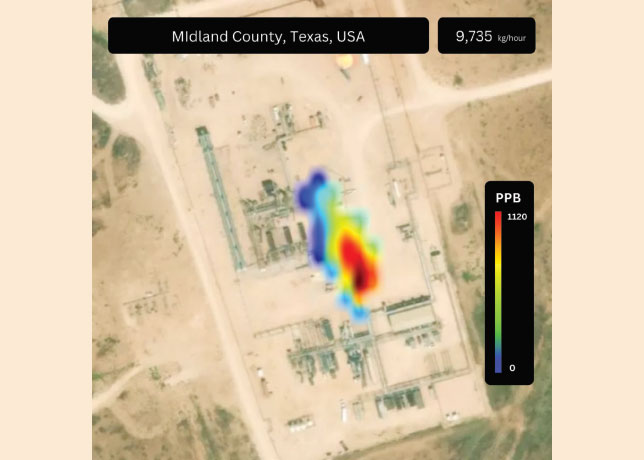

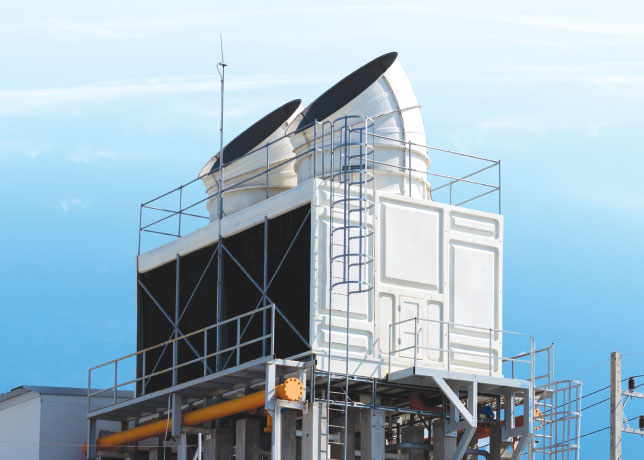

CCS facilities help reduce greenhouse gas emissions

CCS facilities help reduce greenhouse gas emissions

A comprehensive policy approach, including incentives and stronger regulatory frameworks, is essential to overcome challenges and accelerate CCS deployment, says a global report

The global shift towards decarbonisation has gained significant momentum over the past few years, with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology increasingly recognised as a vital tool for achieving net-zero emissions.

As part of this growing recognition, countries are taking proactive steps to establish and enhance the policies, regulations, and fiscal mechanisms needed to deploy CCS at a large scale, says a report on ‘CCS Policy, Legal and Regulatory Review’ by the Global CCS Institute.

This includes introducing carbon pricing mechanisms, emissions trading systems (ETSs), and offering direct funding and fiscal incentives to accelerate the development of CCS projects.

Over the past two years, there has been a marked acceleration in efforts to support CCS worldwide. Key trends include growing fiscal incentives, increased regulatory certainty, enhanced regional and international collaboration, and a heightened focus on carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

The report provides an overview of the progress and challenges facing CCS governance regimes, highlighting global and regional trends in policy, legal, and regulatory developments.

This includes a deep dive into four key regions: the Americas, Europe, Asia-Pacific (APAC), and the Middle East and Africa, all of which have seen varying degrees of activity and development in CCS deployment over the past two decades.

REGIONAL HIGHLIGHTS

• Americas: North America has emerged as one of the most mature regions in terms of CCS development, with the US and Canada leading the charge.

In the US, CCS policies have been significantly strengthened in recent years, with notable improvements in fiscal incentives such as tax credits and direct funding.

For instance, the US government has allocated billions of dollars to expand CCS infrastructure, and the ongoing commitment to the Carbon Management Challenge (CMC) further underscores the country's focus on using CCS to meet its net-zero targets.

As of 2024, the US federal government is working on finalising regulatory frameworks for offshore storage and CO2 pipeline transportation, while also releasing joint policy statements aimed at enhancing voluntary carbon markets.

At the state level, US states have begun to take more proactive roles in implementing federal CCS policies. Numerous state-specific laws have been passed to facilitate the deployment of CCS, addressing aspects such as CO2 transport, storage, pore space ownership, and liability.

In Canada, similar support exists, with the federal government introducing Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfDs) and establishing an Investment Tax Credit (ITC) in 2024.

These measures complement an increase in the national carbon tax. Brazil is also emerging as a regional leader in South America, having passed the Fuels of the Future Bill, which establishes obligations for operators of geological storage sites and creates a momentum for CCS development across the continent.

Trinidad and Tobago has made history as the first country to receive funding for CCS projects from the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

• Asia-Pacific (APAC) and India: In the Asia-Pacific region, countries are beginning to recognise CCS as essential for meeting ambitious decarbonisation goals.

Southeast Asia and Australia, in particular, are considered prime candidates for CO2 storage in geological formations, given their significant capacity and cost-effectiveness for CO2 storage.

As a result, private sector companies have started forming alliances to develop cross-border CCS value chains, involving countries like Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Malaysia.

Cross-border CCS projects face unique challenges, particularly due to international treaties like the London Protocol, which governs offshore CO2 storage.

While countries such as South Korea, Japan, and Australia are signatories to the Protocol, non-contracting parties like Malaysia and India are still working towards a clear framework for international collaboration.

Issues such as liability allocation, verification requirements, and the operation of emissions trading schemes must be addressed to ensure the successful deployment of CCS across borders.

Despite significant progress in countries like Australia and Indonesia, other APAC nations such as Malaysia, India, and China face significant gaps in regulatory frameworks.

These gaps are most apparent in areas like post-closure liability, pore space ownership, site selection, and long-term monitoring.

Financial incentives to support CCS investment are also underdeveloped, with unclear tax incentives and inconsistent eligibility criteria for CCS credits under emissions trading schemes.

• Europe: The European Union (EU) has long been a leader in the push for decarbonisation, and CCS has been a key element of its climate strategy since 2009.

The EU’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030, followed by its target to reach net-zero by 2050, has provided a strong foundation for CCS policy development.

In 2024, the EU launched the Industrial Carbon Management (ICM) Strategy, setting a target of capturing and storing or utilising 450 million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2050.

This ambition has led to greater collaboration across European countries, with increasing bilateral agreements for the transportation and storage of CO2 across borders.

In the UK, a vision for a competitive carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) market was unveiled in December 2023, aiming for the capture of 20-30 million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030.

However, unresolved issues such as the integration of bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) and direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) remain, as well as uncertainty over the inclusion of CDR in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

Despite the progress, challenges persist within the EU, including unresolved aspects of bioenergy with CCS and the future role of CDR in the EU ETS.

The European Commission is expected to address these issues in forthcoming legislative proposals, as well as supporting the development of a regulatory framework for CO2 transport and storage across borders.

• Middle East and Africa: In the Middle East and Africa, while CCS projects have been contemplated for decades, progress in policy and regulatory frameworks has been slow.

However, recent developments suggest that the region is starting to accelerate its efforts.

The UAE's state-owned energy company, ADNOC, has been a pioneer in CCS, launching a CO2 injection well for sequestration in Abu Dhabi’s carbonate saline aquifer.

This builds on ADNOC's existing carbon capture facility, which captures up to 800,000 tonnes of CO2 annually.

South Africa has also demonstrated an interest in CCS, with the World Bank initiating a capacity-building programme back in 2009.

Over recent years, the urgency of global decarbonisation has led to greater momentum in the region, with 12 out of 32 countries in the Middle East and Africa incorporating CCS or CCUS in their decarbonisation policies.

However, many countries in the region still lack comprehensive CCS legal and regulatory frameworks.

Oman is one of the few countries in the Middle East working towards establishing a CCS-specific framework, while other countries rely on existing oil and gas legislation or concession agreements to govern CCS activities.

Challenges also remain regarding cross-border CO2 transportation, as only a limited number of Middle Eastern and African countries are signatories to the London Protocol.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, while there has been significant progress in carbon capture and storage (CCS), several challenges remain. The key obstacles include:

• The slow development of legal and regulatory frameworks in many regions outside the US, Canada, the EEA, Australia, and the UK. Although some Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern countries are exploring CCS frameworks, this often lacks urgency, causing delays.

• The lengthy permitting processes for storage facilities, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) noting it can take up to 10 years to establish operational facilities. To meet 2050 climate targets, permitting timelines must be shortened, but without compromising thorough reviews.

• The management of long-term stewardship and liability for CO2 storage. Clarity on the responsibilities after the operator’s lifespan is vital to mitigate risks and attract private investment. There is no universal model for this, though some jurisdictions allow liability transfer to competent authorities.

• The commercial viability of CCS, as most projects rely on government support. Regulatory certainty, stable revenue streams, and innovative business models could improve commercial feasibility, but high upfront capital costs remain a barrier.

A comprehensive policy approach, including incentives and stronger regulatory frameworks, is essential to overcome these challenges and accelerate CCS deployment.

By Abdulaziz Khattak