The Dammam 7 well that changed the history of Saudi Arabia

The Dammam 7 well that changed the history of Saudi Arabia

When oil was discovered in Dammam 7 well, little did people know that the Dammam Field would become but one bead in a whole necklace of discoveries by Aramco. Of all the thousands of wells drilled in Saudi Arabia since, Lucky No 7 is the symbol of first success

The below narration is an edited version of an article written by Mary Norton and published in the May/June 1988 edition of Saudi Aramco World

Following the oil concession agreement between Saudi Arabia and Standard Oil Company of California (Socal) in May 1933, the search for oil began in the fall, on September 23, when American geologists Bert Miller and Krug Henry crossed to the Saudi mainland from Bahrain.

They landed at the sleepy coastal village of Jubail, about 105 km north of the Dammam Dome. They examined those rugged hills within a week of their arrival.

After surface mapping and aerial reconnaissance, and though exploration parties were working intensively in other locations, the Dammam Dome remained the best bet, and Miller recommended that the search for oil should begin there. The hope was that they would find oil at the same depths as on Bahrain - in the 600-m (2,000-ft) range known as the "Bahrain Zone".

[Socal chose California Arabian Standard Oil Company (Casco), a subsidiary, to do the work, and drilling began in 1935.]

The wildcatters – drillers, rigbuilders, and construction men who came over from Bahrain in the fall of 1934 – were men like the geologists in their light-hearted affection for challenge, their stamina, and their undaunted – and well-founded – belief in their own abilities.

Still, the Dammam Dome tested them. An early edition of the Aramco Handbook states that "not only the drilling rig and equipment, but every item of lumber, hardware, plumbing and steel needed to create and supply living quarters, pipe for water, transportation equipment and spare parts, food and personal requirements had to be brought over in a supply line reaching from the United States." In addition, water wells had to be drilled, roads built and power provided where none of these things existed.

With the help of Saudi recruits, for whom drilling – and indeed the very notion of scheduled shift work – was entirely new, Dammam No 1 was spudded in on April 30, 1935, using an old cable-tool rig. The obelisk-shaped derrick, the area's tallest structure, looked out over desolate terrain that was hardly softened by distant black Bedouin tents. After seven months of sputtering between hope and disappointment, the well produced a strong flow of gas and shows of oil just short of 700 m down (2,300 ft) – but an equipment breakdown forced the crew to kill the well and later plug it with cement.

The drillers rigged up Dammam No 2 the same day. No 2 was almost too good to be true. Spudding in on February 8, 1936, the crew had drilled to a depth of 663 m by May 11. This was the targeted Bahrain Zone, and from it came a flow of 335 barrels of oil a day when the well was tested in June. A week later, after acid treatment, it flowed at the equivalent of 3,840 barrels a day, just like that.

|

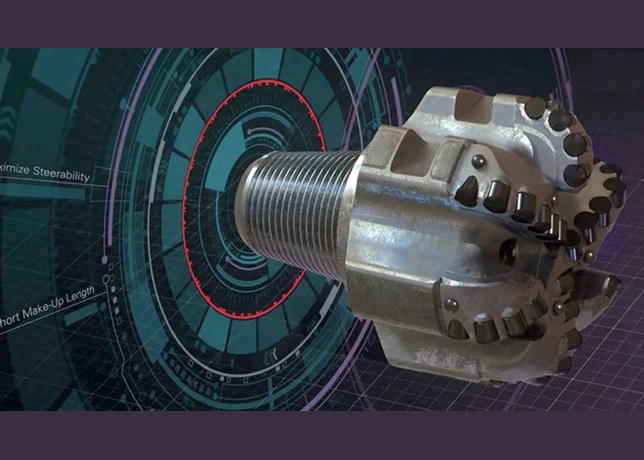

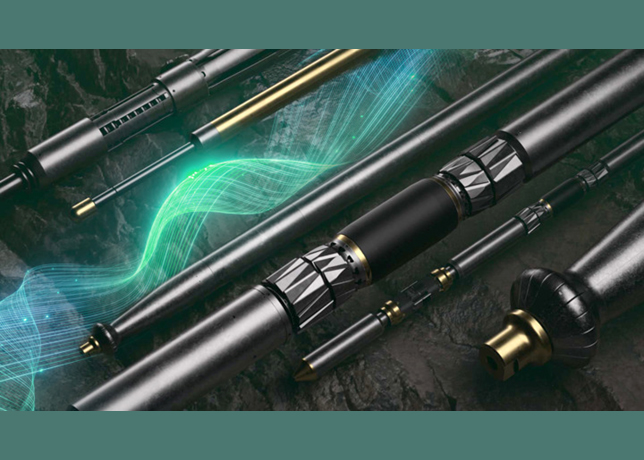

A drilling crew at Dammam 7 in 1938. Photo: L Hilyard/courtesy: Aramco |

The news was what the Casoc had wanted – and needed - to hear. Back from San Francisco came instructions to put down Dammam Nos 3, 4, 5 and 6. Contrary to the cautious industry practice of awaiting proof of field size and commercial viability before establishing a permanent camp, Casoc ordered a shipment of air-conditioned family cottages, as well as several bachelor housing units. And for good measure, word came in July to prepare Dammam No 7 as a deep-test well.

More work meant more men and more material, and soon there was more of all three than the camp could handle. By the end of 1936, the number of American employees in the field had risen from 26 to 62, and 1,076 Saudis had joined the strange new enterprise. About that time, however, things about the drilling rigs started to turn sour.

Dammam No 1, drilled to below 975 m, proved a loser. No 2 "went wet" and started producing eight or nine times more water than oil. Dammam No 3 had a flow of no more than 100 barrels of heavy oil a day, with 15 percent water. No 4 was dry as a bone. No 5 had no production either. A wildcat well at al-Alat, a prospect 20 miles northwest, was a bust all the way down to 1,380 m. Dammam No. 6, drilled in early 1937, showed only a little oil mixed with water.

On December 7, 1936, the wildcatters had spudded in the deep-test well, No 7. The other wells had been disappointing, but when it came to trouble, Dammam No 7 proved to be in a class by itself.

There were delays and stoppages. Drill pipe stuck. Rotary chains broke. Bits were lost down the hole and had to be fished out, and walls caved in. As the steam-driven rotary rig ground toward the Bahrain Zone, the results remained the same: No oil. No oil.

Ten long months later, on October 16, 1937, at 1,097 m, the drillers saw the first sign: two gallons of oil in a flow of mud cut with belches of gas. Then, on the last day of the year, control equipment failed and the well blew out. After drilling 1,382 m into their best prospect, the Casoc crews hadn't found enough oil to fill the crankcases of their own trucks.

The optimism of 18 months before began to look foolish, and a somber mood descended on Socal's management.

Chief geologist Max Steineke, who knew more about Saudi Arabia's geology than anyone, was called to San Francisco early in 1938. Since his arrival at Jubail in late 1934, the insatiably curious and energetic Steineke had ranged far and wide in the concession area.

Waiting to hear his opinion were men who had gone far out on a limb in the expectation that oil would by now be found. Some could already hear, in their minds' ears, the wrath of their stockholders, and were more than ready to pull out of the Saudi Arabian venture altogether.

But Steineke had never wavered in his belief that oil lay beneath Saudi Arabia's stratigraphy, and now he stood his ground. Still unable to prove his hypothesis, he fell back on his formidable knowledge, intuition and optimism.

He was dramatically vindicated. In the first week of March, 1938, while Steineke was still arguing his case in San Francisco, Dammam No 7 found what it was looking for at a depth of 1,440 m – less than 60 m farther down. It flowed 1,585 barrels a day on March 4; 3,690 barrels on March 7; 2,130 nine days later; 3,732 five days after that; 3,810 the next day; and so on until the head office cabled that they saw no reason to continue the test. Dammam No 2 and Dammam No 4 were also deepened to the Arab Zone and they too proved good producers. Dammam Field was declared a commercial producer.

Jubilation reverberated from Dammam Camp to Riyadh and San Francisco.

Saudi Arabia's King Abdulaziz Al Saud had given all possible cooperation to the venture, and not long after October 1938, when the presence of oil in commercial quantities was officially declared, plans began to unfold for his visit to Al-Hasa, as the Eastern Province was then known.

In the spring of 1939, the King and his retinue moved east from Riyadh in a caravan of 2,000 people in 500 cars, across the red sands of the Dahna and along desert tracks to a place near the oil camp, officially named Dhahran only 10 weeks before. In an atmosphere of conviviality, the visitors set up a city of 350 white tents within view of the camp for festivities which included inspections, banquets, receptions and boat rides in the Gulf.

The timing of the visit coincided with the completion of a 69-km pipeline from the Dammam oil field to the port of Ras Tanura, where the tanker D G Scofield lay waiting.

On the last day of celebrations, Wallace Stegner (writer of Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil) recounts, King Abdulaziz Al Saud unhesitatingly "reached out the enormous hand with which he had created and held together his kingdom in the first place, and turned the valve on the line through which the wealth, power and responsibilities of the industrial 20th century would flow into Saudi Arabia. It was May 1, 1939."

What people knew at the time was truly cause for celebration: Oil had been found and was being produced. What they did not know was that the Dammam Field would become but one bead in a whole necklace of discoveries by Aramco, including Ghawar, the world's largest onshore field, and Safaniya, the world's largest offshore field.

Spreading out to explore distant corners of the million-square-kilometre concession area, the pioneering geologists could not have imagined that one-fourth of all the world's oil lay beneath their feet.

Dammam No 7 stands on a hill named Jabal Dhahran - the surface expression of the Dammam Dome – near a cluster of peaks called Umm al-Rus. Today, Aramco's gleaming high-tech Exploration and Petroleum Engineering Center (Expec) lies just up the road, and the company's headquarters community of Dhahran just beyond. The town, green and comfortable, is far different from the drilling camp it once was, and the silicone-chip and stainless-steel technology of Expec is light-years beyond that of the 1930s; nonetheless, Aramco has never lost sight of its geological roots.

Of all the thousands of wells drilled in Saudi Arabia since, "Lucky No. 7", as it came to be called, is the mascot, the symbol of first success.

Photo 1: The Dammam 7 well, also called ‘Prosperity Well’ and ‘Lucky 7’, that changed the history of Saudi Arabia

Photo 2: A drilling crew poses on the steps of Dammam 7 in 1938. A drilling crew comprised an American driller, an assistant driller and 12 Saudis. Photo: L Hilyard/ courtesy: Aramco