Gas flaring wastes a vital resource that could power schools, hospitals, and industries

Gas flaring wastes a vital resource that could power schools, hospitals, and industries

While countries like Nigeria and Mexico continue to burn billions in wasted energy, worsening climate impacts, Gulf nations are capturing flare gas for domestic use and exports

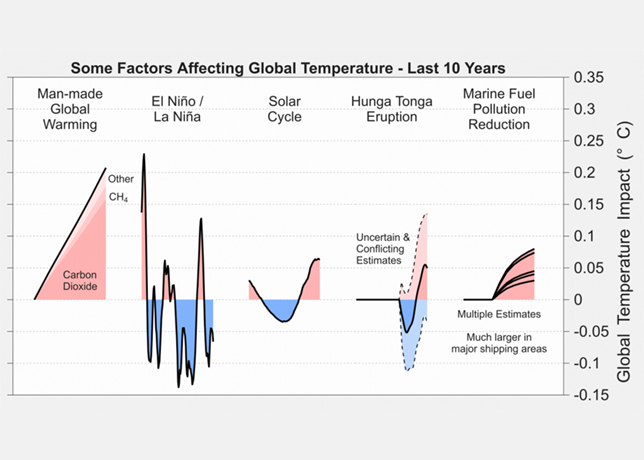

In the crucible of the global energy system, the burning of associated gas during oil extraction remains a glaring paradox, wasting a valuable fuel while contributing heavily to greenhouse emissions.

In 2025, the issue has become more urgent than ever as flaring volumes soared to levels unseen since 2007.

Yet some regions, notably the Arabian Gulf, are quietly adopting practices that could chart a greener path forward.

According to the report Global Gas Flaring in 2024, around 151 billion cu m of gas were flared globally in 2024, marking the highest annual volume since 2007, and releasing an estimated 389 million tonnes CO2-equivalent emissions, including significant unburnt methane.

The gas flared—almost equal to the annual consumption of the entire African continent—also represents a financial waste exceeding $60 billion if sold at EU market prices.

FLARE TRENDS ACROSS OIL-PRODUCING NATIONS

Nigeria remains among the countries with high flaring volumes. Flaring in the country rose 12 per cent in 2024 for the second consecutive year, driven largely by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) and smaller indigenous firms that have taken over divested assets from international majors.

These operators are frequently undercapitalised or lack technical expertise for gas recovery and processing.

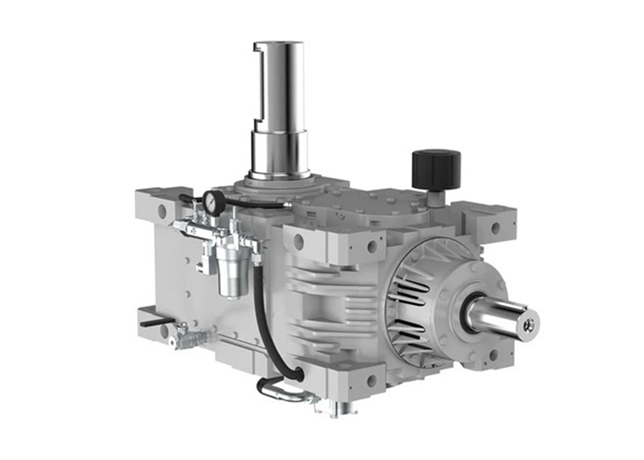

|

Adnoc is using the latest technology to capture CO2 for injection |

This results in gas being burned rather than used for power generation or industrial use, even as millions of Nigerians remain without reliable access to electricity.

According to data referenced in the Global Gas Flaring in 2024 report, NNPC-operated fields contributed over 60 per cent of the country’s total gas flaring, and 75 per cent of the increase observed last year.

Nigeria’s flaring intensity (12.0 c m per barrel) was more than twice the global average, underlining a severe inefficiency in energy resource utilisation.

A similar scenario is unfolding in Mexico, where flaring rose 4 per cent in 2024 even as oil production declined by 5 per cent.

Cantarell, Quesqui and Costero fields saw the steepest flare increases, driven by process upsets and inadequate reinjection infrastructure.

Pemex has promised upgrades to gas infrastructure in key fields, but progress remains sluggish.

Algeria, for its part, showed a nominal 4 per cent reduction in flaring volume.

However, because oil production also declined by 5 per cent, the flaring intensity still rose 2 per cent.

The Tin Fouye Tabankort field offers a more promising outlook. A deal allowed Sonatrach to route associated gas through adjacent infrastructure for processing and export.

It’s a replicable model, but only if supported by regulatory agility and private-sector collaboration.

The US, by contrast, has a more mixed but generally improving record. Nationwide, flaring intensity has fallen almost 50 per cent since 2012.

In the Permian Basin, flaring dropped 5 per cent in 2024 despite a 7 per cent rise in oil output, thanks largely to the launch of a new pipeline easing gas takeaway constraints.

However, the Bakken Basin tells a different story. Infrastructure bottlenecks there led to a 27 per cent surge in flaring, revealing how regional disparities continue to plague even high-tech oil provinces.

These disparities are not just technical but structural. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state-level regulators like the Texas Railroad Commission have taken steps to rein in flaring, but exemptions remain common.

With some operators reluctant to delay production for lack of takeaway infrastructure, flaring becomes a cost of doing business rather than an emergency measure.

GULF PRODUCERS: SHIFTING FROM FLARES TO FIELDS

In stark contrast, oil-producing states in the Arabian Gulf have largely eliminated routine flaring over the past two decades.

Saudi Aramco’s pioneering Master Gas System—developed in the 1970s—serves as a global model, capturing and processing virtually all associated gas for use in power generation, industry, and petrochemicals.

The Kingdom’s routine flaring rate is estimated at less than 1 per cent of raw gas production.

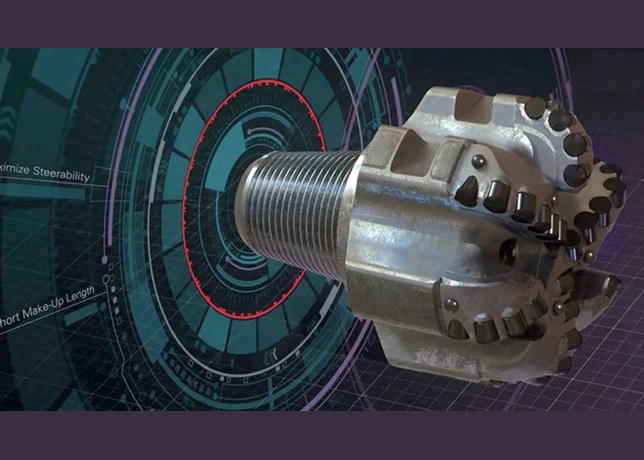

Aramco continues to modernise its systems with real-time leak detection, predictive maintenance using AI, and advanced flare minimisation technologies.

In 2023 alone, the company recovered an estimated 8.9 billion standard cu ft of gas that would otherwise have been flared, converting it into marketable fuel and reducing its greenhouse footprint substantially.

Other Gulf countries are following suit. The UAE and Qatar have made considerable strides toward eliminating flaring as part of their climate commitments under COP28 and their endorsements of the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 (ZRF) initiative.

QatarEnergy, for instance, integrates gas recovery and reinjection processes into nearly all its upstream operations.

And the UAE’s ADNOC has invested in carbon capture and reinjection systems and pledged to reach near-zero flaring across its onshore and offshore fields by 2030.

Kuwait and Oman have also launched similar programmes, though with varying levels of transparency.

Meanwhile, Bahrain, despite being a relatively smaller producer, uses nearly all its associated gas for domestic use, mainly in power and desalination. Its small size may have enabled quicker adoption of flare reduction technologies.

A key differentiator in the Gulf has been infrastructure foresight. Gas networks in Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar were deliberately designed to handle associated gas volumes from multiple fields, with interconnected pipelines and processing hubs.

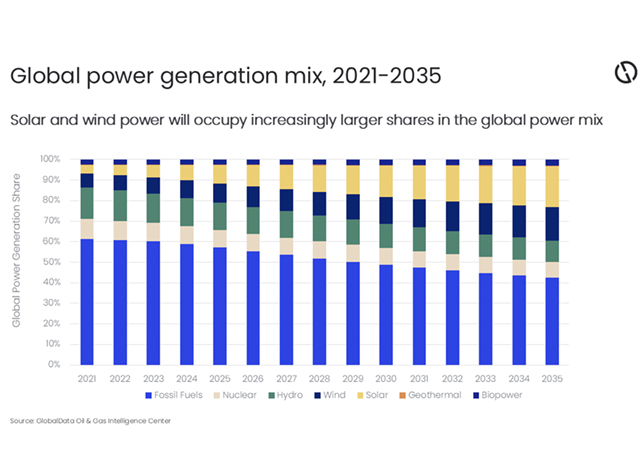

This eliminates the need to flare during routine operations and allows surplus gas to be stored, exported as LNG, or used domestically.

Moreover, these countries benefit from unified national oil companies with significant investment capacity and political will.

Their ability to act swiftly on flaring reduction goals contrasts sharply with countries like Nigeria and Mexico, where fragmented operations, outdated regulations, and financial constraints slow progress.

TECHNOLOGY AND REGULATION: TOOLS TO STOP THE BURN

The tools to eliminate flaring are not hypothetical; they are widely known, commercially available, and technically viable.

Flare gas recovery systems (FGRS), high-integrity protection systems (HIPS), and gas reinjection modules have become more cost-effective in recent years.

Even remote flare sites can now be connected using mobile gas processing units, small-scale LNG units, or compressed natural gas (CNG) trucks.

The World Bank’s Global Flaring and Methane Reduction (GFMR) Partnership stresses the role of policy.

Countries with clear, enforceable flaring bans (such as Kazakhstan and Egypt) have reduced flaring by up to 70 per cent since 2012.

These policies often include fiscal penalties for wasted gas, incentives for flare recovery, and tight monitoring protocols enforced through satellite tracking.

In the EU, the Methane Regulation adopted in 2024 requires importers to demonstrate low methane intensity and flare destruction rates of 99 per cent or higher.

By 2027, producers will need to show equivalency with European measurement, monitoring and verification (MMRV) standards, or risk losing access to European markets. This regulation could become a game-changer for oil-exporting nations.

However, persistent challenges remain. Countries like Libya, Venezuela and Syria still suffer from high flaring rates due to fragility and conflict.

Even in well-governed nations, smaller operators often lack the technical capacity or financial means to invest in gas recovery projects.

In these contexts, multilateral finance and technical support—like that offered by the GFMR—is critical.

A SQUANDERED RESOURCE; AND A MORAL QUESTION

Gas flaring wastes a vital resource in a world where 770 million people still lack access to electricity.

The irony of burning what could power schools, hospitals, and industries is hard to ignore.

It also undermines climate commitments, as flaring not only emits CO2 but releases potent methane when flares malfunction or remain unlit.

The 2024 flare volume (151 billion cu m) is enough to meet the entire natural gas demand of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The economic loss, when priced at average EU import levels, could fund nearly all the infrastructure investment needed to eliminate flaring globally.

The path forward is not unknown. Some countries are already walking it.

By Abdulaziz Khattak