largest oil and gas lender, announced it will no longer finance new upstream developments, aiming to reduce its upstream exploration and production exposure by 80 per cent by 2030 and align its credit portfolio with net-zero climate targets.

Singapore’s Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC) also announced it will not finance any upstream projects approved for development after 2021, targeting a 95 per cent and 55 per cent reduction in absolute emissions from the oil and gas and power sectors respectively by 2030 and 100 per cent by 2040.

Between 2023 and 2035, about 50 per cent of the actual spending and 72 per cent of the potential upstream spending in Africa are expected to be greenfield spends, or spending on newer developments.

These moves by banks could be significant blows to the global oil and gas sector, particularly in Africa, which already faces a relatively unsafe business environment compared to other regions.

In conclusion, the African oil market faces challenges such as costs, spending strategies, financing, and energy transition to fully recover its potential.