Iraq’s maximum production capacity is around 5 mbpd

Iraq’s maximum production capacity is around 5 mbpd

Iraq government’s plan is to increase oil production capacity to 6.5 mbpd by 2022. To reach this target, a stable relationship with Kurdistan and other regional players and an attractive investment climate for oil companies must be created

With output of around 4.4 million barrels per day (mbpd), Iraq, the second largest oil producer in Opec after Saudi Arabia and holding the world’s fifth largest proven crude oil reserves, suffers from a lack of investment in its oil and gas fields and infrastructure, analysts say.

The country has been constrained by years of regional conflict and up until recently a downward trajectory in oil price, leaving many fields underdeveloped and new discoveries unexploited.

While Iraq’s neighbours may be taking the headlines at the moment – following Donald Trump’s decision to unilaterally withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal and the ongoing conflicts in Syria and Yemen – a number of key political events since the Iraqi federal government’s victory over Islamic State (IS) in December 2017 look set to shape the future of the country and its vital oil industry.

Most recently, the Sadrist party, led by populist cleric Muqtada Al-Sadr, has claimed a surprise victory in the Iraqi federal elections. A poor turnout of less than 45 per cent was equally surprising given the groundswell of criticism from the people of Iraq of systemic corruption and a failure of oil revenue to trickle down to the people.

It is not yet clear how the new coalition will reshape Iraq’s relationship with the US and Iran, but the escalating tension between the two is likely to lead to a period of uncertainty for investors in the country, in particular international oil and gas companies.

|

West Qurna is responsible for almost 800,000 bpd |

Another challenge of the relationship is that with the semi-autonomous region of Kurdistan, in northern Iraq, and in particular the sharing of revenue from oil and gas exports from the region.

A major failing of past governments has been the inability to ratify a nationwide oil and gas law. The subject of oil and gas rights in Iraq (more particularly, who has the authority to grant rights to produce oil and gas) has been hotly disputed since the enactment of the Iraqi Constitution in 2005.

The ensuing confusion allowed the Kurdish regional government to seize the initiative and grant numerous production sharing contracts to international oil companies, despite intense and sometimes litigious objections from the federal government of Iraq.

One only need look at the list of the oil companies present in Kurdistan, including US heavyweights ExxonMobil and Chevron, Spain’s Repsol and Russian companies Gazprom and Rosneft, to appreciate that the region represents an attractive investment proposition with comparatively generous terms compared with the risk service contracts offered by the Ministry of Oil in Baghdad.

However, the relative stability enjoyed by the Kurdistan region of Iraq was upset significantly by the decision by Kurdistan’s government to hold a referendum in 2017 on Kurdish independence from Iraq. While there was an overwhelming will of the people to form an independent nation, the vote had no legal effect and federal Iraq moved swiftly to assert its authority.

Firstly, domestic flights were banned from landing in landlocked Kurdistan and then Iraqi forces and government-backed militia reasserted control of strategically important Kirkuk, and has since entered into an agreement with BP to boost output capacity from the oilfields in the Kirkuk region. The Kurdish government had occupied Kirkuk since 2014.

With the reannexation of Kirkuk by Baghdad, Kurdistan’s oil output has almost halved overnight, and with it the revenue from that field. The full impact of the subsequent squeeze on Kurdistan’s budget and public spending is not yet clear, but outbreaks of violence in the region are becoming more common and investor confidence is low.

|

Around 1.4 mbpd of production comes from the Rumaila oilfield |

In a move to increase foreign investment in the Iraqi upstream oil and gas sector, this April saw the Iraqi Ministry of Oil hold the fifth licencing round since Iraq reopened its oil and gas sector to foreign investments in 2009.

However, while two companies from China and one from the UAE were granted blocks, several international oil companies which expressed interest in the auction (such as Total and ExxonMobil) decided not to bid, in a move that reflects continued concerns with the new Iraqi petroleum contract model.

This follows Shell’s announcement in 2017 that it would withdraw from the supergiant Majnoon field, with Petrofac and Chinese company Anton Oilfield Services having signed an Integrated Field Management Support agreement to assist the government in the continued operation the field.

Iraq’s maximum production capacity is around 5 mbpd (reduced in compliance with the Opec production reduction accord), although the government’s plan is to increase this to capacity to 6.5 mbpd by 2022. To reach this target, a stable relationship with Kurdistan and other regional players and an attractive investment climate for oil companies must be created.

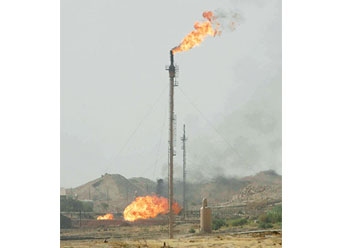

Years of fierce battles with terrorists and a prolonged internal sectarian strife has meant that Iraq’s oil revenues-reliant economy has not just suffered financial damage, but the oil and gas industry itself has severely borne the brunt of conflict.

Today in Iraq, the oil belt in the north, whose control the military recently claims to have wrestled back from an extremist group, is almost in a dilapidated state; the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region continues to operate in defiance of Baghdad, having established its own parallel oil sector; and investments from international oil companies and other global stakeholders is under jeopardy due to the critical security situation.

To put this into context, capital investments have been broadly deferred in recent years, with field expansions on hold and large-scale infrastructure projects delayed on the back of the security situation. Militants continue to pose a threat to exports from northern Iraq and northern exports are reliant on the Kurdistan export pipeline and the Iraq-Turkey pipeline.

As such in general, safety is of paramount concern for oil and gas institutions in Iraq with the lack of capital investment being the major impediment to growth,' says Ehsan Khoman, director, Head of Research and Strategist for Mena at MUFG.

Safety is and continues to be of paramount importance for the development of the oil and gas segment and especially for the international oil and gas players in Iraq. Many of the IOCs have expressed apprehensions about the need to hire private security to safeguard their assets and workforce and this definitely adds to their costs and not to forget the challenge in attracting workforce (towards the energy sector) in Iraq,' believes Vinod Raghothamarao, director consulting, Energy Wide Perspectives, at IHS Markit.

According to one such security consultancy firm –Al Murabit Security Services, which provides the full range of security and risk management advisory in Iraq for IOCs, oilfield service companies and infrastructure development players – the concept of HSE assumes a whole new meaning in the country. Oil and gas (sector) has led the way in health and safety, which in places like Iraq, becomes HSSE – Health, Safety, Security and Environment,' Simon Barry, director of Al Murabit Security Services, states.

To be fair, environment is not a major issue in the eyes of many Iraqis at the moment. Security can be like HSE; going through the motions to tick a number of boxes, or actually designing and providing a service that enables people to get things done with a minimum of risk. It is the application of security, and at times its control and oversight, that often affects activity and growth, not the need for security itself. The bottom line is whether it is treated as a commodity or as a critical enabler,' Barry says.

Despite the many adversities, Iraq unarguably has withstood the test of resilience to remain a prominent oil producing nation in the world, and a formidable stakeholder in the global energy market. The country’s output is estimated to be about 4.5 mbpd at present, with estimates suggesting that output level could touch 5 mbpd by the end of the year. More than 80 per cent of the production comes from the southern region. Around 1.4 mbpd of production comes from the Rumaila oilfield, while West Qurna is responsible for almost 800,000 bpd.

The rest of the output comes from the oilfields of Majnoun, Zubair, Halfaya, Missan, Gharraf and Badra, with about 500,000-700,000 bpd coming from the North, where Kirkuk is the key contributor.

The security risk that the situation poses to life, limb and industrial operations has been repelling a number of foreign players, causing Iraq to lose out on investments it desperately needs to bolster its upstream sector. The few IOCs that remain are reportedly content with simply continuing operations without disruptions, and not planning expansion of their activities in the country.

Among others, three oil majors, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and Lukoil invested in Iraq,' Ehsan Ul-Haq, director – Crude Oil and Refined Products, at London-based Rescource Economist Ltd, says in retrospect. BP operates Iraq’s largest field, Rumaila, Lukoil operates West Qurna 2, running at around 400,000 bpd and Shell operates Majnoun, which is producing a little over 200,000 bpd. There is also an agreement on the Halfaya field, operated by PetroChina, where the third development phase was put on hold in 2014, but will now move ahead to double production to its target of 400,000 bpd. In the North, Kurdistan has invited several companies to invest in its territory.'

The situation concerning foreign investment into Iraq is going to improve soon if the government’s ambition to invite IOCs to bid in a licensing round for nine key oil assets is realised. According to reports, a number of the blocks on offer contain trans-border fields which are shared with Iraq’s neighbours, Kuwait and Iran.

While in recent history there has been limited appetite between the neighbours to seek to jointly develop blocks as unitised fields, Iran and Iraq are reported in Q1 2017 to have signed an MoU for the development of certain joint fields and facilities, including the Sindbad and Naft Khana blocks.

'The oil industry has changed significantly in the past five years. In short, we have moved from a sellers’ market to a buyers’ market and Iraq faces a lot more competition from other regional emerging markets and other emerging oil and gas regions (whether it be Africa, Asia, the Eastern Med, deep water, the Arctic, etc),' Jason Rosychuk, a senior associate at law firm Pinsent Masons, remarks.

'Of course, the largest challenge has come from unconventional sources. Giant fields, such as in the Middle East, boast development budgets in the billions, with lead times of around five years. So IOCs have many more options to consider now than they did a decade ago. In terms of Iraq, most development is in line with stated goals of the IOCs and the government to increase oil production on the producing fields, so these development projects have continued,' Rosychuk says.

His advice to Iraqi oil authorities: 'Iraq would be well served by not focusing on the supermajors, as they tend to have done in the past, and tailor their licencing rounds to independent and junior companies. This is because the smaller companies tend to dedicate more care and attention to proving up the assets, as the value to the company of any particular asset is much higher. The Kurdistan region was very successful with this approach.'

Despite several impediments, Iraq still stands tall as one of the major oil producers and exporters in the world today. However, the country reportedly faces a lack of economically-viable natural gas resources to develop, which has resulted in Baghdad having to import gas from countries like Iran.