KPC is creating a competitive environment for global bidders

KPC is creating a competitive environment for global bidders

Ever since KPC announced its intention to open up the upstream and invite international oil majors to develop its northern fields, it continued to face one challenge after the other.

The decision was met with extreme trepidation by the majority who feared that Kuwait would lose control over its natural wealth, especially since Kuwait had nationalised all operations in the 70s.

The first challenge KPC faced was to have a consensus on the need to re-invite the international oil companies to the upstream.

The idea to invite oil majors was conceived around 1995, when KPC had established a new production target to reach three million bpd by 2005, the issue was brought up by upstream specialists that Kuwait would not be able to achieve this target without active assistance from the international oil companies.

The increase in production required KPC to diversify the production beyond the large and easy reservoirs like Burgan, and go to more complex reservoirs with a deep-water cut.

The reservoirs by their nature would be higher cost so there was a concern about managing the future increase in production costs. It was felt that the expertise to manage the complexities of such reservoirs was not available within the local industry. So there was a strong conviction that the technical assistance of the international oil companies was needed.

Moreover, Kuwait was amongst the only three hydrocarbon rich countries in the world not using the capabilities of the international oil companies.

KPC had to address two important questions. First whether the Technical Service Agreements, which KPC had signed with three of the oil companies would suffice and secondly, whether the required expertise from the major service companies can be obtained.

However, the nature of the service agreements was that KPC got consulting and technical advice, while the companies did not shoulder the risk and or handle the decision-making.

As KPC shifted its focus to the more complex, and more risky reservoirs it became convinced that the nature of the relationship with the contract companies needed to change. It was believed that to get the best capabilities of these companies, and to attain their best resources, KPC needed to establish a relationship where they invested their money and were allowed to make the complex technical decisions.

The KPC management felt that it was wise to bring in the oil companies to invest and operate the fields and through them use the best capabilities of the service companies.

The second challenge was to have clear objectives as to what precisely KPC wanted to achieve and to define the objectives and put them to the oil companies so that KPC could evaluate any proposal from a common platform.

Common Platform: To obtain a better analysis, KPC studied the history of the upstream contracts, from the older concession type agreements to the more recent production sharing ones and finally the service agreements in Venezuela.

Since KPC's problem was to increase production from existing producing fields, and as there was no exploration risk, it was felt that the Venezuelan approach, modified to Kuwait's specific needs, was the most appropriate. However, one important consideration was to ensure that the agreement had is in line with the constitution.

Additionally, a major consideration within the structure of the relationship was the fiscal terms.

KPC had a clear objective to be able to compare different proposals or development plans from a common basis.

KPC realised that asking the oil companies to each give their proposals on the fiscal approach, would have made it very difficult to compare those contracts on an equal basis especially if their development plans were different.

While creating the fiscal terms, one overriding principle KPC had set was to ensure final transparency. KPC recognised that at the end of the process there would come the bidding stage and there it needed to be able to demonstrate that the choice of the winner was clear and transparent. This required KPC management to make common as many parameters as possible and not have too many variables.

So it was decided that the contract and the fiscal terms needed to be a common element given to the potential bidders. By deliberately choosing this approach of developing unique contractual and fiscal terms, KPC effectively chose a longer route.

Another challenge was to create a fiscal structure and relationship where KPC aligned the interests of the two sides. It was important that the elements of the fiscal terms did not create any incentive for the oil company to act against the interest of the state. The fiscal terms were set to ensure incentives for service companies to increase production in the most cost efficient way as they are also rewarded for cost savings. Another key objective was to ensure a stable long-term commitment from the oil companies.

At the same time KPC recognised that the structure also had to meet the objectives of the oil companies. The project had to be of a material size, and should allow them to earn an acceptable and competitive return, relative to the risk.

The final challenge was the political process. In choosing the contractual structure, KPC worked to ensure it was in line with the Kuwaiti constitution, and therefore did not require a new law as KPC wanted to have a speedy process.

It is a fact that Kuwait's constitution does not actually forbid a PSA or a concession agreement. It specifies that such agreements need to be enacted by law, should be for a specified time period and must be done through a process where there is publicity and competition.

KPC first wanted to be firm on the legal interpretation that service contracts were totally in line with the appropriate clauses in the constitution, and therefore there was no need for a law or Parliament's approval.

Then the second step was to apply to the new contract the same Parliamentary process as for a concession and enact it into a law. The third was to create a new 'umbrella' law, which would allow the government and the oil sector to execute service type agreements within certain agreed principles and processes. The last two approaches gave more of a role to the Parliament and was a less confrontational approach.

However to enact the agreement into law some serious problems had to be overcome. Firstly, the very technical nature of the detailed contract did not lend itself to a political debate and voting. Secondly in the negotiation phase it was unlikely that the oil companies would put their best terms if the Kuwaiti side did not have the authority to accept and commit to them. There were concerns that Parliament may force further concessions at a later stage. Thirdly any modifications needed in the future would require a law.

It was decided to prepare a new umbrella law, which was submitted, to Parliament. However progress was made difficult by domestic and regional developments, particularly with the Iraq crisis and the ensuing war to liberate Iraq. Nonetheless, KPC used this time to finish the work on the fiscal terms and contract.

On the commercial side, the train started to move again with the approval of the final 3 consortia and the submission of the draft contract and fiscal terms to them.

Despite the challenges KPC is confident that an agreement will be reached on the political process for the contract approval as the government had emphasised that Project Kuwait is a priority.

It was very important for KPC to create a process where there was not only transparency and publicity but also competition. By qualifying 17 companies and by directing them to form different consortia, KPC is creating a competitive environment, an environment where the leading companies of the world, acting through consortia, will have to submit their best proposals in competition with each other. Other countries in the region have chosen a different route where they negotiate directly with individual companies.

Challenges Facing Refining Ind-ustry: The refining and chemicals activities are two very important areas of the oil industry in Kuwait. They generate 58 per cent of KPC's profits, 44 per cent of the revenue, employ 59 per cent of the manpower and utilise 55 per cent of the capital budget.

On a combined basis it is expected that KPC will spend approximately $9.4 billion on projects in these two segments over the next seven years of which, $4 billion is for the chemicals side and $5.4 billion on the refining side.

Due to the small domestic demand, Kuwait's refining industry was built on the basis of export to the world, taking advantage of Kuwait's strategic location in the Arabian Gulf where it can serve the key regions of Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas.

Kuwait's key driver for entering the business was a means of diversifying from simply being a crude seller, and of deriving more value from the crude. So today KPC has three refineries in Kuwait with a total capacity of 912,000 bpd, one in Rotterdam with a capacity of 77,000 bpd and a 50 per cent ownership in a joint venture in Italy, in a refinery of 270,000 bpd, which means that about half of the crude production is refined.

The first challenge facing Kuwait's refining industry is the recent poor financial results of the international refining business. KPC worked with an international consultant who pointed out that most analyses demonstrate that the majority of refineries, over their life cycle, do not cover the cost of their capital due to two main reasons. The first is that in most markets, capacity generally exceeds demand. Secondly, once the capacity is installed, since the nature of the business is that the fixed costs are high but the variable operating costs are low, there is always the temptation to run additional barrels.

Another new feature, more relevant to Asia, is that the decline in the relative advantage that Asia enjoyed in refining margins and this is a phenomenon of the last 10 years.

To survive in such a low margin scenario, it is vital that KPC's refining industry focuses on achieving deep conversion so as to maximise high value product yield and on minimising the operating costs. Despite Kuwait's large conversion capacities, there is still a significant quantity of crude that is processed in hydro skimming mode. Detailed studies for the modernisation of the refineries are close to completion and KPC is in the final stages of deciding the process configuration for achieving a deep conversion-refining complex. The emphasis is on upgrading all the fuel oil at the Shuaiba refinery. On the cost side, KPC's refineries always rank highly on cash operating costs in the Solomon analysis.

Environment Friendly Industry: Another feature of the international refining industry is the fast changing and more stringent product specifications. Despite poor returns, the industry is faced with the persistent need to invest to accommodate the ever-changing shape of the demand barrel and, more importantly, the continued tightening of product specifications.

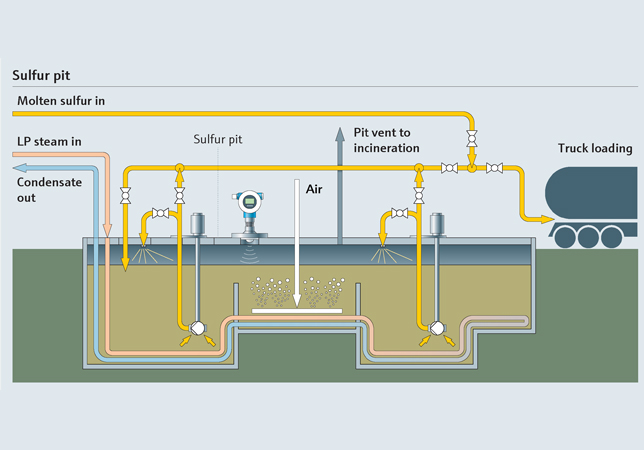

There is an increasing focus on the allowable level of sulfur in all fuels.

In the developed world, sulphur contents have to be brought down to 15-30 ppm by mid decade for gasoline and diesel and around 10 ppm towards the end of the decade. A number of regions are even moving to 'zero sulfur' fuels with sulfur contents of less than 10 parts per million.

Over time it is expected that the specifications in Asia will reach the same levels as those in OECD countries. As these specifications tighten, it is becoming more difficult to meet them with crude oil selection alone and therefore investment is required.

This is particularly the case in Kuwait as the crude is by nature of a high to medium sulphur quality so the investments that KPC needs to make are relatively more expensive. Since the refining industry in Kuwait is an export oriented refinery complex, it is essential that the quality expectations of the international markets are met. So a key focus for KPC in the next few years is to have a capability to produce ultra low sulphur transportation fuels.

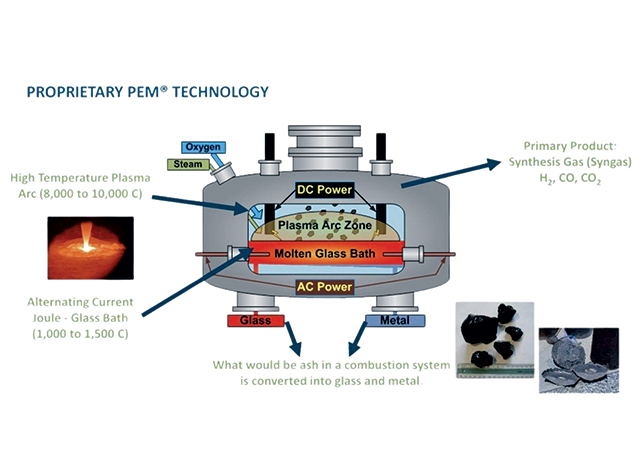

Another broad challenge being faced by international industry is the changes in vehicle technology. The transportation segment is probably the most important market segment for refineries. One has to bear in mind that future refineries will need to meet society's transportation needs, regardless of how vehicles are powered. So KPC has to prepare for vehicle technologies with new power requirements.

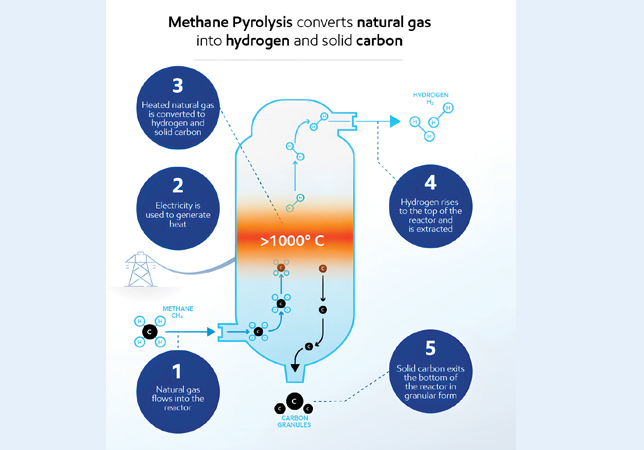

In the longer term, the emergence of low-cost, reliable fuel cells and a hydrogen economy could, of course, have further significant implications for transportation oil demand. At the same time, octane and additives, for example are not important for cars that run on fuel cells.

An important area that would complicate KPC's ability to rapidly respond to these fast changes is the move to a heavier and sourer slate of incremental crude production, mainly from new reservoirs. This is a departure from the previous heavy dependence on a single reservoir, namely the Burgan, for most of the production.

In future, all incremental crude production from the current level will come from the new fields and the qualities of oil from these fields are heavier and sourer.

By 2015, the heavier crude portion, with an API of 24 and lower, could be as high as 800,000, with half of this being below 17 API. Disposal of these heavy sour crude oils in the international market may pose problems and a more economic route may be to process them domestically in its refineries. KPC is currently studying the options to do so.

Kuwait's oil industry also needs to meet the growing fuel requirements for power generation in Kuwait while aiming to run the refining sector as 'merchant refineries'.

The gas production is limited and is mainly the gas associated with the crude oil production.

The net gas available as fuel for power generation is quite inadequate, when compared to the expected annual growth of about four per cent in electric power demand.

To meet this shortfall, and to serve as a strategic back up to the gas import initiatives, KPC is planning to build a new refinery, to process heavy crude and this could take the total domestic refining capacity to a maximum of 1.5 million barrels per day.

The fourth refinery construction will most likely be in two stages. The first stage will be building a crude topping refinery to convert all residues after desulfurisation to low sulfur fuel oil for power generation. The second stage will take up adding deep conversion facilities to coincide with the gas import materialisation. The apparent contradiction of producing fuel oil for power generation and also achieving deep conversion for domestic refining will be resolved with the import of gas and by building the refinery in two stages.

In the long term, all incremental fuel requirements for power generation are expected to be met from the gas imports commencing hopefully from 2006.

Challenges Facing Petrochemical Industry: KPC is seeking to diversify the energy portfolio to generate a greater percentage of growth and profits from the chemical business. The idea to build an Olefins plant was first conceived in the 70s. However, the project did not come to fruition until 1997. During this time KPC developed a fertiliser business, building urea and ammonia plants.

But the real push into petrochemicals, as opposed to fertilisers, was the joint venture with Union Carbide in 1997. This venture, which on its start up was considered to be the lowest cost producer of ethylene in the world, was also unique for KPC in another way. It was the first joint venture with a major international chemical company, and with the participation of the Kuwaiti private sector. This has proved to be a very successful business model and KPC intends to repeat it in their two expansion plans -- a new aromatics plant and a second Olefins complex.

Rich in Oil, Poor in Gas

The main challenge facing the petrochemical industry is the limited availability of gas, as feedstock, since all Kuwait's gas is associated gas. In fact, although Kuwait is a hydrocarbon rich country, it is also in fact a gas poor one. Since the gas is associated, its availability is tied to the Opec crude quota. The LPG plant, built in the 70s, was based on the previous crude production of three million bpd. Today it has one train idle as the crude oil production is close to two million bpd. At the same time, with the limited gas KPC has, the power generation sector has a competing and minimum need for it. This forms the background to the recent initiatives to import gas from Qatar and Iran.

The second challenge is that KPC has not yet developed a clear and consistent policy for the pricing of the gas, neither as feedstock nor as power. There are currently different levels of pricing and the parameters were set a long time ago. At the same time, it can be confusing to the small investors who are looking for a clear policy. Some parties are also requesting a level of subsidies to encourage the development of new industries, as is the practice in some of the neighboring countries. It is also complicated by the structural element whereby KPC buys the gas from the government but then re-supplies and re-sells it to the power, chemical, refining and other industries.

KPC is currently evaluating with the Ministry of Energy the key parameters for setting the gas price, taking into consideration the policies in the neighbouring countries, the request of the local industries but also the intrinsic gas value and opportunity costs.

The third challenge is the relatively small size of the domestic market for the end products, compared to bigger neighbours. This means that KPC has to compete in the international markets but without the low cost gas reserves of the major competitors in the region with their preferential pricing policies.

At the same time, the small size of the domestic market acts as a deterrent to investments. Investors are very open to make the investments and feel comfortable in supplying the local Kuwaiti market, which they know very well, but feel less confident in competing in the international markets without the same advantages.

Common Challenges

The common challenge facing both the refining and petrochemical sectors is the emphasis on creating new job opportunities. The oil sector currently employs 14,000 people directly and 17,000 via contractors. However, the next few years will see the addition of 18,000 new young nationals coming to the job market every year.

KPC is also working with the private sector to increase the percentage of nationals to at least 25 per cent is within the next three years.

.jpg)