FLNG is poised for take off in Malaysia

FLNG is poised for take off in Malaysia

MALAYSIA could become the world’s largest supplier of flexible liquified natural gas (LNG) by the end of the decade, according to consultants Wood Mackenzie, which cited new capacity additions both at Malaysia and worldwide that will bolster its supply portfolio.

Analysis from Wood Mackenzie suggests that state-owned Petroliam Nasional (Petronas)’ flexible LNG volumes could grow significantly in the coming years, reaching up to 26 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) in 2022 from the 2.5 mtpa registered in 2013.

Such growth could challenge Qatar’s position as one of the largest flexible suppliers currently in the market, according to Wood Mackenzie.

The consultant estimates that Qatar had some 20 mtpa of flexible LNG supplies in 2013, although it concedes that who will have the biggest flexible volumes in 2022 will depend on contracting strategies in the interim.

Overall, Petronas’ LNG supply is expected to increase over 55 per cent to reach 42 mtpa by 2022, up from 27 mtpa in 2013.

The company will add new capacity in eastern Malaysia with a planned expansion of Bintulu and a new floating LNG liquefaction plant in the next two years. It also holds stakes in projects in Pacific North West LNG, Canada, and Gladstone LNG, Australia.

While some of this new supply is already committed to long-term offtakers, Petronas will still need to place more volumes with buyers.

Some of its existing term contracts are also due to expire in the next 10 years and may not be renewed, contributing more incremental supplies to its portfolio.

LONG POSITION A BOON?

A long LNG portfolio would also prove beneficial for Petronas in a market where supply is predicted by many analysts to be tighter in the next few years, the Wood Mackenzie release adds.

“Flexible supply from its existing portfolio could be used to support marketing of Petronas’ PNW LNG project in Canada... this removes the pressure on delivery and provides customers with a diversity of supply sources,” Wood Mackenzie Asia gas research analyst Chong Zhi Xin says.

While this could provide the seller benefits through supply diversification, Wood Mackenzie concedes that Petronas could face challenges with its flexible LNG portfolio should the market become oversupplied.

Zhi Xin adds: “Petronas has the ability to find a market for its LNG domestically, an option not available to its competitors.” Data from Platts unit Bentek shows that Petronas rarely imports cargoes from its own facility in Bintulu.

The 3.8 mtpa Melaka terminal has received just one Malaysian cargo since its start-up in 2012, which arrived July 2014, suggesting that Petronas might already be exercising its option to supply its LNG into the domestic market.

The seller is widely heard to be holding surplus cargoes following the decline in demand from its term buyers in northeast Asia. Export data also reveals that Petronas has sold to Thailand, India and Kuwait in recent months – non-traditional buyers of Malaysian cargoes – as the seller looks to place incremental volumes after April annual delivery package re-negotiations.

Further out, the consultancy estimates that about 4 mtpa of LNG is necessary to balance the Malaysian domestic market by 2022, providing Petronas with some outlet for cargoes.

The release adds that Petronas could also swap out existing piped gas supplies in favour of LNG, putting imports as high as 8 mtpa.

However, Petronas currently has three LNG import agreements totaling more than 4 mtpa with France’s GDF Suez, Qatargas and Norway’s Statoil.

The seller will also offtake 3.5 mtpa from the GLNG project from 2015 onwards for 20 years.

Bentek data shows that Malaysia imported a total of 1.4 mtpa through its 3.8 mtpa Melaka LNG terminal in 2013. However, imports into the terminal are up significantly in the first seven months of 2014 versus the same period in 2013, hinting at a possible increase in demand.

UNLOCKS STRANDED GAS RESERVES

Meanwhile, as more small stranded gas fields are discovered in Malaysia, Petronas has moved to monetise these fields by building the world’s first commercial floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) facility.

“We are at the forefront of this new frontier and it is a bold step forward. It is a game-changer not only for Petronas and Malaysia but the entire oil and gas industry,” the national oil company’s executive vice-president of exploration and production (E&P), Datuk Wee Yiaw Hin, says in a report.

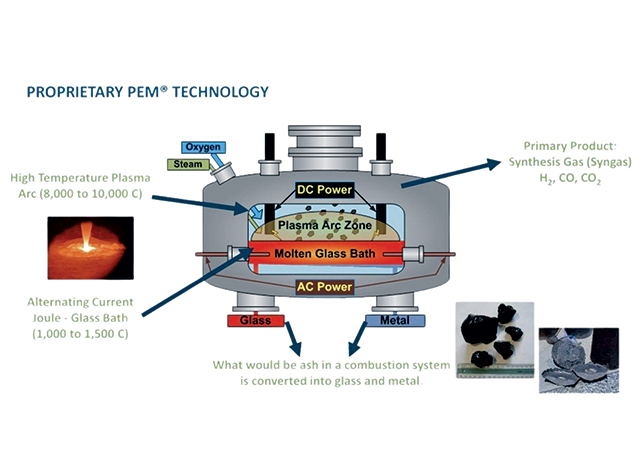

FLNG is a classic example of how technological advances enable the monetising of new resources, he says.

“The days of easy oil are over for Malaysia. We need to source more innovative monetising solutions for our fields and FLNG is one of the ways to do so,” he adds.

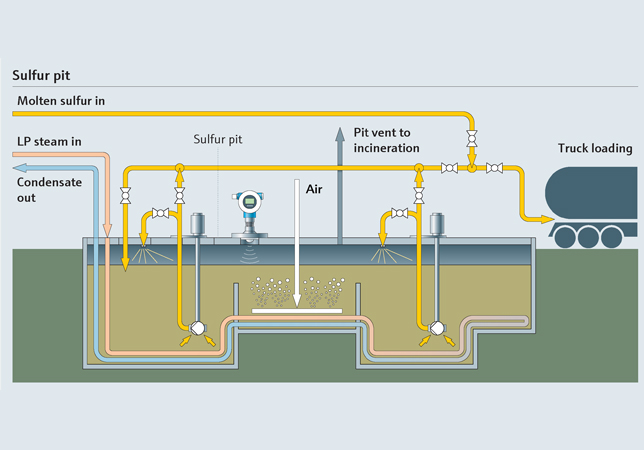

Instead of the conventional practice of transferring gas via pipelines to onshore LNG plants, an FLNG is able to go straight to the gas fields. The new facility will have an LNG plant on a vessel with full capacity to process, produce and offload LNG in-situ, near the source of the hydrocarbons or the gas fields.

Petronas’ first FLNG – known as PFLNG1 and worth $1.9 billion – is under construction in South Korea while its second – PFLNG2 ($2.6 billion) – is being engineered in Japan.

PFLNG1, which is aimed at developing gas fields in shallow waters, will be located in the Kanowit field in Sarawak and is capable of extracting 1.2 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of LNG. Petronas is building the facility, which is expected to be completed by end-2015, with its strategic partners Technip and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering.

PFLNG2 will develop gas fields in deep waters and be placed in Rotan, off Labuan. It has a capacity of 1.5 mtpa and is slated to be completed by early 2018. Petronas is partnering JGC Corp and Samsung Heavy Industries Co Ltd on this facility.

“In the context of dwindling production and maturing fields in Malaysia, we have little choice but to source new ways to develop and monetise harder to reach resources and to do so in such ways that still make economic sense,” says Wee, adding that it is neither cheap nor straightforward.

The floating facilities will enable the development of small and stranded gas fields without the need for pipelines, heavy infrastructure and other capital expenditure.

“FLNG is an effective solution to develop and produce resources from fields we wouldn’t have proceeded to as conventional methods have been found to be economically unfeasible,” Wee explains.

He says although developing gas fields using FLNG is slightly more expensive than onshore plants, it is the only means of unlocking stranded gas reserves economically.

“If the gas fields are close to shore, then we will tie them to onshore plants as that would be more economical. But for fields that are located far from shore, FLNG will enable us to monetise them efficiently.”

Wee also points out that Petronas’ aggressive exploration activities over the past three years have opened up a large number of stranded gas fields, especially in Sarawak. “To monetise these remote fields, we needed to invest in technology that would enable us to do so, thus increasing our LNG capacity.”

Currently, Malaysia is the second largest LNG exporter in the world, behind Qatar. It has eight LNG trains with a capacity to produce about 25.8 mpta. With the addition of Train 9 and the two new FLNG facilities, the country’s LNG production capacity will widen to 32.1 mpta by 2018.

With the new facilities, Wee says Petronas will see an increase in the contribution from its LNG business. In the first quarter of 2014, the business contributed about 35 per cent to Petronas’ revenue of RM84 billion.

FLNG may be set to revolutionise the oil and gas industry, but Petronas is not the only one in the game. Shell is also building a FLNG facility with a capacity of 3.6 mpta in Australia. It is expected to be completed by 2017.

Nevertheless, the two oil giants are looking at different niches. While Shell is looking at bigger FLNG facilities to handle rough seas and larger gas fields, Petronas is aiming for small fields.

“We are going for a smaller facility as it is nimbler and faster. Our aim is not to build the biggest in the world. In fact, having a smaller capacity FLNG allows greater flexibility to achieve our purpose,” says Wee.

Although Petronas’ two FLNG facilities will have the task of developing Malaysia’s stranded gas fields, they have full flexibility and can work on international fields.

“It will take about 15 to 20 years to develop all our small gas fields, but if the opportunity arises and we discover small gas fields overseas, we will look into building another FLNG,” says Wee.

He adds that other international parties are also interested in FLNG facilities but they are unable to get started on them. “Not everyone can build an FLNG. It requires scale, integration and advanced technology. You also need deep pockets to venture into it.”

Companies may also not have the full value chain to venture into such projects, says Wee. “Petronas is able to integrate its upstream business with the LNG technology and we have the tankers, the fields and the market, which makes it an economical project for us to take on.”

According to Wee, once the FLNG facilities are operational, theirs will become a tried and tested technology that can be replicated anywhere, not just in Malaysia. “This facility and technology is something Petronas will be able to offer other countries hoping to monetise their gas fields without incurring the capex for conventional infrastructure.”