Wheeler ... Guyana has good offshore prospects

Wheeler ... Guyana has good offshore prospects

Guyana's prominence in the international hydrocarbons market has risen considerably in the past year. ExxonMobil’s announcement in May 2015 that it had discovered an estimated 700 hundred million barrels of oil offshore Guyana, launched a tide of interest from oil majors, wildcatters and service companies, all of whom descended on Georgetown, says Eric Wheeler, Associate at The Risk Advisory Group.

ExxonMobil’s discovery in the offshore Stabroek block has been followed by a raft of new agreements signed by the Guyanese government and interested companies. Repsol, active in Guyana since 2012, has renewed its interest in the offshore Kanuku block and has applied for a new exploration license for an ultra-deepwater block.

In early 2016 UK-based Tullow Oil was granted a 60 per cent operating interest in Orinduik, an offshore block adjacent to Stabroek. Canadian-Guyanese joint venture CGX Energy holds three exploration licences and smaller oil and gas firms have signed new farm-in agreements with oil majors in offshore prospects, he says.

Interest from outside Guyana has so far been met with enthusiasm from within the country. Publicly and privately, Guyanese President, David Granger, and Minister of Natural Resources and the Environment, Raphael Trotman, are of the same mind in affirming the country’s commitment to the growth of its nascent hydrocarbons sector.

Both have pledged support for new legislation and better governance for an extractive sector that was previously limited to mining for gold, diamonds and bauxite in the Guyanese Amazon.

Similarly, officials in the extractive sector’s oversight body, the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission, are in the process of finalising new production-sharing and royalty arrangements while the country’s recently-passed 2016 budget includes allocations for new oil and gas equipment.

However, like other frontier markets, Guyana faces a set of challenges that could derail the country’s ability to convert its burgeoning hydrocarbons sector into meaningful development. One of the more immediate is a lack of physical infrastructure.

Before 2014 Guyana had no proven, commercially viable hydrocarbons reserves. It’s no surprise then that the country’s only commercial port, the Port of Georgetown, is ill-equipped to handle anything more substantial than a small cruise ship.

There is general agreement that a bigger and better port is needed. The question is where to develop it. Some insist that Georgetown is the most apt. Others say that Berbice, a comparatively undeveloped region in Eastern Guyana, is more suitable for development - given its lower levels of sedimentation, and the fact that the port could be purpose built for oil and gas tankers.

Onlookers are hopeful that the Guyanese will make a decision one way or the other soon, and proceed accordingly, Wheeler says.

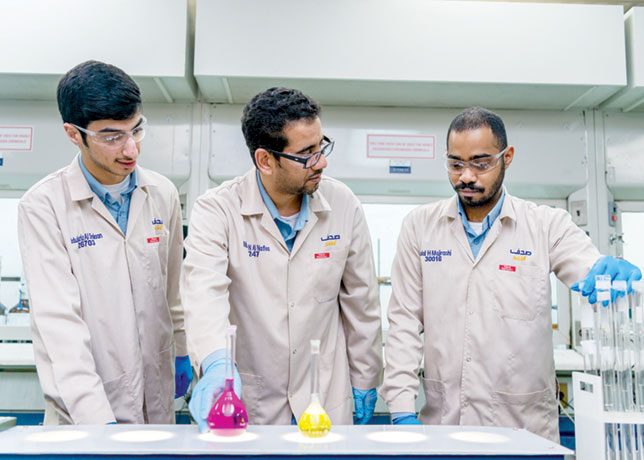

Compounding the lack of physical infrastructure is a chronic shortage of human capital. Guyana’s state-controlled education system is one of the weakest in the Caribbean, and lacks an established petroleum engineering curriculum.

While the country does graduate a meaningful number of engineers, local employment prospects are such that Guyana has long suffered from brain drain. Here too, the country’s leadership is trying to make amends, and has spoken publicly in support of an initiative to create opportunities for Guyanese engineers and technocrats.

But it takes time and money to build a skilled domestic workforce, and although officials in the country’s Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment anticipate that offshore production could begin as soon as 2018, they warn that laying the educational foundations for meaningful domestic employment in the oil and gas sector could take closer to a decade.

Infrastructure and human capital challenges are not the only threats looming on the horizon. The discovery of oil rekindled an ages-old border dispute with neighbouring Venezuela. Shortly after ExxonMobil made its discovery, the impoverished Venezuelan government revived a 100-year-old claim to significant portions of territory west of the Essequibo river in Western Guyana.