An overview of key issues affecting workplace safety and health

An overview of key issues affecting workplace safety and health

Workplaces are safer than before, but new threats are emerging, not from machinery or toxic gases, but from disillusioned employees, algorithmic decisions, and neglected investment in safety infrastructure

In today’s increasingly interconnected workplace, physical safety alone no longer suffices; health and safety at work now hinges equally on mental resilience, trusted leadership, emerging technologies, and genuine sustainability commitments.

As organisations and regulators recalibrate for these new realities, several emerging risk areas demand integrated responses across industries globally.

The insights stem from the Drager Safety and Health at Work Report 2025, conducted for Drager Safety UK and carried out independently, which surveyed diverse workforces on safety perceptions and emerging hazards.

One striking finding reveals that while most report feeling physically safe, a majority feel psychological, technological, or financial pressures are eroding actual safety margins.

In fact, while 96 per cent of people feel physically safe at work, 65 per cent believe a lack of psychological safety is contributing to physical safety risks.

"Despite the vast majority of people reporting that they do feel safe in their workplace, there are clear areas of dissatisfaction and cynicism across key areas which need addressing to prevent negative sentiment developing further," says Matthew Bedford, Managing Director, Dräger Safety UK.

|

Matthew Bedford |

He adds: "It is vital that we do not allow complacency to develop in relation to workplace health and safety, and that instead, innovation and new approaches being see in the fields of safety training and safety technology are leveraged fully to keep workplaces safe despite the challenges faced."

At the core of this evolving landscape is psychological safety; the employees’ ability to speak up, share concerns, or report mistakes without fear.

A growing cohort of employees—dubbed ‘Gen C’ or Generation Cynical—has emerged, marked not by age but by disillusionment.

These are workers who feel disengaged from their employers’ safety promises, sceptical of new initiatives, and doubtful about whether leadership is truly prioritising their wellbeing.

Many feel that despite the language of care, they are left to shoulder more of the safety burden than ever before.

However, a majority of workers (63 per cent) now feel that too much responsibility is placed on employees compared to employers when it comes to workplace safety and wellbeing.

This sense of imbalance is a defining trait of Gen C, who increasingly see workplace safety as an individual burden rather than a shared organisational priority.

Global data confirms its importance. The Workplace Options Psychological Safety Study found stress, conflict and performance pressure dominating in nearly every country surveyed, revealing burnout among young adults and overwhelming pressure to conform.

Leaders now view psychological safety not as a perk but a critical business necessity.

Research further shows poor psychosocial safety climate triples new depressive symptoms, reduces engagement and increases absenteeism and presenteeism.

Notably, mental health and wellbeing—ranked the top concern in 2024 by 82 per cent of respondents—dropped to third place in 2025, with traditional safety risks like fire and respiratory hazards ranking 10 percentage points higher.

This drop in perceived importance fuels Gen C’s mistrust in how seriously companies value psychological wellbeing.

Closely tied to mental resilience are financial pressures. Economic slowdowns, cost cutting and wage stagnation limit budgets for safety upgrades, wellness programmes and training.

For Gen C workers, outdated gear isn’t just a physical hazard, it’s symbolic of deeper neglect and unfulfilled safety commitments.

Globally, workplace mental health crises have intensified: Depression and anxiety now cost the global economy around $1 trillion annually and more than 12 billion working days are lost each year.

Investors and stakeholders are pressing firms to treat mental health with the same rigour as financial reporting, warning that poor support can erode productivity and brand value.

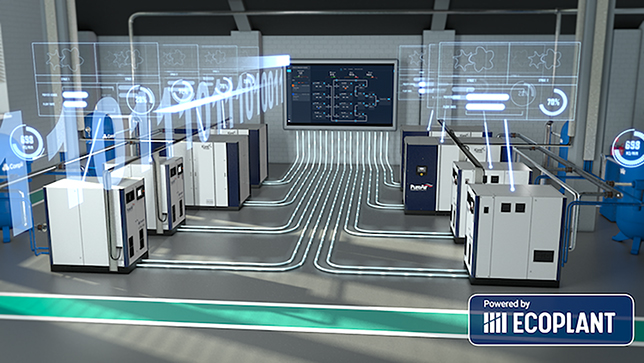

Artificial intelligence (AI) presents a mixed blessing. While AI-powered systems can automate hazardous tasks, support predictive maintenance and deliver immersive training, misuse and lack of governance create new hazards.

While 44 per cent of workers say AI could help reduce human error by automating repetitive safety checks, a striking 92 per cent also acknowledge potential risks from its use in workplace safety.

Over-reliance on AI was the top concern for 47 per cent of respondents.

Among Gen C, AI is viewed with particular caution. They see it as a potential shortcut that may mask real gaps in accountability and judgement.

Surveys show many workers conceal AI use (57 per cent), with only 47 per cent having any formal training and a majority failing to verify outputs for accuracy.

The ILO and PEROSH emphasise that AI adoption must be accompanied by risk assessments, human centred design and robust oversight; otherwise gains may be undermined by algorithmic errors or loss of human judgement.

Yet all the technology in the world is ineffective without high quality safety training.

Some 73 per cent of workers see safety training as just a ‘tick-box’ exercise, and nearly 1 in 10 (9 per cent) say they’ve received no safety training in the past five years. This contributes to the Gen C sentiment that training is performative, not purposeful.

Global trends mirror that: Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace report shows only a third of employees feel they are thriving, while engagement and well being are declining, pointing to deficits in development and support systems.

Organisations investing in experiential, role based training and peer mentoring report stronger retention and safer work practices.

Outdated equipment remains a serious concern. Across sectors, expired or neglected machinery poses avoidable hazards.

Even where funds may exist, organisations often defer replacement due to cost pressures.

The Drager report also highlights financial constraints as a root cause of equipment neglect, echoed by two-thirds (66 per cent) of employees who rate their equipment as inadequate or outdated.

The World Day for Safety and Health at Work 2025 report notes that digitalisation and AI should reduce reliance on ageing gear, but only if investments are made proactively.

When equipment fails, it not only physically endangers workers but also erodes trust in broader safety systems.

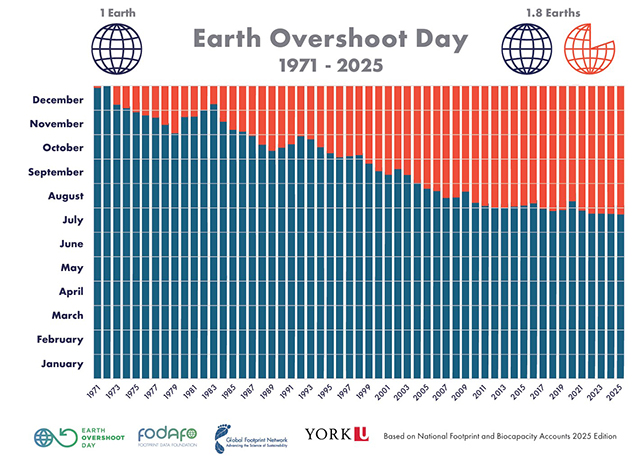

Finally, greenwashing undermines genuine progress. When companies overstate sustainability achievements, particularly in safety-related environmental initiatives, employees grow sceptical.

A growing body of research in corporate communications studies shows automated detection tools revealing misleading language is increasingly common; but the underlying issue remains one of trust and transparency.

Without credibility in environmental safety, workers become cynical, damaging morale and engagement. These six problems are not isolated; they feed on one another in complex ways.

Stress from financial insecurity can compromise psychological safety, while poor training makes AI misuse more likely; outdated equipment raises physical risk, compounding mental fatigue; and greenwashing amplifies distrust in leadership, stifling open reporting of concerns.

Only a holistic approach that treats mental, physical and environmental safety as parts of a unified culture can begin to counter the risks.

From insights within various global findings, a clear imperative emerges: Leaders must integrate well designed training, upgrade infrastructure, govern AI ethically, and communicate honest sustainability efforts. And all of these are underpinned by strong psychosocial safety climates.

Embedding these into strategy, rather than policy alone, shifts safety from compliance to accountability and trust.

As global organisations adapt to a future shaped by automation, inflation and social change, workplace health and safety must be reframed as dynamic, interrelated and culture driven.

The path forward lies in leadership that listens, adapts and invests, not just in protocols, but in people.