.jpg)

Saudi Aramco ... cutting costs

Saudi Aramco ... cutting costs

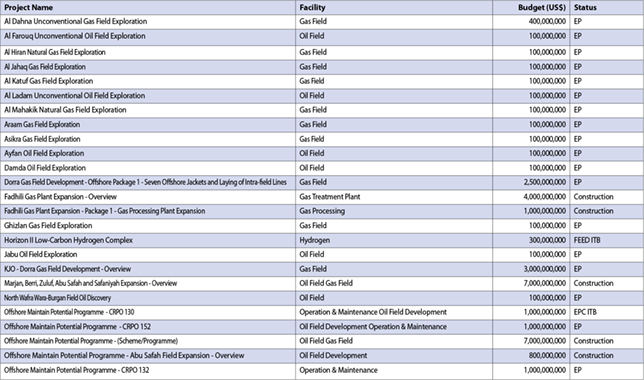

Aramco has pushed back by a year plans to build a $2 billion clean-fuels plant and put on hold deepwater oil and gas exploration and drilling activities in the Red Sea because their profitability is now in question

Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil company of Saudi Arabia, and the world’s leading producer of crude oil, is looking for ways to cut costs everywhere, from delaying key projects and pushing contractors for better deals on oilwell services to negotiating discounts on its phone and power bills, sources say.

The company is also considering slashing its future spending on production and exploration by as much as 25 per cent, much like private oil companies, sources say. However, on the downstream side, Saudi Arabia is investing heavily and developing captive markets to enter global oil market domination and counter the threat of US tight oil.

'Like everyone else, we’re using the downturn as an opportunity to sharpen our fiscal discipline,' Aramco president and chief executive officer Khalid Al Falih said in public remarks during the World Economic Forum in Davos.

'We’re cutting on a few things that we could cut, but we’re as committed as ever to our long-term strategy.' The measures demonstrate some of the risks the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) took when it decided in November to forsake its traditional role of cutting production to boost prices.

The Saudi-backed decision has hurt big, publicly listed companies, such as Royal Dutch Shell and Chevron, but is now ricocheting and hitting national oil companies.

The measures are a departure for Aramco, which had boosted its spending on pumping oil and launched its first efforts at deep-sea production when crude was regularly trading at more than $100 a barrel from 2011 to 2014. The price of Brent crude, the world benchmark, has nearly halved since June.

|

Al Falih ... using downturn as an opportunity |

The cuts don’t appear to be as deep as those after the mid-1980s price crash, when Aramco and others laid off thousands of workers and cut back production to historically low levels.

Aramco executives are considering slashing production and exploration spending to $30 billion a year from $40 billion while oil prices remain low, according to sources.

Aramco has joined oil companies, big and small, in pushing aggressively for discounts from its contractors, seeking rebates from telecommunications providers and power suppliers, for example, according to executives.

In December, the Saudi oil company summoned oil services companies including Baker Hughes, Halliburton and Schlumberger to its offices in the north-eastern city of Al Khobar to ask for discounts of up to 20 per cent on certain services, for instance, well-testing procedures, according to sources.

The companies do about $6 billion a year in business with Aramco combined. Baker Hughes offered a small discount, but Aramco has held out for 20 per cent, according to sources. The two parties were still in talks to find a common ground, but no contracts had been cancelled, they say.

Aramco has pushed back by a year plans to build a $2 billion clean-fuels plant and put on hold deepwater oil and gas exploration and drilling activities in the Red Sea because their profitability is now in question, sources say.

Geologists have estimated that Saudi territory in the Red Sea could hold the equivalent of more than a third of the kingdom’s known oil and gas reserves, but these reservoirs are also much more expensive to develop than onshore.

Deep-water projects worldwide typically need $53 a barrel to break even, according to Norwegian energy consultancy Rystad Energy.

The cost of operations in the Red Sea, a new area for Saudi Aramco, was around $1 million per day, say sources.

'It is related to budget cost reduction in the Red Sea offshore,' says one of the sources.

Deepwater exploration in the Red Sea had stopped because of several factors, including environmental issues, costs, and the need for further studies to minimise risks.

'One of the most expensive offshore (areas) happens to be in the Red Sea – the depth is different from the Gulf coast. They did discover a lot of oil and gas but they need to do lots of tests. Now with the current prices, they have put it on hold until further notice to collect more data,' says a source.

Saudi Aramco said in its 2013 annual review that it was continuing operations in the Red Sea’s deep waters and had made a new oilfield discovery at Al Haryd.

'It would not be surprising if Saudi Aramco were to suspend exploration in the Red Sea because it is a very complex basin, and no significant discoveries have been announced since the Midyan field complex and the Um Luj condensate discoveries accomplished by the Aramco exploration team of the early 90s,' says Sadad Al Husseini, a former top executive at Saudi Aramco and now an energy consultant.

'The intention to grow market share and move away from its role as swing supplier increases the likelihood of Saudi Arabia ramping up its petroleum supplies going into H2 2015 by 0.5 to 1 million barrels per day (mbpd) and 2016, in our view,' says Miswin Mahesh, analyst at Barclays Capital.

'By building local refineries and increasing stakes in refineries globally (South Korea, China, US), Saudi Arabia has a growing captive market for its crude. It is uniquely positioned relative to other oil producers in a highly competitive market.'

Saudi Arabia is an equal partner with Royal Dutch Shell in Motiva refinery, the US’ largest refinery. The investment has helped Riyadh maintain its market share – in percentage terms – in the US, even as other Opec producers such as Algeria and Nigeria have seen their market share drop on the US Gulf Coast.

|

Profitability of Aramco’s drilling activities in the Red Sea are now in question |

The International Energy Agency predicts the Middle East will establish itself as a major downstream player, with Saudi Arabia leading the way.

'Saudi Arabia is on track to join the club of major oil-product exporters following the completion of two grassroots refineries within the kingdom and the start of a new product trading company, Saudi Aramco Product Trading Company, in 2012,' the IEA says.

Over the next five years, the Middle East will add more refinery capacity than any other region in the world, with nearly 1.7 mbpd of new capacity. It will also add 1.2 mbpd of desulphurisation capacity additions and 712,000 bpd of upgrading capacity, the IEA forecasts.

Rising Middle East product exports will have an even greater impact on global oil product markets than the transformation of the US downstream sector in years to come, with outflows coming from two new mega-refineries: Saudi Arabia’s 400,000 bpd Satorp plant in Jubail and the Yasref facility in Yanbu on the Red Sea, also 400,000 bpd.

Saudi product exports got a first boost in December 2013, when the Satorp refinery started exporting products. Net exports surged to an average 370,000 bpd in the first 11 months of 2014 from 85,000 bpd in the corresponding period a year earlier. Since then, the Yasref plant shipped its first fuel cargoes in January.

Aramco has also invested in refinery capacity in key markets of Asia, with a stake in Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Company in China, and a two-third stake in S-Oil Corp., South Korea’s third-largest refiner. Aramco is also looking to set up a refinery in Vietnam for $22 billion.

'This not only gives Saudi Arabia a captive market for its crude but also helps to channel regional refined product exports to markets where Saudi crude is finding it hard to gain market share,' the Barclays analyst says.

Last year, the country’s refined product exports rose by 262,000 bpd – up 43 per cent compared to the previous year, while production from refineries hit a record 2 mbpd.

Saudi Arabia holds 80 per cent of Opec’s spare capacity – or around 2.7 mbpd – which the kingdom could maximise. This would increase Saudi Arabia’s production at a time when its own domestic fuel consumption is rising at a rate of 2.8 per cent each year till 2020, and eating into its exports.

'If there is reduced likelihood of a sustained call on its spare capacity, given US shale barrels could return at a higher price, the kingdom could reconsider the level of spare capacity it holds and put more barrels to the current market,' Mahesh says in the report.

Meanwhile, Al Falih says oil prices have fallen too far and will take time to find a level that balances supply and demand. Saudi Aramco is reviewing its own investment plans as a result of the steep oil price fall, with some projects likely to be postponed and some contracts renegotiated.

The Aramco chief’s comments came just weeks after Saudi oil minister Ali Naimi said that the kingdom would not cut oil production, even if oil prices were to fall as low as $20 per barrel.

'I don’t think anyone wanted it to go where it has gone,' Al Falih says.

'It’s too low for everybody,' he says, referring to current price levels. 'Even consumers stand to suffer in the long term.'

Al Falih says Saudi Aramco had sufficient cash to fund its 2015 capital programme, which would be smaller than had been anticipated before the price slide but still larger than in 2013. Nevertheless, he says, the price slump meant that the company would have to re-examine its approach to a number of projects.

'Our investment will have to adjust to the realities of today. We will push some projects into the future, we will stretch some of them and renegotiate some contracts,' he says, without giving details.

Nor did he give a dollar figure for the 2015 capital budget, though he indicated that a large part of it would be directed toward natural gas development.

Al Falih says it would take time for the current global oil glut to be absorbed and for supply and demand to be brought back into balance, and that oil industry investment would 'inevitably' slow in response to the lower prices.

When asked whether Saudi Arabia would reverse its policy of not cutting output to support prices, Al Falih says that the government, through the oil ministry, had stated that the kingdom would not 'single-handedly balance the market in a downturn.'

|

Aramco ... diversifying |

Saudi Aramco will, though, continue to maintain spare production capacity so that it would will be able to increase production in the event of world oil markets being undersupplied at any point.

But for now, he says, Aramco is not seeking to increase its crude production capacity from the current 12.5 mbpd.

'We’re not really adjusting a lot; we’re already at the capacity we aspire to be at,' he says. 'But we have to have to invest a lot in gas,' he adds.

Al Falih declined to identify a price that would be healthy for the oil market and the industry, noting that in the not-too-distant past $100/b had been held up as a price fair to both producers and consumers but, in retrospect had been 'maybe too healthy' as it had helped to underpin the strong growth in oil production outside Opec.

He says lower prices offered an opportunity for oil producers worldwide to improve fiscal management.

'I think we were spoiled by $100 oil. We lost focus on fiscal discipline and that last penny,' he says. 'We could be more disciplined in our spending.' Al Falih cast doubt on the likelihood of oil prices soaring to $200/b as a result of slower oil sector investment and, as a consequence, future supply shortages, as has been suggested by some Opec and oil industry officials.

'I doubt we will be approaching that level unless the industry stops completely investing,' he says. 'We have to assume that everybody sees the long-term recovery and maintains some level of investment.'

He emphasised Saudi Arabia’s own long-term view of the oil business.

'I think what matters for us is not price or revenue at any given time,' he says.

'It’s across the cycle,' he says. 'We’ve been in this business for 82 years and we plan to be in it for a long time to come.' Unexpectedly strong growth in non-Opec supply, which is outpacing growth in world oil demand, has come from a number of areas, but in particular from the US, where the shale boom has dramatically increased domestic crude output and reduced import volumes over just a few years.

The US Energy Information Administration, statistics arm of the Department of Energy, is forecasting average crude output of 9.3 mbpd next year, almost double the 5 mbpd pumped in 2008.

In December, Saudi oil minister Naimi said that if Saudi Arabia were to reduce, production prices would go up and Russia, Brazil and shale oil producers in the US would take the kingdom’s share of the market.

Al Falih, however, rejects any suggestion that Saudi Arabia, which drove Opec’s November decision not to cut crude output, was seeking to shut down US shale oil and gas production. He noted that he and oil minister Naimi were on the record as stating that US shale output was 'needed and welcome on the global scene.'

New sources of hydrocarbons will be needed to keep the world supplied with energy during what is likely to be a lengthy transition to a global economy powered mostly by non-hydrocarbon energy sources, he says.

On the gas front, Aramco has already invested $3 billion in developing Saudi Arabia’s non-conventional gas resources and, Al Falih says, 'we’ve just earmarked an additional $7 billion.' These resources include shale.

'We wouldn’t be able to do this without the success of the US,' the Aramco chief says. 'We’re going to create our own fit-for-purpose unconventional business.'

Aramco was believed to be making profits of more than $180 billion a year, far outstripping the $33 billion of ExxonMobil, the largest listed oil firm.

The company has been spending heavily on getting into all sorts of businesses far removed from drilling for crude. Besides huge investments in petrochemicals--an obvious diversification for an oil producer--it has gone big on solar energy; and it is planning to build a shipyard, with a South Korean company.

In many of these sidelines it is acting as a vehicle of government policy, helping to diversify the economy and improve the skills of the national workforce. It is developing a new industrial city in Jizan in the country’s south-west, to boost non-oil exports. It runs Kaust, the kingdom’s first mixed-gender university. It was called on to take over from Jeddah’s local council in protecting the Red Sea city from floods. It is charged with building a cultural centre in Dammam, along with 11 sports stadiums. It runs an energy think-tank in Riyadh and a technology cluster in Dhahran.

Although the government provides the cash for some of Aramco’s nation-building projects, and the company outsources some of these to contractors, the workload of overseeing them all must surely be distracting its senior management from their core business. Yet the company continues to have new duties heaped on it, as the government’s ambitions exceed its own administrators’ capacity to achieve them.

With crude recently trading at around half of the $100-plus a barrel it was fetching a year ago, and with oil contributing over 90 per cent of government revenues and providing 85 per cent of Saudi export earnings, economic diversification has become more of a priority. Yet although Aramco must still be making sizeable profits, the weak oil price means it needs to devote more attention to its core operations.

Tighter budgets could be an excuse for Aramco to get out of some of its less fruitful sidelines, although some observers worry that it could instead cut back on projects that have the best prospects of profitability, such as solar energy. Or it could just end up being given more duties while trying to cope with lower oil prices.