Eni ... showing interest in Iraq’s upstream

Eni ... showing interest in Iraq’s upstream

As has been the case elsewhere in the region, Asian companies driven by a different set of priorities have helped offset the decline in Western interest. But the shift raises serious questions about the future trajectory of Iraq’s oil output

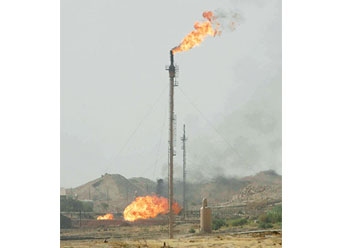

Western oil majors have been rethinking their investment priorities as tight oil and deepwaterfields have emerged as competitive alternatives to low-cost, but low-margin Middle East resources. In Iraq, tough fiscal terms have left them indifferent to big new upstream projects, in sharp contrast to the situation 10 years ago when they were clamoring for access to the country’s giant southern fields. As has been the case elsewhere in the region, Asian companies driven by a different set of priorities have helped offset the decline in Western interest. But the shift raises serious questions about the future trajectory of Iraq’s oil output. The oil ministry has just signed six new technical-service contracts (TSCs) for exploration and development blocks awarded in the country’s fifth upstream licensing round in April. Brought forward to two weeks before Iraq’s May 12 parliamentary elections, the hastily convened auction failed to attract bids from any of Iraq’s major upstream operators, except Italy’s Eni. Instead, the main winner was Crescent Petroleum, the United Arab Emirates-based independent that has close links to Iraq and gas interests in the Kurdistan region. Blocks also went to little-known Chinese firms Geo-Jade Petroleum and United Energy Group. The signing ceremony followed the finalisationof another TSC — with China’s military-backed ZhenhuaOil — to develop the East Baghdad oil field. It also comes as Chinese state-controlled majors PetroChinaand China National Offshore Oil Corp. push ahead with plans to raise output at the Halfayaand Missanoil fields, respectively. Integrating their operations with affiliated oil-field service companies has helped the Chinese majors to make their investments in Iraq more profitable. And with their cheaper labourcosts, Chinese oil services firms have generally found themselves in great demand, winning contracts at other major Iraqi upstream projects lately, including Majnoon, the giant field that Royal Dutch Shell will formally relinquish this month. The need to secure future energy supplies from a top Opecproducer is undoubtedly a key strategic consideration for Asian firms that have strengthened their ties with Iraq. That is clear from the partnership that Zhenhuaformed with state oil marketer Somoto sell crude to China and import oil products. The acquisition of Royal Dutch Shell’s stake in the West Qurna-1 field by Japan’s Itochu for $406 million provided another clear example of this strategy. Jogmec, the state-owned Japanese firm providing 40 per cent of the financing for the Shell-Itochu deal, says its participation in the field’s development would contribute to stable oil supplies for Japan. The ministry is putting a brave face on the results of what was Iraq’s first bid round since 2012. After the six new contracts were signed, it indicated that production from the blocks could reach 500,000 barrels per day. But the fact remains that, despite some notable improvements in the contract terms, top-tier companies with deep pockets were absent and five blocks received no bid. Furthermore, aspects of the new TSC reveal a persistent strain of resource nationalism. The maximum net revenue share—the sole bidding parameter—is subject to a 35 per cent tax, and was set at less than 8 per cent for three of the bid round’s most prospective blocks. Meanwhile, certain costs will no longer be eligible for recovery and at least 95 per cent of the operator’s in-country staff must be Iraqi. Nevertheless, given the country’s enormous potential, some big foreign players continue to closely monitor upstream opportunities in Iraq—perhaps more so now that renewed US sanctions have effectively placed Iran out of bounds.