Zanganeh ... Oman will become the marketing centre for Iran

Zanganeh ... Oman will become the marketing centre for Iran

Key for Oman’s oil and gas sector is the prospect of Iranian investment in the planned Duqm refinery and the deepwater port and industrial city

Muscat remains quietly optimistic that its latest plan to import Iranian natural gas will bear fruit, but talks with Tehran remain at an early stage and the route of a proposed 300-km pipeline is still undecided, Oman’s oil and gas minister says.

Unlike in the past, the sticking point for discussions is not the pricing formula for the gas, Mohammed Al Rumhy says.

"The issue of pricing Iranian gas, we have agreed we will leave this to the end of the project," Al Rumhy says. "Many factors will determine how we price it. The ultimate goal from this side of the water is to build this as an infrastructure project. I think it’s good for our energy security."

Al Rumhy acknowledges that negotiations between Tehran and Muscat over a similar project envisioned in a 2005 memorandum of understanding bogged down over pricing, leading the project to be shelved.

"Ten years ago, we made the discussion too complicated by starting with pricing," he says. "This time we want to try a different approach by putting infrastructure first and price last."

Under the current round of negotiations, the first step, which is under discussion, was to agree on a pipeline route. Next would come pipeline design, Al Rumhy says.

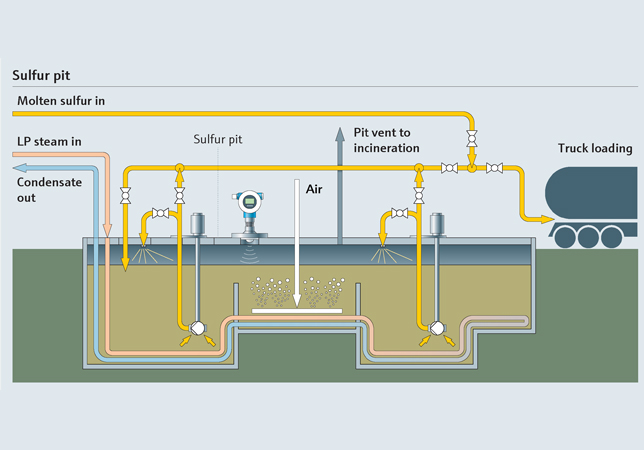

No completion date has been set for the pipeline, which is widely expected to deliver gas from the Kish gas field offshore southern Iran and the cross-border Hengam field in waters close to the mouth of the Gulf to northern Oman’s Sohar port. Oman is not yet seeking to market Iranian gas, Al Rumhy says.

Nonetheless, prospects for reaching a deal on the proposed pipeline received a significant boost in November 2013, when Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh says Oman would become the marketing centre for Iranian gas. Prospects were further raised this month as Iran and the P5+1 group of international powers appeared to advance toward a deal on Tehran’s nuclear program that would pave the way for the removal of international sanctions against Iran. Muscat is widely reported to have played a pivotal role during the often tense international talks as a mediator between Tehran on one side and Washington and Riyadh on the other.

Research fellow Kristian Coates Ulrichsen at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in the US has pointed out that Muscat’s proposed gas deal with Iran, as well as its role in the nuclear discussions, is in line with the policy established over decades by Sultan Qaboos, who he says has consistently sought to balance regional and international interests while creating room for policy movement. This policy has been further characterised by low-key implementation based on detailed, patient discussion to minimise confrontation.

The strategy has enabled Oman to maintain a certain economic and cultural distance from its oil-rich Arab neighbours, especially Saudi Arabia, while still benefiting from membership in the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council, the other members of which are Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait.

The prospect of sanctions being removed relatively quickly from Iran, a country with which Oman shares a long history of trade relations, has a number of potential consequences for the sultanate – most of them positive.

Key for Oman’s oil and gas sector is the prospect of Iranian investment in the planned Duqm refinery, deepwater port and industrial city, planned for development on a sparsely populated stretch of Oman’s coast about 300 km southwest of Muscat.

Duqm is closer to Oman’s onshore oil fields than the sultanate’s existing refineries at Sohar and Mina al-Fahal, near Muscat. It is also roughly halfway between Muscat and Salalah, the southwestern Omani port near the Yemeni border, which was in open rebellion against rule from Muscat when Qaboos took power.

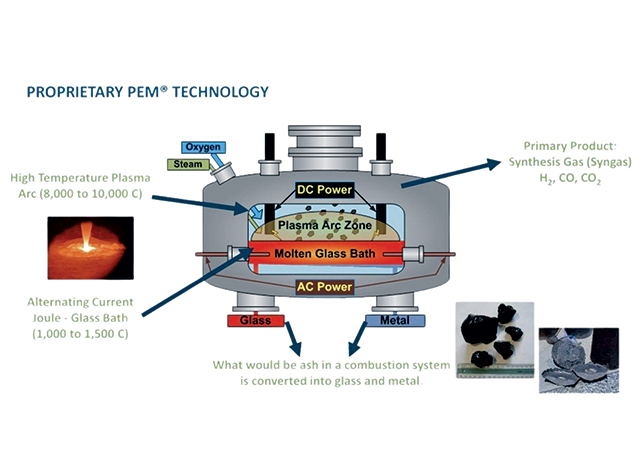

That makes Duqm arguably Oman’s most politically important infrastructure project. Economically, it is envisioned that the new port, strategically located outside the Gulf between Africa and Asia, will become a trans-shipment centre for container traffic as well as a storage and trading hub for many liquid commodities, possibly including Iranian crude.

The gas project is linked to Duqm because Muscat is seeking to make its willingness to pay for pipeline construction a catalyst for Iranian investment in the larger economic project. That is why, despite many false starts and the prospect of further delays, Omani officials seem determined that this time, however long it takes, a deal to import Iranian gas will be concluded.

Asked if Oman would still need offshore Iranian gas after the $16 billion BP-led project to develop the sultanate’s major Khazzan tight gas field starts production – currently expected in 2017 – Al Rumhy responded that too much gas would be a nice problem to have.