Schlumberger ... drilling for shale in Saudi Arabia

Schlumberger ... drilling for shale in Saudi Arabia

THE state-owned Saudi Aramco has asked US oilfield services firms Halliburton and Schlumberger to begin carrying out feasibility studies for the production of shale gas as early as possible, hoping the gas will be on stream seven years ahead of a previous schedule. Seismic surveys are currently being carried out in the northern desert area close to borders of Iraq and Jordan.

The work will be accelerated in 2013, when long-term development contracts will be tendered. Field services companies will be carrying out all underground activities which will include fracturing (fracking) the rock as well as drilling the wells.

It is expected that the main contracts will attract all of the US field services companies as they have the experience with shale gas. Halliburton, Schlumberger and Baker Hughes are all looking to secure any deal which will become available.

Saudi Aramco previously said it intended to develop its gas shale reserves by 2020 and had started a feasibility study to do this. However, with delays to some conventional gas sources, such as the Wasit Gas Development, it was forced to begin developing non-conventional sources early.

According to Baker Hughes, Saudi Arabia has the world’s fifth largest shale gas deposits of about 645 tcf. According to Saudi Aramco’s last annual report, the kingdom’s conventional gas reserves stand at 282.6 tcf. Although the figures offer a compelling case for major production, however, unlike conventional gas, shale gas is expensive to extract due to a number of factors.

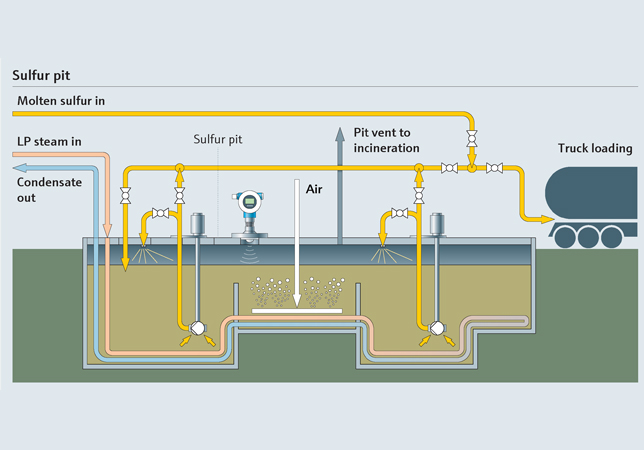

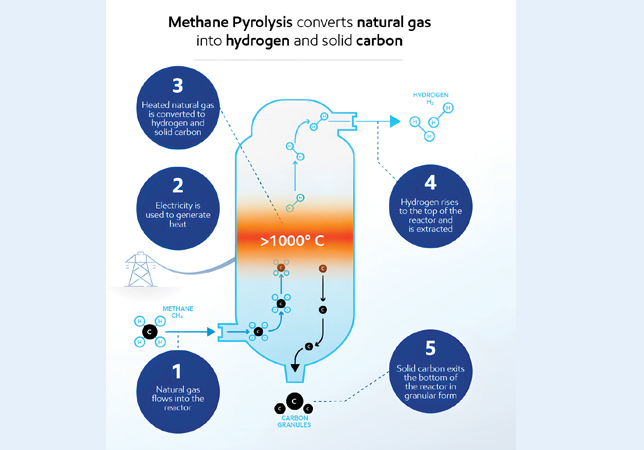

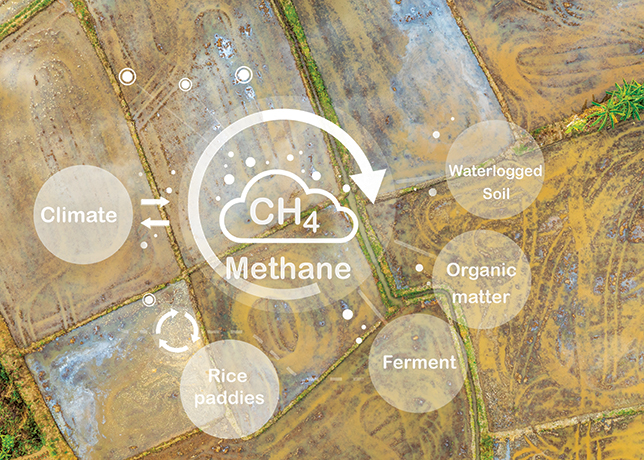

Shale gas is the same as conventional natural gas in composition except it is trapped between impermeable rock formations, usually deep underground. To free the resource, it is necessary to create permeability in the surrounding rocks to release the gas.

Creating permeability in rock to release gas thousands of metres under the surface is complex and expensive. This is achieved by a process known as fracking’, which involves drilling long horizontal sections and creating artificial permeability by fracturing as many as 400 wells.

Shale gas extraction requires a lot of water and a water source in northern Saudi Arabia which cannot be used for drinking or agricultural purposes will be a challenge to secure. Says a technical adviser to the hydrocarbons industry based in Saudi Arabia: “Shale gas is more promising than the recent gas exploration at the Empty Quarter, but make no mistake about it, this will be very expensive”. Due to the remoteness of the deposits costs would be as high $9/mmBtus (million British thermal units).

Once production of shale gas begins, the wells deplete very quickly and have to be replaced every two years. This adds expense to the overall cost of producing the gas.

The Saudi government now offers one of the largest subsidies for domestic uses of gas in the world and sells it at $0.75/mmBtus for industrial purposes. Selling shale gas at this figure would not be sustainable as a long-term domestic energy strategy.

However, Saudi Aramco’s aim is different. It wants the shale gas to replace crude oil being burned by the kingdom’s power plants. Crude oil is a very expensive fuel for the domestic power market. In the period between June and August 2012, for example, Saudi Arabia burned 766,000 bpd of crude oil to generate electricity – the highest level of use ever.

The government hopes consumption of crude oil by the Saudi market as a whole this year is expected to average more than 1.45 mbpd, and the use is rising by 8 per cent per annum.