.jpg)

Aramco ... set to become the first producer of shale gas in the Greater Middle East

Aramco ... set to become the first producer of shale gas in the Greater Middle East

Saudi Arabia is said to have over 1,000 tcf of non-conventional hydrocarbons, consisting of shale gas, tight gas and ultra-sour gas to find and prove

In an effort to reduce its alarmingly high domestic consumption of conventional crude oil, Saudi Arabia is to become one of the first countries outside of North America to use shale gas for power generation.

This gas-to-power (GtP) concept has become the core of the state-owned Saudi Aramco’s new strategy for domestic energy and the export of surplus electricity to its neighbours and other regions which will be connected to its power grid.

Saudi Aramco is set to become the first producer of shale gas in the Greater Middle East (GME). Its shift to non-conventional gas will enable the kingdom to free up more of its crude oil output for export to the world markets. Since 2010, Saudi Aramco has been warning Riyadh repeatedly that without this shift, the kingdom would lose its position as the world’s biggest crude oil exporter by 2028.

Remaining the world’s largest exporter of crude oil during the next decades is of major geo-political importance to Riyadh. It will help maintain its lead in Opec and its position as a key member of the G20 in which Saudi Arabia is the moderator for the global oil market, thus in charge of the world’s energy supply security. This twin role has been promoted by the US and China.

Now China is the world’s largest oil importer and main beneficiary of the current fall in crude oil prices. The Saudi-led GCC bloc in Opec is behind an oil price war against the organsation’s hawks and Russia.

Saudi Aramco is to become the largest among the world’s integrated petroleum and energy firms. It is venturing into the GtP business on a big scale, as well as expanding its capacity as producer in the kingdom’s petrochemicals sector. It is the largest oil refiner in the GCC region, having integrated refining/petrochemical JVs in the kingdom which involve large IOCs as partners.

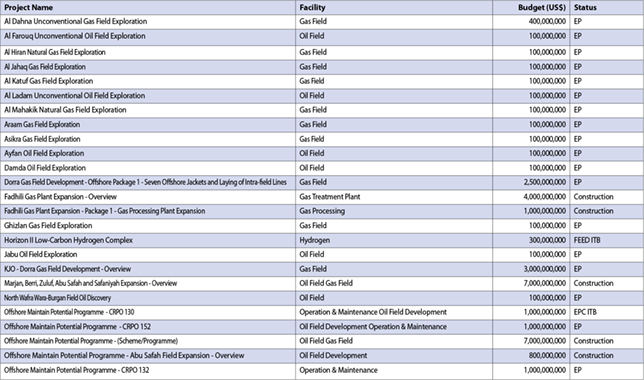

An importer of natural gas in LNG form, Kuwait is the first GCC state investing in shale gas resources in Canada and Australia being developed by major players in non-conventional petroleum. In so doing, the Kuwait Foreign Petroleum Exploration Co (Kufpec), a unit of state-owned Kuwait Petroleum Corp, hopes to transfer the most advanced shale E&P technologies to the emirate which also has important shale oil and gas resources.

Saudi Arabia is said to have over 1,000 tcf of non-conventional hydrocarbons, consisting of shale gas, tight gas and ultra-sour gas to find and prove. Alone, recoverable Saudi shale gas resources amount to 645 tcf. These exclude the proved reserves of conventional gas which amount to 286 tcf. Shale and other tight gas resources are being explored and partly developed by Saudi Aramco with the help of leading US petroleum service firms.

Saudi Aramco already is working on the shale gas deposits in the north-west close to Turaif and Jordan’s border. The company has drilled over 30 wells there. Development work will begin in 2015 and first gas will reach domestic consumer from late 2017 or early 2018. Saudi Aramco’s Phase-I production target is 200 mmcfd to feed phosphate mining and industries in the northern regions and a power plant in the south-western region of Jizan. But to produce shale gas, the cost in the initial phase would be about $8/m BTUs. Saudi Aramco will produce 15,500 mmcfday of conventional gas by 2015. That expansion of 4,300 mmcfd from the first half of 2011 will be fed by two huge offshore fields Karan and Waset.

Saudi Arabia’s demand for natural gas is growing at the rate of 7.5 per cent per annum. This is mainly due to increased demand for electricity and Saudi Aramco’s focus on GtP. Most of the current gas production is going to the power sector. The rest is used for water desalination and industry.

The kingdom’s major gas-rich shale formations (Fms) tend to be very thick layers with trapped hydrocarbons in continuous shale layers. This leaves a weaker proximity to brittle rock layers, such as limestones or dolomites, which can be fractured, propped and serve as drainage path-ways for the gas entrapped in the shales.

|

Aramco will need to develop different technical skills to capture |

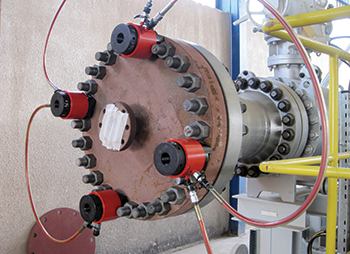

Under shale gas extraction techniques, hydraulic fracturing (fracking – high-pressure injection of water, chemicals and sand) breaks up the rock structure and allows the gas to flow more easily. In the main Paleozoic shale zone, the gas-rich one lies at the bottom of the shale Fm thousands of feet deep, into which it is particularly difficult to tap. While thinner layers of organically rich shales are available in other areas of the kingdom, these have been largely ignored due to their limited commercial value.

Even as Riyadh has mounted a geological argument for commercial shale gas production, there are still formidable technical and financial challenges to be met. The capital-intensive fracking process requires development costs to rise to tens of millions of dollars for each well. Building infrastructure for shale gas, including gathering and distribution facilities covering vast distances, will add significantly to costs.

And there is need for ample supply of water that fracking requires and which in Saudi Arabia is a major problem to resolve.

Cost is a key issue in the context of a subsidised Saudi gas market. The domestic gas sales price is capped at $0.75/m BTUs. The best North American shale play in terms of the break-even cost is $3.50/m BTUs. That shows how hard it will be to make it work commercially. The gas in Kidan, the massive Rub’ al-Khali-based sour gas field, requires a price of $6/m BTUs to make it commercially feasible.

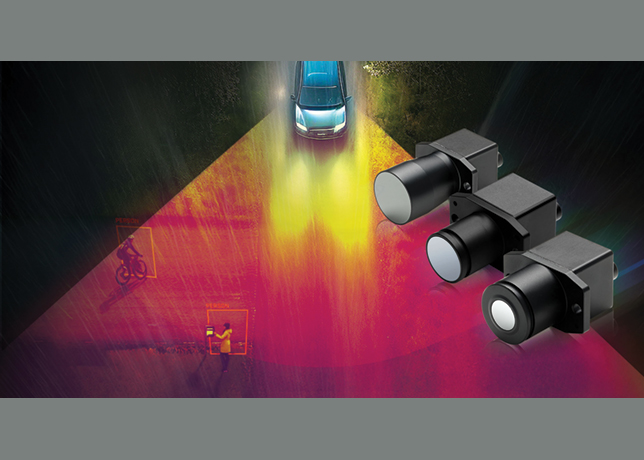

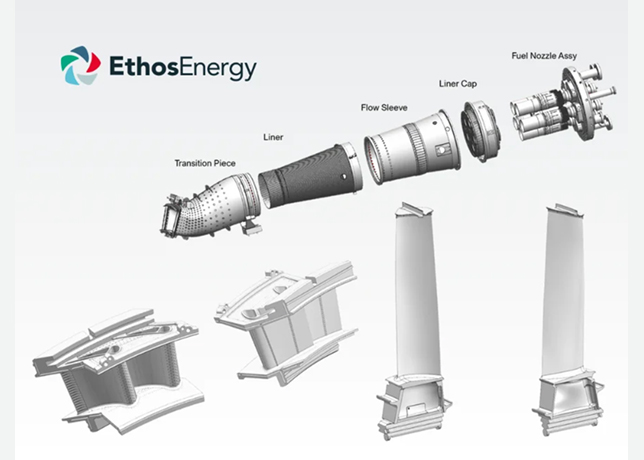

Though Saudi Aramco has built up a strong reputation in the application of technology, it will need to develop different technical skills needed to capture non-conventional gas. The cutting edge technology for shale gas is largely in the hands of specialist US companies like XTO, acquired in 2009 by ExxonMobil.

The amount of water needed in fracking is huge. While desalinated water could be used for the purpose, this is an expensive option. Another option being studied is sea-water with its salt and other contents to be treated by chemicals.

Geologists at Saudi Aramco had begun testing new petroleum sourcing theories, including the Paleozoic potentials, since the early 1980s when several interesting developments occurred in Oman and Yemen. The discovery of deep Fms, mostly Paleozoic, beneath existing fields in Oman encouraged Saudi Aramco to let geologists investigate this zone in several parts of the kingdom.

Initial attempts made south and south-east of Riyadh in the early 1980s had a negative result and the central region was declared barren. Geologists’ persistent argument about Paleozoic potentials were not only disregarded but such theories were over-taken by a fall in oil prices, a drastic cut in Saudi Aramco exploration and staff, etc. It was only in late 1986, after Saudi Aramco received precise, high-tech equipment, that another survey of un-explored areas was encouraged. By then several fields’ production capacity had dropped as a result of extensive moth-balling.

Addressing a conference held in Acapulco (Mexico) by the Riyadh-based International Energy Forum (IEF) and the International Gas Union (IGU), Saudi Petroleum & Mineral Resources Minister Ali Al Naimi said: 'in addition to gas facilities already built, we are developing several more major gas facilities, both onshore and offshore'. These will be fed from the kingdom’s 645 tcf of shale gas.

With the kingdom’s energy use expected to grow from 3.4 mbpd of crude oil equivalent in 2010 to 8.3 mbpdoe by 2028, Saudi Aramco has been looking to use its natural gas resources to support growing demand. Electricity use has been rising at 7.5 per cent annually, adding to the already large demand in the kingdom. In 2011, Naimi noted, Saudi electricity demand amounted to 7,420 kWh per capita. That was more than three times as high as in Mexico, despite having similar total levels of consumption.

Despite Saudi Arabia’s intentions to double its gas production in the next decade, the kingdom does not plan to export any of it. Naimi said: 'Saudi Arabia currently has no plans to export its gas or get into the LNG business'. But he added that this did not signal a lack of Saudi interest in the international gas market. He explained: 'It is clear that different forms of energy are becoming more closely integrated than ever before. Integrated in terms of prices and in terms of the movement of resources around the world'.

Naimi then gave critical insight into a rapidly expanding sector of Saudi Arabia’s already large energy industry. Even though the kingdom does not plan to export any of the new natural gas production, the increased use at home could have major effects on Saudi Arabia’s energy industry.

|

Oman is the first GME country to develop its non-conventional gas reserves |

The IEA recently said that, with natural gas currently providing around 43 per cent of Saudi Arabia’s electricity, the bulk of domestic demand is met through a combination of fuel oil and diesel. By increasing its natural gas production to meet its growing domestic energy demands, the new shale-based projects would have important ramifications to the global energy market.

The Saudi Ministry of Petroleum & Mineral Resources and the Supreme Council for Petroleum and Minerals have over-sight of the oil and natural gas sector and Saudi Aramco’s operations.

Saudi Arabia is the largest consumer of petroleum in the GME, particularly in the area of transportation fuels and direct crude oil burn for power generation. Domestic consumption growth has been spurred by the economic boom as a result of historically high oil prices during 2000-13, and large fuel subsidies.

The North American shale gas boom has transformed the US from being the largest gas importer in the world, to a potentially huge exporter of LNG. Using the most advanced shale E&P technologies, Saudi Aramco hopes that fracking will supply it with an abundance of natural gas which can be used for the domestic power sector.

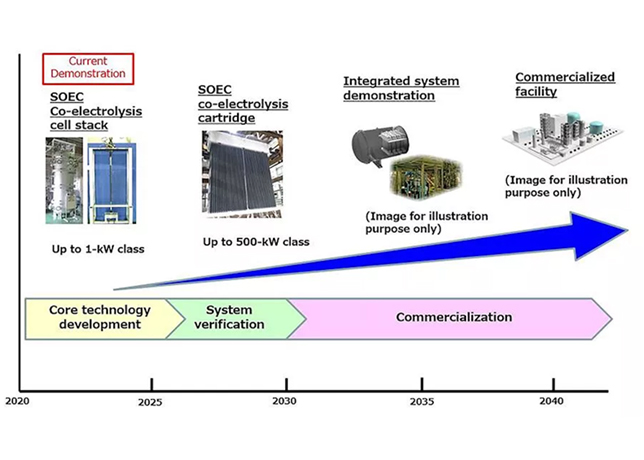

Saudi Aramco’s President/CEO Khaled Al Falih says that, by 2020 its production of shale gas would be in the range of 1,000-1,500 mmcfd. This will rise quickly to reach between 7,000-9,000 mmcfd by 2025 and could exceed 15,000 mmcfd by 2030.

Al Falih first gave Saudi Aramco’s shale gas perspective, when he spoke at the World Energy Congress (WEC), stating: 'we are ready to start producing our own shale gas' and other non-conventional gas resources in the next few years and deliver them to [domestic] consumers. He then said: 'Only two years after launching our own unconventional gas programme, in the northern region of Saudi Arabia, we are ready to commit [shale] gas for the development of a 1,000 megawatt power plant which will feed a massive phosphate mining and manufacturing sectors' in that part of the kingdom, near the border with Jordan'. But the power plant will be in Jizan, in the south-west of the kingdom.

Oman is the first GME country to develop its non-conventional gas reserves. The operator at the tight-gas fields is BP. BP’s commercial gas production is expected to begin in 2017.

Saudi Aramco has predicted that the country’s natural gas demand will double by 2030, a problem for a country which has a ban on all natural gas imports. In preparation, it is exploring for hidden reserves of shale gas and other tight-rock hydrocarbons across the vast kingdom, mapping the deposits and hoping that they will help it meet the future demand.

The shale gas set to feed the planned 1,000MW power plant project in the Jizan oil refining complex, which Saudi Aramco had in the previous years hoped to complete by 2017 is being delayed further and is likely to be completed in early 2018, with work on associated infrastructure is already behind schedule.

Riyadh believes using shale gas for domestic power production will help it to maintain the largest spare crude oil production capacity in the world, vital to protect the global oil markets from changes in production from less stable countries, and guarding against potential oil and gas price spikes that could occur as a result.

Al Falih has said that, 'as part of our drive to become the world’s most integrated energy company, we have increased our annual capital budget ten-fold from $4 billion in the past ten years to $40 billion.

In the past two years alone, he added, Saudi Aramco has swung its production by more than 1.5 mbpdoe in order to address market supply imbalances'.

(Saudi Aramco, now producing about 9.7 mbpd of crude oil, on average had in 2013 produced 11.6 mbpd of total petroleum liquids – including condensates and NGs which are excluded from the Opec output quotas).

Now, Saudi production of gas-related liquids are averaging about 2 mbpd. Total petroleum liquids production had declined 0.13 mbpd from 2012, the first fall since 2009. Saudi Arabia in 2014 has decreased its crude oil production to accommodate non-Opec production growth, mainly from the US and, to a lesser extent, Canada.

Of its 12.5 mbpd crude oil output capacity, about 300,000 bpd is Saudi Arabia’s 50 per cent share of the production in the Divided Zone (formerly known as neutral zone). Non-crude liquids in Saudi Arabia and in the other Opec countries are produced at full capacity.