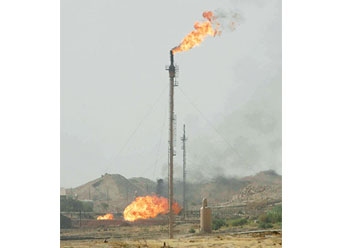

About 255,000 bpd of capacity remains shut in, mainly at the Avana dome and Bai Hassan oil fields

About 255,000 bpd of capacity remains shut in, mainly at the Avana dome and Bai Hassan oil fields

The ministry of oil’s refusal to publish data has thrown doubt and uncertainty over how much Iraq is currently producing. In January, the last month in which the ministry published detailed figures, state oil company production amounted to 4.224 mbpd

Under the Opec/non-Opec production agreement struck in November 2016, Iraq was given an allocation of 4.35 mbpd. However, it has never fully complied with that reduction, producing and exporting as much as it can.

Rising oil prices, over compliance by other Opec members, including the more than 500,000 bpd fall in Venezuelan output over the last 12 months, have masked the lack of Iraqi compliance.

Meanwhile, renewed US sanctions on Iran, which will come into effect later this year after US President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal in May, are also expected to provide room for other Opec members with spare capacity – primarily the Arab Gulf states – to increase production. The Opec/non-Opec deal currently runs through end-2018, when the renewed US sanctions are expected to kick in.

The ministry of oil’s refusal to publish data has thrown doubt and uncertainty over how much Iraq is currently producing. In January, the last month in which the ministry published detailed figures, state oil company production amounted to 4.224 mbpd.

KRG production after the loss of the Avana dome and Bai Hassan field in October 2017 to federal control was about 336,000 bpd, including 286,000 bpd exported to Turkey and 50,000 bpd supplied to the Kalar refinery in Erbil. This means total Iraqi production was 4.56 mbpd, rather than the 4.36 mbpd quoted by the ministry. Since January, 50,000 bpd has been added from the Avana dome of the Kirkuk oil field to NOC production.

|

Northern Iraqi production capacity in total would rise to just over 1 mbpd by 2022 |

The official ministry rate for KRG production in January was just 136,000 bpd , but KRG exports to Turkey were recorded at 267,000 bpd — an obvious anomaly.

Taking into account the estimated production of fields in Kurdistan, domestic refinery requirements, and the figures for exports of Iraqi crude from Turkey’s Mediterranean port of Ceyhan, KRG output is in reality about 350,000 bpd. This means that total first-quarter northern production averaged 570,000 bpd. Add this to central and southern production and Iraq is currently producing as much as 4.63 mbpd.

After the Iraq National Energy Strategy (INES) was published in mid-2013, the Iraqi cabinet adopted a mid-range scenario of reaching 9.0 mbpd by 2020, excluding Kurdistan. That remained the official target until April 1, 2018, when a new one of 6.5 mbpd for the whole country was adopted as part of the government’s approval of the new five-year Economic Development Plan (2018 –2022).

In this period, the KRG is assumed to double production from 350,000 bpd to 700,000 bpd. However, this is unlikely to be achieved. The KRG’s current production rate is likely to be sustained for the next two years, rising steadily to reach 400,000 by mid-2020 and 450,000 bpd by 2022, significantly less than the 700,000 bpd assumed in the five-year plan.

|

Central and southern production capacity is expected to rise to 4.53 mbpd by end-2018 |

Current NOC production is around 220,000 bpd, but it has capacity of 475,000 bpd. This output is used to supply local refineries and power stations around Baghdad. About 255,000 bpd of capacity remains shut in, mainly at the Avana dome and Bai Hassan oil fields. There has been no outlet for this oil since the suspension of federal exports via the KRG export pipeline to Ceyhan. The shut-in capacity will remain redundant until a new agreement is reached between Erbil and Baghdad.

The federal 2018 budget law states that the KRG should commit to the export of 250,000 of federal oil before the federal government will release funds due to the KRG under the current budget. This would require the marketing of Ceyhan exports by the State Oil Marketing Organisation, settlement of debts with the KRG, payment for pipeline operations and a new deal on export volumes with Turkey. Other alternatives—rebuilding the Iraqi leg of the old ITP line, and/or increasing local refining capacity – remain years away.

Both sides agree that the current situation is unsustainable and have made conciliatory noises. A deal may well be struck by year’s end after the formation of new governments, following elections in May. If so, northern exports could reach 600,000 bpd by end-2018 or early 2019.

By then, NOC production would be 475,000 bpd, 170,000 bpd from currently producing fields, 275,000 bpd from Avana and Bai Hassan and 30,000 from other rehabilitated small fields. This can be expected to rise to 550,000 bpd by 2022, owing to further development of Bai Hassan. As a result, northern Iraqi production capacity in total would rise to just over 1 mbpd by 2022.

|

Ratawi has proven reserves of 2.5 billion barrels |

Production from the southern and central areas of Iraq now has to be deduced by subtracting KRG and NOC output from the country total. In first-half 2017, the figure was 3.81 mbpd, in the second half 3.91 mbpd, and, in first-quarter 2018, 4.055 mbpd, based on the detailed data published in January by the ministry of oil and realistic estimates of KRG output.

By adding the estimated production of the central and southern oil fields contracted to the IOCs alongside those managed by the state, current production capacity of the sector is 4.060 mbpd. The southern and central regions are thus producing at full capacity.

The oil ministry keeps pressing international contractors to increase production capacities. They appear happy to oblige, following the settlement of outstanding debts in early 2017 and subsequent prompt payment of quarterly dues since then. This has been helped by higher oil prices, which result in reduced quantities of equity oil being allocated to the contractors.

As a result, central and southern production capacity is expected to rise to 4.53 mbpd by end-2018, as 200,000 bpd of new capacity is added at both Halfaya and Zubair, 50,000 bpd at Rumaila and 20,000 bpd from smaller fields. This will then increase to 4.55 mbpd by end-2020 and 4.65 mbpd by end-2022 as more capacity comes on-stream.

By 2022, total Iraqi production capacity could be 5.65 mbpd. The question then becomes, how much oil can Iraq export to international markets?

Exports from Iraq’s southern Gulf terminals averaged 3.284 mbpd in 2017, with an all-time record being set in December at 3.535 mbpd. During first-quarter 2018, the export rate averaged 3.456 mbpd. Oil available for export from the central and southern fields was slightly higher at about 3.555 mbpd. Total export capacity is 3.6-3.7 mbpd, leaving little room for further increases. These will depend post-2018 on making the system more reliable and investing in additional capacity.

Urgent projects include the completion of the sea line to the KAA terminal, replacing the ageing two sea lines to ALBOT and eventually rebuilding KAA and extensively rehabilitating ALBOT.

However, of most importance is completion of the onshore Fao terminal, which needs an additional 16 storage tanks of 58,000 cubic meters each and 10 units for the main gas turbine-driven pump house. The Fao terminal is years behind schedule and without its completion, southern export capacity will not rise any further than the current maximum of 3.6-3.7 mbpd. At present, Fao is not expected to be completed by 2022, unless the government provides more funds, which it may be able to owing to higher oil prices.

Nonetheless, production curtailment of around 300,000 bpd is likely from early 2019, assuming domestic demand of 630,000 bpd and total country production of 4.53 mbpd. It also means that plans to expand production capacity are likely to be delayed to avoid growing volumes of redundant production capacity.

Curtailment is usually applied to state-managed oil fields first. When it affects IOC fields it becomes very expensive as the IOCs are contractually paid for what they can produce rather than what they do produce. Curtailments during 2011-2014 cost the country an estimated $14 billion, as well as depriving the state of additional export revenues.

These major tasks in the south, together with the Common Sea Water Supply Project (CSWSP), are known as the Southern Integrated Infrastructure Project (SIIP), the total cost of which amounts to tens of billions of dollars.

The ministry of oil has been in protracted negotiations since 2015 with an ExxonMobil-led consortium, which includes China’s CNPC. Two under-developed southern fields, Ratawi and Bin Umar, were assigned to the consortium under favorable terms to pay for the costs of the SIIP.

Ratawi has proven reserves of 2.5 billion barrels and is expected to produce 200,000 bpd when developed. Bin Umar has reserves of 6.4 billion barrels and could sustain 450,000 bpd of production.

However, no agreement on development was reached by the deadline month of February 2018. The reason given was disagreement over the estimated base production potential of the two oil fields. Negotiations continue. A senior ExxonMobil executive met with the oil minister in early April.

The CSWSP aims to provide treated and pressurised water for injection into the southern oil fields to enhance reservoir pressures, thereby sustaining oil production and allowing increases in output. It is a vital project. It would draw water from Khor Al Zubair, north of the Iraqi port of Um Qasr, treat it and then distribute it to the major fields of the south.

The project has been under discussion internally and with various contractors and investors for nearly a decade. It is expensive, initially priced at $12 billion based on capacity of 10 mbpd of water. The project scope has now been changed to two 5 mbpd phases, each costing $4-$5.0 billion.

Owing to the delay in reaching an agreement with the consortium on the terms of implementing the SIIP project, and due to its importance for maintaining and increasing southern oil production, the oil ministry sought and got cabinet approval February 27 to re-assign the project from BOC and offer it as a private rather than state-managed investment.