Costs of the flagship project have risen sharply

Costs of the flagship project have risen sharply

ANGOLA’S liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant faces major reconstruction to fix design flaws and corrosion of nearly-new equipment, threatening to extend a lengthy closure and pushing unofficial estimates of the project’s cost to at least $12 billion.

US oil group Chevron, Angola LNG’s biggest shareholder, acknowledged design problems with the export project which began production last year but shut down this April after a series of fires, leaks and mechanical troubles.

A consortium of investors, which apart from Chevron includes Angolan state energy firm Sonangol, BP, Total and Eni, contracted US engineering giant Bechtel to build the technically advanced plant on the Atlantic coast 300 km (180 miles) north of Luanda.

Chevron CEO John Watson declines to single out anyone for blame. “I don’t point fingers. This is our responsibility. It’s a partnership consortium. The partnership consortium chose the contractor. We’ve run into some design issues. We’re working to correct them,” he tells Reuters.

Watson gave no details of the project’s problems, which have included two fires, a major pipe rupture and gas leak, plus the capsizing of an offshore rig last year in which one worker died.

Costs of the flagship project have risen sharply since Angola LNG made an original estimate of $4 to $5 billion eight years ago. In 2009, Chevron put the figure at $10 billion.

One project source told Reuters that the cost of delays and repairs alone have reached $4 billion since 2010, pushing the overall price to between $12 and $14 billion.

Bechtel, maker of a third of all the world’s LNG plants, did not respond to Reuters requests for comment. Apart from Chevron, the consortium members declined to comment.

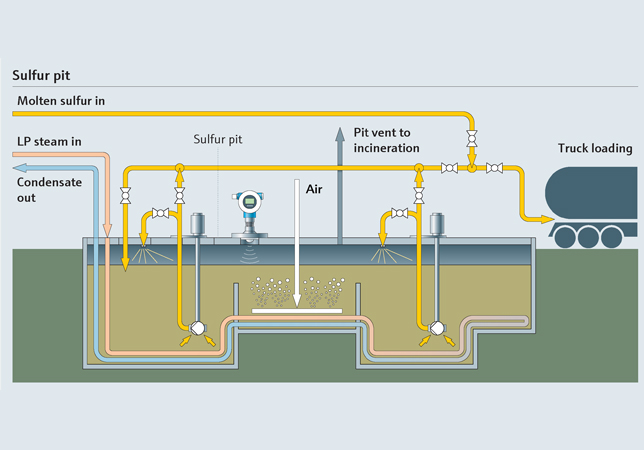

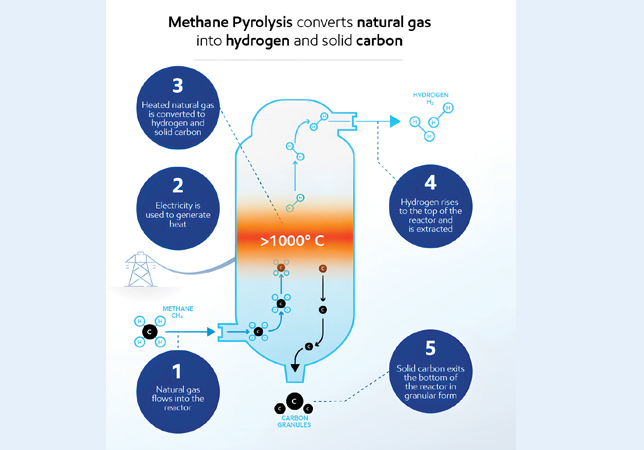

LNG plants, which turn natural gas into liquid for shipment by sea to distant markets, use some of the most intricate and expensive machinery in the energy industry. They often suffer glitches and require annual maintenance but even so, Angola LNG’s problems stand out.

The LNG facility, which processes gas from offshore fields, was greeted as a triumph when it started up in June 2013. The southern African country, the continent’s second biggest crude oil exporter, was at last to become a major supplier in the world’s fastest-growing energy market, promising to help it recover from almost three decades of civil war.

A little more than a year on, it has exported only 10 cargoes, whereas a project of its size would typically produce about 66 shipments annually.

CALCULATING THE COST

Three sources involved in Angola LNG, who declined to be named because they are not authorised to speak publicly, say about a third of the plant needed rebuilding.

Industry expert Liane Smith, who does not work on the project, calculated for Reuters the rough cost of reconstruction on such a scale.

“Normally I work on the figure that the materials element of a plant is about 40 per cent of the cost of a project,” says Smith, managing director of WG Intetech, a division of British firm Wood Group which ensures the quality of oil and gas wells. “So that would take you to about $1-2 billion as a rough estimate on how much replacing a third of the plant could cost,” he adds.

Officially, the Angola LNG plant will remain closed until mid next year. However, the project sources said this could slip into 2016, depending on the scale of the rebuilding work.

Corroded pipelines are already being repaired or replaced and valves will also need renewing, while compressors that are prone to uncontrolled surges of gas pressure will have to be overhauled. These compressors pump the gas through cooling units to liquefy it at -164 C (-263 Fahrenheit).

Investors in such a plant would typically expect it to operate for more than 30 years. At Angola LNG, equipment is rapidly deteriorating due to salt winds blowing off the Atlantic. “As a result it already looks like a 20-year-old plant,” a source who oversaw construction said.

|

Angola LNG ... major reconstruction required |

In less than a year of operations, the plant’s carbon steel pipes, LNG storage tanks and compressors have lost an average 2 millimetres from their thickness due to corrosion, one of the project’s inspectors told Reuters.

An Angola LNG spokesman says he had no information to suggest Bechtel used anything but the most appropriate materials and equipment. “Angola LNG’s primary responsibility remains safety of the plant and its people; and addressing issues to ensure that the plant can restart and ramp up,” the spokesman says.

Pipelines that lose 3 millimetres or more need repair or replacement, the project inspector says. Tests to check the thickness of all equipment are underway.

“The plant is built with sub-standard materials. It’s a poor design using poor construction material,” a second inspector says. Other workers involved in the project among the dozen who spoke to Reuters echoed his appraisal.

Smith at WG Intetech says stainless steel used in LNG plants is usually low grade because the gas itself is not corrosive. But she adds: “Such a basic stainless steel is not resistant to salt spray or seawater in a hot climate, so it needs particular care during fabrication and commissioning.”

EMERGENCY VALVE FAILURE

The plant has suffered problems in dealing with varying grades of gas which arrive by pipeline from the offshore fields containing liquids. Surging liquid petroleum mixed with the gas badly damaged a section of pipe in late 2012 and delayed the start of operations by eight months. Even when it did get going, the problem kept output below 50 per cent of capacity last year.

Production halted indefinitely in April this year due to a pressure blast in a line which flares off excess gas. Large volumes of gas spewed out and the sources said only luck prevented ignition and a full-scale explosion.

“This time it was (a) mis-operations problem and a total malfunction of the emergency pressure relief valves in short,” says one source.

New equipment is being shipped in to help handle and to strip the liquids from the gas, two sources say.