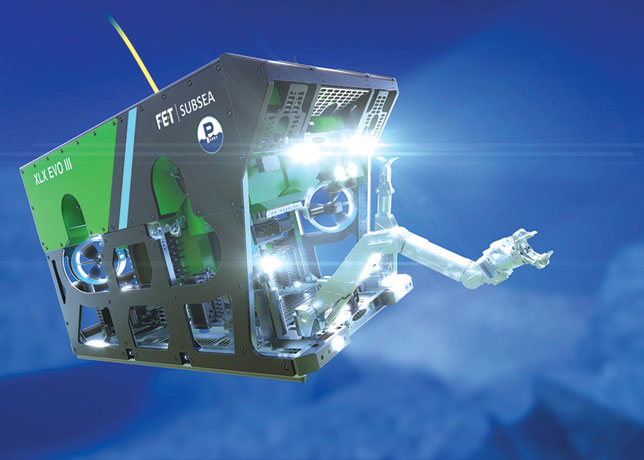

Saudi Aramco’s offshore Hasbah oilfield

Saudi Aramco’s offshore Hasbah oilfield

The 25 per cent boost in spending to $414 billion comes as Saudi Aramco prepares for its much-anticipated initial public offering (IPO), which Saudi officials still say will happen in the second half of 2018

State-owned oil giant Saudi Aramco plans to boost its 10–year spending plan by about 25 per cent to $414 billion as the firm expands its activities beyond oil and gas, an official presentation by a senior Aramco executive showed.

The boost in spending comes as Aramco prepares for its much-anticipated initial public offering (IPO), which Saudi officials still say will happen in the second half of 2018.

'Our numbers compared to the total previous business plan, it increased definitely ... [we expanded] into other sectors,' Aramco CEO Amin Nasser says.

Asked to explain the big jump in the spending plan, Nasser explained that previous figures – including an August estimate of $300 billion over the next decade – may have been only accounted for investment in the oil and gas sector and did not include Aramco’s other complementary businesses such as infrastructure. However, he did acknowledge there was an overall increase in the total spending plan.

Even so, the world’s largest publicly listed international oil companies like ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, Total and BP continue to demonstrate spending restraint, adhering to capital discipline that investors now demand. It’s unclear how investors eyeing the Aramco IPO will view the sharp jump in investments, particularly if they are directed outside the company’s core oil and gas operations, where profitability may be weaker.

The previous $300 billion spending plan floated by Aramco executives was designed to maintain the kingdom’s oil production capacity and develop large exploration and production projects in conventional and unconventional resources, with a significant focus on offshore schemes.

Nassir Al-Yami, Aramco’s procurement general manager who revealed the new spending plan at the conference, says it would ensure that the majority of outlays will happen within the kingdom and thus help satisfy a local service and content target of 70 per cent by 2021. Currently the rate is considerably lower as Aramco relies heavily on foreign contractors.

|

Nasser ... continuing to invest |

'Saudi Aramco is expected to spend more than 1 trillion Saudi riyals over the next decade ... we still want to see 70 per cent of those riyals being spent locally,' Nasser says.

IPO investors will also look closely to see how local service and content requirements affect Aramco’s profitability, particularly if this work can be performed more cheaply by outsiders.

The new figures suggest that Aramco plans to spend around $41.4 billion annually for the next 10 years, up from around $30 billion under the previous plan. However, spending does not happen in equal portions each year. For example, for the current fiscal year Aramco has allocated $93 billion for capital spending, according to Aramco’s senior vice president of technical services, Ahmad Al-Saadi.

'The bulk of the spending has happened this year but I think there will be a small increase in spending next year and then you will see a slower pace as there are less big-ticket projects,' says a Saudi-based industry source familiar with the matter.

As a general trend, capital spending by state-owned oil companies in the Gulf region has been more resilient to the oil price downturn as they take a longer-term view to maintain and expand their capacities.

So far, Aramco has no plans to increase its total capacity of 12.5 million barrels per day (mbpd) but is keen to expand its industrial projects, maintain its current capacity and boost its local gas supplies. According to the new plan, Aramco would spend $134 billion over the coming decade on drilling and well services, another $78 billion to maintain output capacity and $19 billion on its gas programme.

That would put upstream spending at around $231 billion, or more than half of the overall programme, and leave the rest for downstream and other industrial ventures.

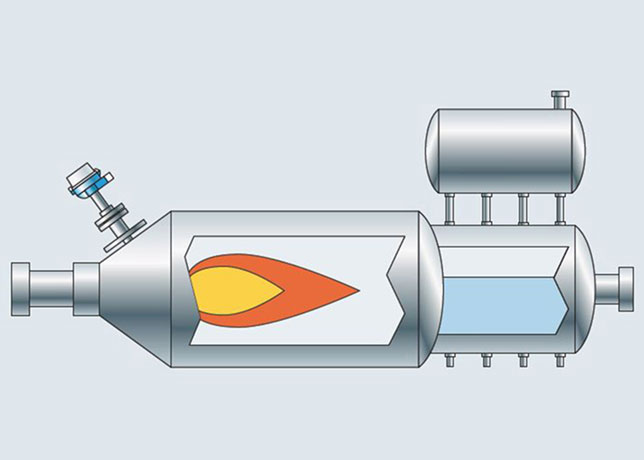

With a target to double gas production over the coming decade, Saudi Arabia’s hunt for gas to keep up with domestic demand is intensifying. The kingdom’s low-cost conventional gas resources are insufficient to meet this target, leading state oil champion Saudi Aramco to start delving into more challenging unconventional reservoirs in the northwest, South Ghawar and Rub al-Khali desert over the past few years.

|

Manifa ... repairs being done |

Former Saudi Oil Minister Ali Naimi estimated previously that the kingdom holds more than 600 trillion cubic feet of unconventional gas reserves, more than double its proven conventional reserves. Aramco CEO Amin Nasser said last year that the Jafurah Basin, located southeast of the giant Ghawar oil field, showed 'promising quantities and economically feasible' shale gas reserves, although it is unclear what work has been done to date. PIW understands that the basin’s Jurassic Tuwaiq Mountain formation requires drilling several wells over a very large area, adding to costs.

Oil service companies working with Aramco say studies have meanwhile been conducted in the Al-Hasa region near the kingdom’s border with Qatar, but high costs and a lack of water have made extraction uneconomic for the time being.

Aramco has not said much about its shale and tight gas resources. Albeit, it is close to completing the System A project in the northern region of Turaif, which will produce shale gas to feed the Waad al-Shamal industrial phosphate project.

'The results of this project are very promising and a learning experience for other projects,' an industry source says. Waad Al-Shamal should be receiving some 55 million cubic feet per day of gas by the end of this year, Aramco says. The state firm is also building gas processing facilities and drilling out the System B scheme, which should add 200 mmcfd in Turaif, and is planning to award the System C development. Aramco claims Saudi Arabia 'will be among the first countries outside North America to use shale gas for domestic power generation.'

Of the 23 billion cubic feet per day of gas Saudi Arabia hopes to produce a decade out, 2-3 bcfd is expected to come from shale gas. Ideally, Aramco would prefer to meet this overall target with its own resources, but to do so it will have to overcome the significant challenges – high costs, limited access to water, harsh desert environment and unique geology. A desire to minimise the time and effort required to overcome these obstacles could be why Saudi Aramco might be sniffing around the US shale gas patch. Aramco is said to have already spent billions of dollars on the equipment and technology required to bring on around 70 mmcfd from System A.

Aramco is partnered with Japan’s JGC, although it is unclear which specific technologies are being applied. There are established industry technologies, such as Schlumberger’s Hi-Way hydraulic fracturing completion system, that are designed to limit water needs. But the kingdom has special needs.

For instance, its very fine sand has a high salinity that complicates its use as a proppant to hold open shale reservoirs as they are broken up through fracking.

Unlike in the US, which gave birth to shale gas development, Saudi Arabia lacks the tens of thousands of vertical wells drilled in areas prone to shale that the industry could use to calibrate horizontal well trajectories and evaluate formations while limiting costs. The majority of areas where Aramco has identified shale gas resources are instead located far from its legacy oil fields.

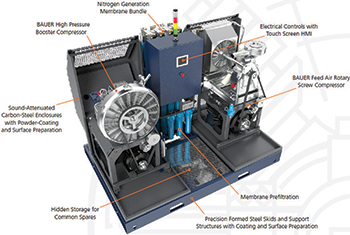

Meanwhile, Aramco has awarded a contract to conduct repairs affecting its 900,000 bpd offshore Manifa field to engineering firm Saipem, industry sources say.

Manifa’s water injection system was damaged by high-salinity water, causing a major rupture in one of the 55 km water injection pipelines and shutting in one-third of the field’s production capacity.

The scope of work includes the replacement of the pipeline, known as Flank 1, and overall, the repairs are expected to be completed within a tight schedule of 12 months, according to sources familiar with the matter.

The corrosion at Manifa’s water injection system was a surprise to many technical experts given that its installation was only completed in 2008. Sources close to Aramco say that the current pipelines were installed by McDermott, but Aramco did not request that the US contractor coat the pipeline internally for protection. McDermott says in a statement that it does not comment on specific tenders. Saipem was unable to comment.

Manifa can pump 900,000 bpd, but prior to the corrosion issue the field’s production averaged 800,000 bpd, according to a source familiar with Aramco’s operations.

Aramco argues that the problems at Manifa do not affect the company’s overall production capacity of 12 mbpd. Other Saudi fields can compensate for the production losses at Manifa up to 300,000 bpd, says an informed source.

The repairs to the water injection system are aimed at helping the field maintain its production recovery rates over the long term.

While the Manifa troubles are a major source of concern for Aramco, it should not affect Saudi Arabia’s ability to adequately supply world oil markets. The kingdom’s decision to cut beyond its Opec allocation in November and December opens a window of opportunity for state-owned Aramco to carry out repair work at the offshore oil field without having to push its other fields to compensate the difference in output loss, Saudi industry sources say.

Oil majors are increasingly engaged in the climate debate and making some investments in low-carbon technologies, although it’s clear they still don’t see an imminent threat to either oil or gas demand – a position many climate campaigners see as being essentially contradictory.

This industry position was in evidence at an Economist Energy Summit in London, where executives from both BP and Saudi Aramco sought to emphasise that while renewables would see ample growth in the years ahead, for now at least, they don’t see a risk to oil demand.

David Eyton, BP’s head of technology, told the conference that while some things 'have changed,' such as the global push to address climate change, at the same time others haven’t, such as expectations for growing world energy demand that can only be met by hydrocarbons.

Indeed, Eyton says BP expects oil demand to remain 'buoyant,' although he admitted it may be 'damped somewhat' by the growth of electric vehicles, for example.

Ahmad Al Khowaiter, chief technology officer at Saudi Aramco, also suggested that talk of 'peak demand' was 'exaggerated' and that the firm remains 'confident' about oil’s long-term role. While some suggest that oil demand could plateau around 2025 –Royal Dutch Shell says it’s possible in the late 2020s – Al Khowaiter says he sees oil demand continuing to rise to the late 2040s.

Aramco, which holds the world’s largest oil reserves estimated at around 260 billion barrels, would obviously benefit from such a scenario playing out.

However, Riyadh’s plan to sell up to 5 per cent of Aramco in an initial public offering (IPO) has prompted some observers to question whether Saudi Arabia is more concerned about climate-related peak oil demand and 'stranded assets' than it is letting on.

But Al Khowaiter says demand growth will be driven in a large part by the continued need for oil in transport. People, 'overplay' the potential for electric vehicles pushing out oil from light-duty vehicles, the Aramco executive added, suggesting that while the likes of Tesla may sell cars in rich OECD countries, this won’t be the case in developing economies.

Also, he says, demand will continue to come from heavy-duty transport. And although Al Khowaiter noted the potential for technological advancements in trucks, with Telsa’s recent announcement of a new electric 'Semi' tractor-trailer, he says he remained skeptical about the costs involved. Aircraft will also continue to fuel oil demand growth, as will petrochemicals, Al Khowaiter added – pointing to expected petrochemical demand growth of around 4 per cent per year.

The Saudis have expressed concerns that weak oil investment levels since the oil price collapse three years ago could lead to sharply higher prices.