The ME-TECH in session

The ME-TECH in session

Refined products constitute a mature market where the opportunities for growth are mostly limited to the mobility needs of a rising middle class in emerging economies

Crude-oil-to-chemicals (COTC) technologies might be the next development step for refiners faced with diminishing returns on the production of petroleum products.

"COTC represents the ultimate integration stream", panel experts said at the ME-TECH 2019 conference in Abu Dhabi.

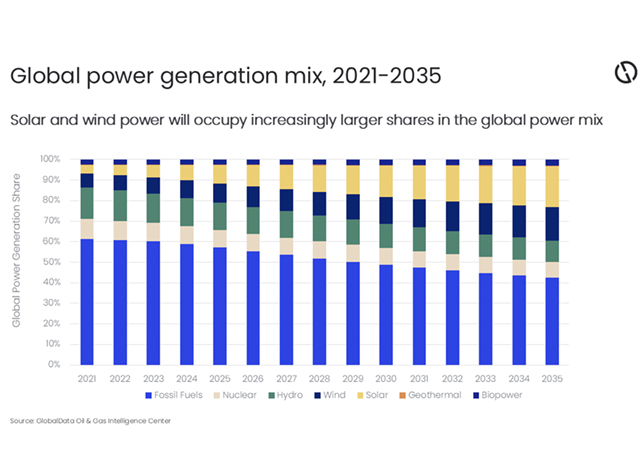

Refined products constitute a mature market where the opportunities for growth are mostly limited to the mobility needs of a rising middle class in emerging economies. Consensus estimates for the cumulative growth in refined fuels until 2030 stand at 0.6 per cent.

The main threat comes from electric vehicles and improvement in fuel efficiency, even if non-OECD countries will still remain an important source of fuel demand in the medium-term, in particular in the Asia-Pacific region.

However, this exception confirms the rule. Combined with unprecedented swings in crude oil prices and lower refining crack spreads across the board, refineries have been struggling for value growth. It is, therefore, no surprise if some of them are increasingly considering integration with petrochemicals production to supply a fast-growing market with higher-value products.

When the development of the petrochemical industry took off after the Second World War, driven by the growing use of plastics, some refiners saw the opportunity to supply these new markets, but the synergies between the refining and the petrochemical industries were essentially lacking. Since then, the refinery/chemicals interface has been considered with limited success.

Refiners have instead earned most of their profit from selling road transport fuels such as gasoline and diesel. Prices for petrochemical feedstock – since then forecast as one of the main sources of demand growth until 2050 – often trended lower than crude oil prices.

In Europe, the expansion of diesel as the main road transport fuel produced an excess of naphtha, which became available for making petrochemicals (about 30 per cent of naphtha in Europe comes from the refinery stream).

In the US, naphtha is needed to make gasoline, still the dominant road, but ethane from shale oil and gas is now available in increasingly larger volumes and at a cheap supply cost for steam cracking. In the Middle East, significant volumes of gas co-produced with crude oil were flared off until it was decided to develop a petrochemical industry to produce higher-value streams from the cheap and ample domestic supply of ethane.

The 26-unit Sadara petrochemical plant, a $20 billion joint-venture (JV) between Saudi Aramco and Dow Chemical, can produce 1.5 million tonnes of ethylene per year from local, cheap ethane feed from Aramco (alongside LPG and naphtha in the kingdom’s first mixed feed cracker), in addition to about 30 other chemicals.

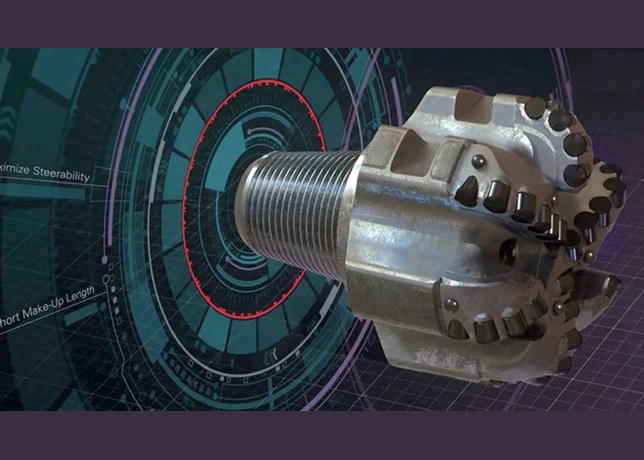

The production of chemicals such as olefins and aromatics directly from crude oil – as opposed to the steam cracking of ethane and/or naphtha or via traditional reforming, has found new momentum.

The current imbalance between a slower demand for motor fuels (gasoline, diesel) and the rapid growth in markets for petrochemicals like olefins (ethylene, propylene), aromatics (BTX) and specialty intermediate streams like C4s has given integration projects new life.

The product imbalance has made the idea of using crude as a direct feedstock particularly appealing to integrated producers (mostly large international oil companies – IOCs), but also to large chemical companies.

With limited long-term growth perspective for motor fuels, many refiners will find it increasingly difficult to compensate for the reduction in road transport fuels sales. The regain of interest in petrochemical integration reflects a desire to hedge against this risk or simply survive lower margins by diversifying revenue streams.

The mismatch between refinery configurations and product demand should, in theory, give refiners an incentive to deepen integration with petrochemical plants and boost the production of high-value products down the processing chain.