Refinery mega-projects are necessary to process Kuwait’s increasing output

Refinery mega-projects are necessary to process Kuwait’s increasing output

MOTIVATED more by concerns about domestic power supply and guaranteed demand for its crude, Kuwait plans to boost its domestic refinery capacity by more than half to 1.4 million barrels per day (mbpd) within the next 10 years. Downstream officials say the cabinet could approve two refinery projects worth $30 billion, allowing contracts to be awarded about one year later.

The highest-profile project – a $14 billion new refinery at Al Zour – was approved seven years ago and has been delayed twice, most recently when contracts were withdrawn in 2009 after objections in parliament to the tendering process. Kuwait’s factious politics have continued to hold up the refinery, which will process up to 615,000 bpd of crude. Hopes that approvals could come in time for a 2016 start-up were thwarted when the cabinet resigned in March last; the finance and oil ministers sit on the Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC), which has final say on such projects.

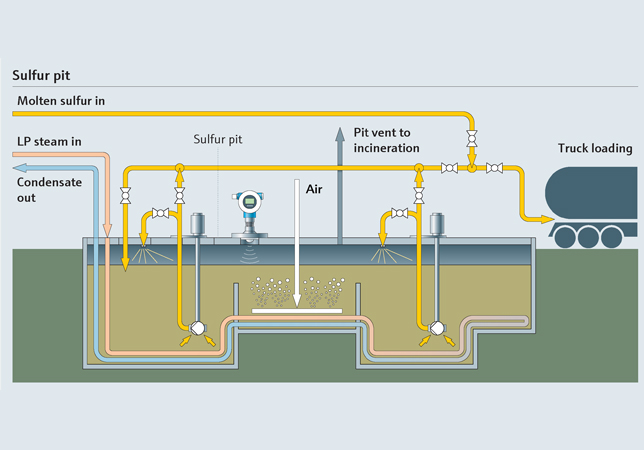

The other big development, the $16 billion-plus Clean Fuels Project, will increase capacity at the Mina Abdullah and Mina Al Ahmadi refineries, reduce the sulphur content of products, and concentrate on higher-value products such as naphtha and diesel.

In June, just as the newly reformed SPC approved the two refining projects, Kuwaiti parliamentarians announced an investigation into an upstream service agreement with Royal Dutch Shell to develop northern gas reserves.

The country’s national oil companies had been hit by a series of strikes last year. Oil industry officials are now treading carefully to avoid provoking further delays. Farouk Al Zanki, chief executive of the parent Kuwait Petroleum Corp, tried to counter any remaining suspicions, saying the downstream contracts would be subject to the same tendering process as all other projects. Officials acknowledge that the new refinery alone may not be profitable, but argue that it is essential to meet Kuwait’s rapidly growing power demand at a more reasonable cost. Last year, 14 per cent of Kuwait’s nonindustrial electricity demand was met by burning crude in power stations. “When you process the crude, we get fuel and products, but when we burn the crude we lose everything,” says Khaled Al Mushaileh, corporate planning manager at Kuwait National Petroleum Co (KNPC), the state downstream company. “So if you see the overall economics of Kuwait, this is the best alternative.”

The Ministry of Electricity and Water sees nonindustrial power demand growing by about 6 per cent per year through 2020, with overall demand – including the industrial and oil sectors – growing to 22,700 megawatts, from 10,890 MW now. At the same time, the country’s options have narrowed – plans for nuclear power generation were abandoned after Japan’s Fukushima disaster.

Kuwait has historically been short on gas, forcing it to import LNG through a temporary facility since 2009. While a team from KNPC and the upstream Kuwait Oil Co (KOC) recommended construction of a permanent LNG import facility, it is examining prospective locations before conducting a formal feasibility study. If KOC beats expectations and develops enough gas to meet electricity demand, Al Zour could be upgraded to produce more kerosene and diesel, Al Mushaileh says.

KNPC and KPC also argue that the refinery megaprojects are necessary to process the country’s increasing production of heavy crude, preserving the Kuwait Export blend for the overseas market. KOC expects to produce only about 60,000 bpd of heavy oil in 2016.