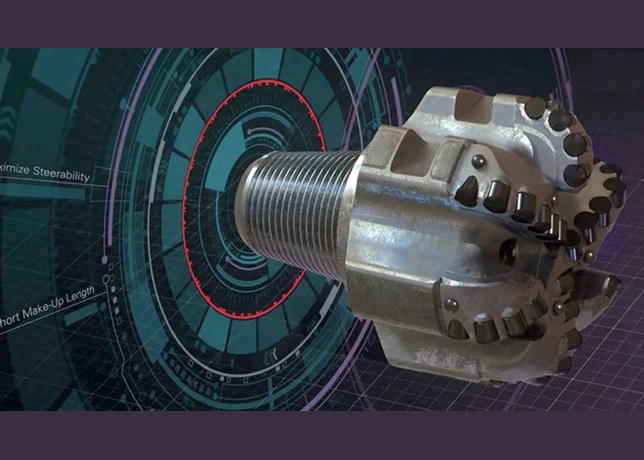

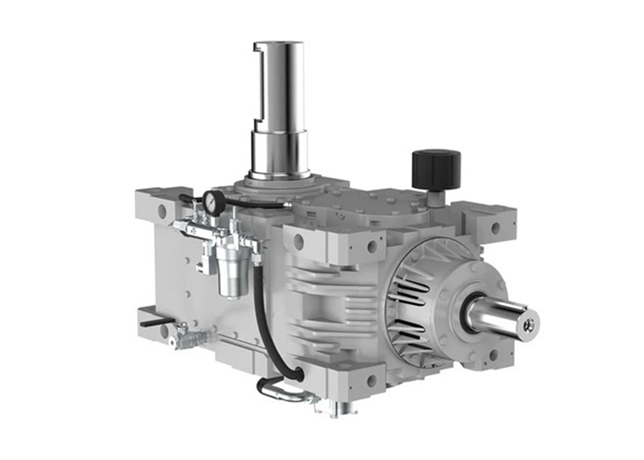

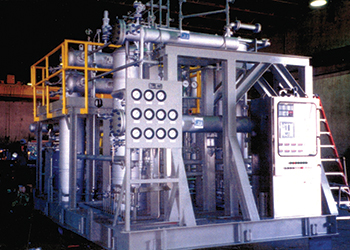

The process skid of a mini refinery

The process skid of a mini refinery

Even in China, where past governments have sought to banish the so-called ‘tea pot’ refineries in favour of larger more sophisticated facilities operated by the country’s national oil companies (NOCs), the swing has now moved into reverse

The modular, mobile or mini-refinery has been a feature of the refining landscape since the earliest days of the oil industry. However, with economies of scale pushing plant sizes in the direction of ever larger facilities over the past two decades, the small refinery has been relegated to playing only a minor role in modern refining.

But now – and for a number of quite different reasons – their time appears to have come in a number of diverse parts of the world including, perhaps surprisingly, in the US. Unrest in the strife torn areas of the Middle East and Africa effectively rule out the building of plants that can easily cost over $10 billion apiece and mini-refineries are increasingly seen as the answer to shortages of basic fuel requirements like petrol, kerosene and other refined products.

Even in China, where past governments have sought to banish the so-called ‘tea pot’ refineries in favour of larger more sophisticated facilities operated by the country’s national oil companies (NOCs), the swing has now moved into reverse. Government legislation enacted earlier this year has given the nation’s smaller operators a boost in the form of new tax and pricing initiatives.

Modular mini-refineries (which can be as small as 1,000 bpd nameplate capacity) typically have the advantage of being located close to their source of crude oil, thus minimising logistics and distribution costs. Plant modules can also be joined together to create a much larger refinery of 100,000 bpd or more, should demand dictate. This approach has already been successfully applied in locations such as Kurdistan, Indonesia, West Africa and West Siberia.

Another attraction is that mini-refineries are cheap and quick to build. A plant of less than 10,000 bpd can be built for under $200 million and in less than 18 months. This compares with the ‘mega’ Binh Dinh 660,000 bpd refinery planned for Vietnam, which comes with a price tag of up to $22 billion and will take several years to build.

RIDING THE WAVE

Examples of the new wave of mini-refineries include the 7,500 bpd modular refinery in Fujairah. In June 2014, a contract was signed between the gas cylinder manufacturer Cylingas, a subsidiary of Emirates National Oil Company (Enoc), and UK-based Pyramid Engineering to build the plant, which is expected to be ready by end-2015.

When completed, the Fujairah refinery will have a total storage capacity of 91,000 cm for handling naphtha, diesel, gas oil, fuel oil, kerosene, slop (the collective term for mixtures of oil, chemicals and water derived from a wide variety of sources) and water. Cylingas will design, fabricate, install, inspect, test, paint and commission 19 aboveground tanks and associated piping system within the new refinery terminal and the connecting pipelines to the jetty.

Meanwhile, Honeywell International reports a market for its readymade mobile refineries in war torn Iraq. The first of the company’s small, portable refinery units is being built in a factory and will be sent by sea to Iraq, trucked inland and then put down on a prepared foundation. The portable refinery is expected to be completed by 2016. When commissioned, its daily production capacity will be about 10 per cent that of a medium-scale refinery.

Honeywell is also providing modular equipment to help Pakistan Refinery (PRL) meet growing domestic demand for gasoline in Pakistan. PRL’s Penex unit will process 5,000 bpd of light naphtha. The unit is expected to start up by mid-2015.

Nigeria’s burgeoning market for mini-refineries is also being targeted by Honeywell. Last December, the outgoing government led by President Goodluck Jonathan approved the establishment of a modular refinery initiative to ease the local supply difficulties of petroleum products, especially household kerosene (HHK). Nigeria is Africa’s largest producer of crude oil, and currently has four refineries, with a combined nameplate capacity of 445,000 bpd. However, they are generally in a decrepit state and for many years have operated at well below optimum capacity. In 2002, the federal government attempted to rescue the situation by granting licences to private investors to build 18 full-scale refineries. But to date not a single one has been built and the pressure is now on the incoming government of President Buhari to make the construction of mini-refineries a top priority.

SECURITY ISSUES

However, while the proliferation of mini-refineries can be a cheap and resourceful way of tackling fuel poverty, in those regions of the world where it is endemic the technology’s simplicity and accessibility enables it to be placed out of reach of the central authorities and in the hands of smugglers and rebels.

Such is the case in the parts of Syria and Iraq that are controlled by Islamic State (ISIS) and where the existence of rebel-held mini-refineries is thought by some to have lengthened the conflict. At its height, ISIS was believed to control up to 30 mini-refineries.

Last year, much of this network was destroyed by a series of US-led air strikes that in one single day last September neutralised 12 ISIS refineries. By November 2014, Amos Hochstein, Acting Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs at the US State Department, announced that the coalition had in fact managed to wipe out a total of 22 ISIS mini-refineries, thereby shutting down around 11,000 bpd of the group’s refining capacity. US Central Command said at the time: ‘These small-scale refineries provided fuel to run ISIS operations, money to finance their continued attacks throughout Iraq and Syria and an economic asset to support their future operations.’ Illegal small-scale refineries are also thought to operate in parts of Nigeria, where they feed into the nation’s thriving black market.

NEW US POSSIBILITIES

Although mini-refineries are accused by some of helping to prop up illegal regimes, the US Congressional Research Service points to the new possibilities in North America that are emerging from the rise in production of light-sweet crude oil from unconventional resources, such as North Dakota’s Bakken and Texas’ Eagle Ford formations.

The simplest – and most suitable configuration for a mini-refinery – is a topping plant, which consists only of a crude distillation unit and probably a catalytic reformer, and is used to provide gasoline. This compares with the more sophisticated ‘crackers’ and coking refineries. Most of the refined product demand in the US is for gasoline – whose sales account for nearly 50 per cent of demand, compared with distillate whose sales account for less than 30 per cent of product demand. As a result, mini-refineries now have a golden opportunity.

Some of the new mobile units under construction in the US are little more than crude oil condensate stabilisers, costing less than $1 million. For example, the ‘skid-mounted’ 2,500 bpd crude oil condensate stabiliser that is now operating in the Texas Eagle Ford shale play cost roughly $400,000 (exclusive of tanks, pipelines, and pumps) when it was purchased in 2012.

The smallest new refinery in the US, though, is the 20,000 bpd refinery in North Dakota, which began operations in May this year at a reported cost of $350 million. The US Congressional Research Service reports that there as many as 20 other refining projects (with a total capacity of more than 900,000 bpd – an average of 45,000 bpd per refinery) that are either proposed, or are in various stages of development. These range from splitting and stabilisation plants for processing crude oil condensate to ‘tea pot’ or mini-refineries. This dash to construct mini-refineries is a clear reflection of the changing upstream landscape in the US as a result of shale oil and gas, and the change in profile of its refining sector.

Until the commissioning of the North Dakota refinery, the last refinery to be constructed in the US opened nearly 40 years ago, in 1977. Indeed, since the mid-1980s, some 150 US refineries have closed as part of an industry-wide consolidation. In order to keep up with increasing demand, the remaining refineries have had to expand their operational capacity by 23 per cent.

New resources such as North Dakota’s Bakken and Texas’ Eagle Ford formations have revitalised some refinery operations that formerly depended on imported light crude oil, thereby making the smaller refineries more competitive with large refineries that process more widely available heavy-sour crude oil.

While the new entrants into refining may find steep competition with existing operators, the cost of admission is comparatively small when processing light-sweet crude oil or condensate. Furthermore, while small refineries in the US face many of the same economic, market and environmental factors that affect large refineries, they may also benefit from exemptions in complying with certain federal regulations, such as the Renewable Fuel Standard. The greatest potential opportunity for small topping or hydro-skimming refineries are in the mid-continent region (North Dakota, Colorado) to process these new sources of light sweet crude.

Other opportunities may lie in installing condensate splitter and stabiliser plants to handle North Dakota and Texas expanding production of light sweet crude oil and condensate.

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Despite optimism in the US, mini-refineries in Africa and the Middle East – where they are being touted as rivals to the more established large-scale refinery configurations – face some acknowledged challenges.

The main disadvantage is the quality of the products. The sulphur content of gasoline and diesel can’t meet international standards if the sulphur in the crude oil is high. This is a major drawback even in African and Middle Eastern countries that are under global pressure to upgrade the quality of their fuel product. In addition, the ratio of crude oil to gasoline and diesel may be low if there is no catalytic cracking and hydro-cracking process.

But for the proponents of modular refineries there is simply no realistic alternative. They argue that for those that lack the basic fuel requirements, mini- or modular refineries are – at least in the short term – an obvious solution to the otherwise dire and unacceptable problem of fuel shortages.