The haype around hydrogen-ready turbines needs to be evaluated

The haype around hydrogen-ready turbines needs to be evaluated

Recent trends show a surge in "hydrogen-ready" and "hydrogen-capable" claims from electric utilities and project developers, but experts caution that these assertions may be little more than marketing hype.

According to a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), US state regulators and investors need to carefully examine the feasibility and implications of these claims.

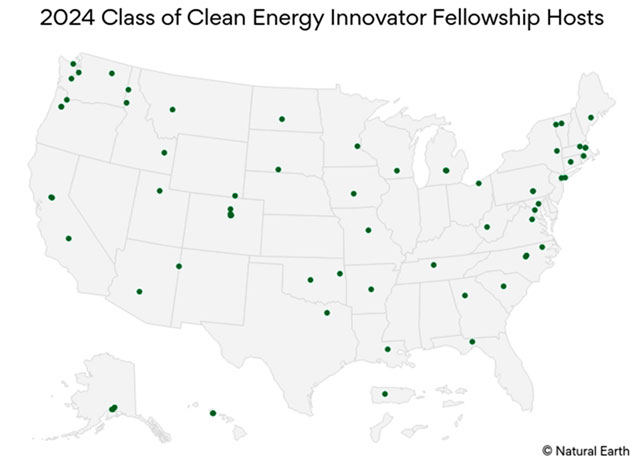

Utilities across 18 states have announced plans for new methane gas-fired power plants that they describe as "hydrogen-ready".

These projects, ranging from technology demonstrations to large-scale commercial developments, are often presented as environmentally friendly advancements.

However, the IEEFA report argues that these projects will predominantly operate on methane for, at least, the next decade, with hydrogen use remaining minimal or non-existent until 2035 or later.

For instance, Duke Energy’s proposed projects, totaling 2,260 megawatts (MW) of capacity, plan to introduce hydrogen at a negligible 1 per cent blend by 2035.

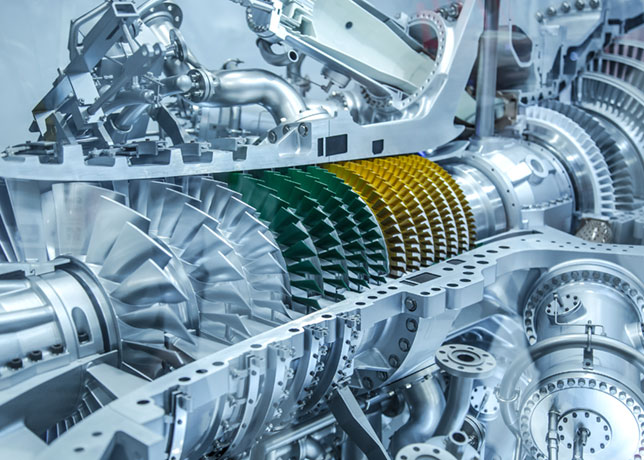

The report highlights three major hurdles that could impede the widespread adoption of hydrogen in gas-fired turbines.

First, the US currently produces around 10 million tons of hydrogen annually, mostly for the petrochemical and fertiliser industries.

Significantly scaling up hydrogen production to meet power sector demands would require a substantial increase in production capacity, which is not anticipated in the near term.

Second, the infrastructure for transporting hydrogen is insufficient. Extensive new pipeline networks would be needed to deliver hydrogen to power plants, a costly and complex endeavor.

Additionally, the current storage infrastructure for methane, including extensive underground facilities, does not have a comparable counterpart for hydrogen. Building such infrastructure poses significant challenges and safety concerns.

Third, while hydrogen can reduce carbon dioxide emissions when blended with methane, the environmental benefits at low blending levels are marginal.

The infrastructure costs for hydrogen blending could outweigh these benefits. Furthermore, hydrogen combustion generates nitrogen oxides, which can exacerbate local air pollution unless controlled with expensive technology.

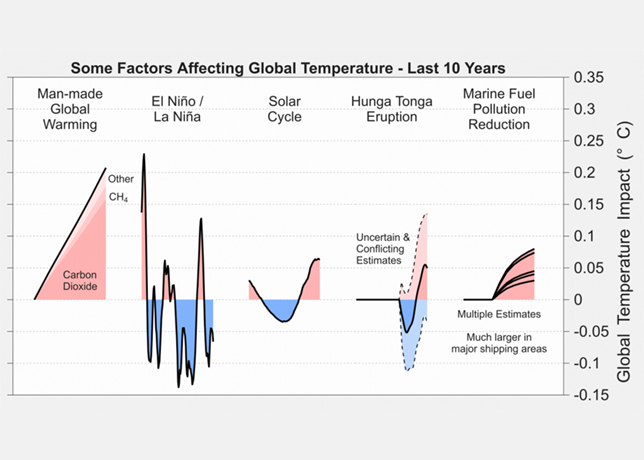

The IEEFA report also points out that hydrogen's indirect impact on climate change could be substantial. Hydrogen’s global warming potential is significantly higher than that of methane when considering its effects on other gases.

In light of these issues, the report makes several recommendations for regulators and financial stakeholders.

Utilities should bear the costs associated with developing hydrogen-ready turbines rather than passing them on to consumers.

Full transparency regarding the costs of hydrogen infrastructure, including pipeline construction and fuel sourcing, is essential.

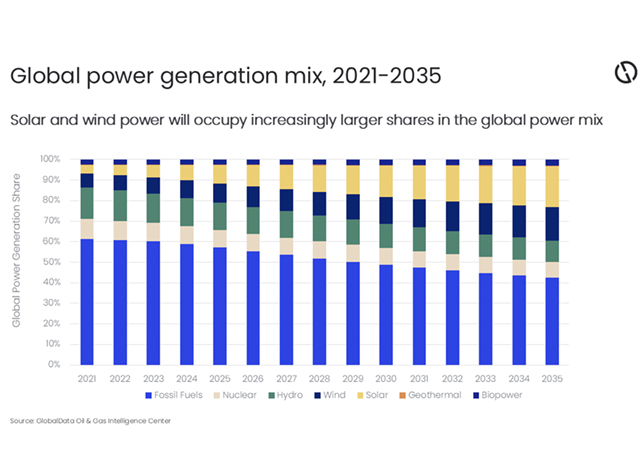

Regulators should also ensure that a comprehensive analysis compares hydrogen plans with zero-carbon alternatives such as wind, solar, and battery storage.

For investors, the report suggests that current funding for methane-fired power plants should be scrutinised carefully, given the long-term uncertainties and potential environmental costs associated with hydrogen integration.

As the energy sector continues to explore hydrogen as a potential fuel source, the IEEFA’s findings underscore the importance of rigorous evaluation and transparent communication to avoid costly investments in unproven technologies.