Image by junak/ iStock

Image by junak/ iStock

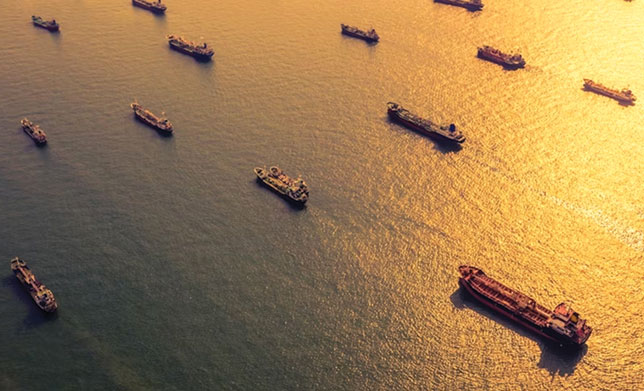

Countries at the UN shipping agency struck a deal on a global fuel emissions standard for the maritime sector that will impose an emissions fee on ships that breach it and reward vessels burning cleaner fuels.

The US pulled out of the climate talks at the International Maritime Organisation in London this week, urging other countries to do the same and threatening to impose "reciprocal measures" against any fees charged on US ships.

Despite that, a majority of countries approved the CO2-cutting measures to help meet the IMO's target to cut net emissions from international shipping by 20 per cent by 2030 and eliminate them by 2050.

Under the scheme, from 2028 ships will be charged a penalty of $380 per metric ton on every extra ton of CO2 equivalent they emit above a fixed emissions threshold, plus a penalty of $100 a ton on emissions above a stricter emissions limit.

Countries still need to give final approval at an IMO meeting in October.

The talks exposed rifts between governments over how fast to push the maritime sector to cut its environmental impact.

A proposal for a stronger carbon levy on all shipping emissions, backed by climate-vulnerable Pacific countries - which abstained in Friday's vote - plus the European Union and Britain, was dropped after opposition from several countries, including China, Brazil and Saudi Arabia, delegates told Reuters.

The deal is expected to generate up to $40 billion in fees from 2030, some of which will go towards making expensive zero-emission fuels more affordable.

In 2030, the main emissions limit will require ships to cut the emissions intensity of their fuel by 8 per cent compared with a 2008 baseline, while the stricter standard will demand a 21 per cent reduction.

By 2035, the main standard will cut fuel emissions by 30 per cent, versus 43 per cent for the stricter standard.

Ships that reduce emissions to below the stricter limit will be rewarded with credits that they can sell to non-compliant vessels.

MIXED REACTIONS

The IMO's deal triggered mixed reactions from member states, industry lobbies and campaign groups.

The European Commission called the deal "a meaningful step" towards achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change, while noting it does not yet ensure the sector’s full contribution to them.

Britain's transport minister Heidi Alexander said the deal would incentivise emission reductions and drive forward the development of clean fuels.

Ralph Regenvanu, climate minister of Vanuatu, one of the low-lying nations most exposed to climate change, said countries had "failed to support a set of measures that would have gotten the shipping industry onto a 1.5°C (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) pathway", referring to the level of global warming scientists say would avert the most damaging consequences.

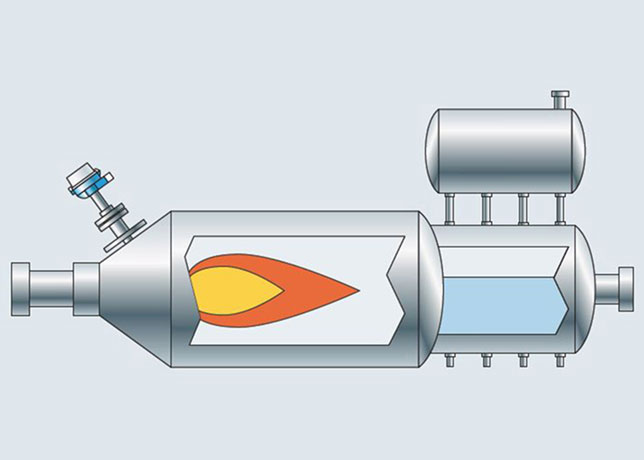

International shipping lacks available volumes of zero-emission fuels, such as green ammonia and methanol, but initially ships will be able burn LNG and biofuels to comply with the new rules, analysts say.

Welcoming Friday's deal and predicting a scaling up of production of new fuels, industry group the International Chamber of Shipping said "governments have understood the need to catalyse and support investment in zero emission fuels".

But campaign group Opportunity Green said there was a risk the IMO’s agreement would lock in the use of crop-based first generation biofuels and LNG, which is not carbon-free.

"The sector’s only credible path to net zero that doesn’t compromise biodiversity is green hydrogen e-fuels," Aoife O’Leary, head of Opportunity Green, said. -Reuters