The complex carbon market needs an in-depth definition of carbon credit quality

The complex carbon market needs an in-depth definition of carbon credit quality

A fundamental issue for the carbon market is a lack of a universally accepted and in-depth definition of carbon credit quality, says a report by Carbon Market Watch

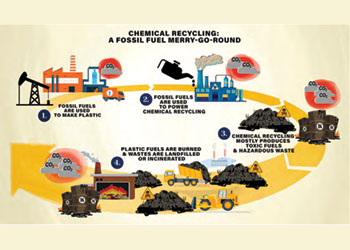

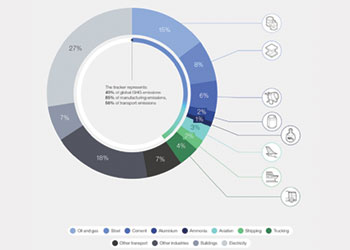

An overwhelming majority of projects rated by some carbon credit rating agencies fail to deliver a credible score, while the majority of credits circulating in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) do not live up to their promised impact, says an expert on global carbon market.

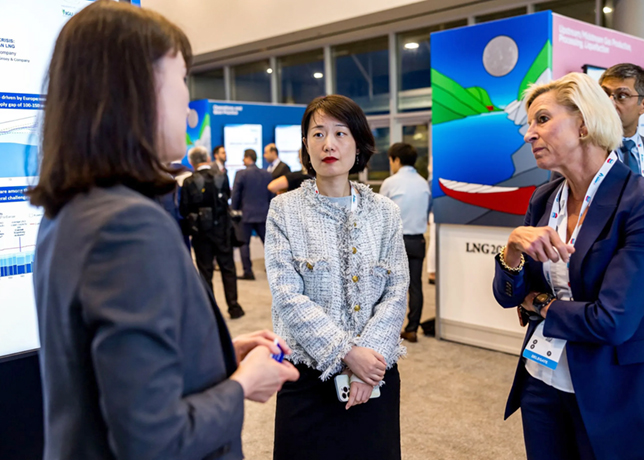

Benja Faecks says this in a report she penned for Carbon Market Watch (CMW), an independent watchdog in carbon pricing and research organisation and in replies to questions by OGN energy magazine.

The report commissioned by CMW and conducted by Perspectives Climate assesses the performance of four major carbon credit rating agencies – BeZero, Calyx Global, Sylvera and Renoster – and highlights discrepancies among the agencies' assessments.

It did this by evaluating approaches to additionality (does the project bring additional climate benefits that would not have occurred otherwise?); non-permanence risks (how likely is carbon storage to be temporary or reversed?); leakage risks (how likely are destructive activities to shift elsewhere?); and co-benefits and safeguards.

KEY FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS

The report found the lack of a universally accepted and in-depth definition of carbon credit quality as a fundamental issue for the carbon market.

The carbon credit rating agencies assessed in the report aim to address this lack of standardisation by distinguishing between robust carbon credits and those not delivering on their promises. The agencies claim to increase transparency, mitigate reputational risk and enable fair pricing.

Amongst the agencies, Renoster’s approach differs the most from the others in that the company aims to limit its qualitative assessment and instead derive its ratings as much as possible based on an algorithmic analysis. Further, Renoster assesses leakage but excludes it from their overall rating score.

Approaches to rate carbon credits differ in many ways across the agencies. For example, most agencies use direct tests for their assessments, while Renoster’s tests are mostly implicit.

Other key differences identified include approaches to limit the overall score of a project based on its additionality score.

This is done differently across agencies. Other examples include the assessment of double-issuance and double counting, co-benefits and safeguards, leakage, buffer strength, permanence benchmarks and rating transparency.

According to the findings, Calyx has the most stringent cross-sectoral as well as REDD (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) approach.

One of the lessons learned from the report is that rating agencies assess the likelihood that a carbon credit truly represents a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) that has been reduced or removed by a project.

Any classification less than the maximum score indicates that a project is likely not delivering the equivalent of one ton of CO2e emissions reduction or removal per credit issued.

Faecks says: "More than 99 per cent of all projects rated by the rating agencies in the timeframe we looked at it don't score the maximum score. Buyers should, therefore, not use carbon credits to offset or compensate for their emissions because the numbers don't add up."

She says that under a contribution model, understanding the quality of a carbon credit becomes much more meaningful.

"Once it is acknowledged that credits cannot be fully equivalent to a reduction of 1 ton CO2e, it becomes very important for buyers to understand what are the strengths and weaknesses of a given project, and its associated credits."

The report states that agencies can sometimes struggle with the lack of project documentation which hampers the full assessment of the project.

THE RISE OF RATING AGENCIES IN CARBON CREDITS EVALUATION

"The carbon market is complex and opaque, and has had some (rightfully) negative media attention," says Faecks.

Amidst this, carbon credit rating agencies have emerged to navigate buyers through the jungle of carbon credits on the market right now.

They are supposed to play a valuable role in assessing the quality of credits in the voluntary carbon market (VCM).

And while rating agencies do not award carbon credits to projects, they have emerged as assessors independently evaluating the likelihood of whether or not a credit generated by a certified project is truly representative of a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) reduction or removal.

More often than not rating agencies attribute medium to low scores to projects, demonstrating the scrupulous quality of their evaluations relative to the liberal approval of the carbon crediting standards.

Faecks says some buyers and intermediaries attempt their own due diligence by scrutinising project details and methodologies. However, this process has proved very costly and complex.

"To address these concerns, carbon credit rating agencies emerged as organisations striving to assess and rate the quality of carbon credits in the VCM. These agencies have developed and use their own assessment frameworks to provide a more comprehensive and impartial evaluation of carbon credits," she explains.

"The fact that so few credits receive the highest score from rating agencies proves that the idea that emissions can be offset or compensated for using carbon credits is an illusion," explains Faecks.

"This makes them unsuitable to offset emissions."

However, there is no uniform, aligned approach taken by the rating agencies and the variety of end results has led to a confused marketplace.

With agencies using different grading scales, a given grade - for example, ‘B’ - can imply significantly different levels of quality depending on the agency that is assigning it.

While such a rating might be taken at face value as being the second best result, for some agencies it is actually only the sixth best.

CONCLUSION

"Rating agencies can be the agents of change in a world that moves away from compensation and offsetting towards less absolute claims of climate contributions," says Faecks. "This opens the door to more transparent and honest communication about the different impacts that carbon credits truly represent."

She says there are other organisations that are making efforts to enhance credit quality, like the ICVCM.

"Recent developments in the VCM show that rating agencies are not the only organisations taking an interest in determining carbon credit quality. The IC-VCM, in setting a minimum bar for carbon credit quality, has effectively established a sort of rating as well, albeit a binary one," she concludes.

By Abdulaziz Khattak