Solar panels near a coal-powered power plant … the energy transition is not a story of replacement, but one of coexistence

Solar panels near a coal-powered power plant … the energy transition is not a story of replacement, but one of coexistence

Despite the push for renewables, fossil fuels will remain integral to the world’s energy mix beyond 2050 as geopolitics, and rising power demand transform energy dynamics, says a McKinsey report

The world’s energy landscape is undergoing profound transformation, yet fossil fuels are far from losing their relevance.

Despite growing investments in renewables and low-carbon technologies, oil, gas, and coal are projected to retain a dominant share of the global energy mix well beyond 2050.

According to McKinsey’s Global Energy Perspective 2025 report, fossil fuels are expected to account for between 41 and 55 per cent of total energy consumption by mid-century, down from today’s 64 per cent, but still higher than previously projected.

This persistence underscores how complex and uneven the global transition remains, driven as much by geopolitical uncertainty and policy shifts as by the relentless rise in energy demand.

The energy transition is not a linear story of replacement, but one of coexistence.

Even as renewables, nuclear, and storage technologies advance, fossil fuels continue to underpin energy security, affordability, and industrial growth across the world.

With developing economies rapidly industrialising and populations expanding, power demand is increasing faster than clean technologies can scale.

As such, the global energy transition will remain a balancing act; between ambition and reality, and between decarbonisation and development.

THE FORCES RESHAPING GLOBAL ENERGY

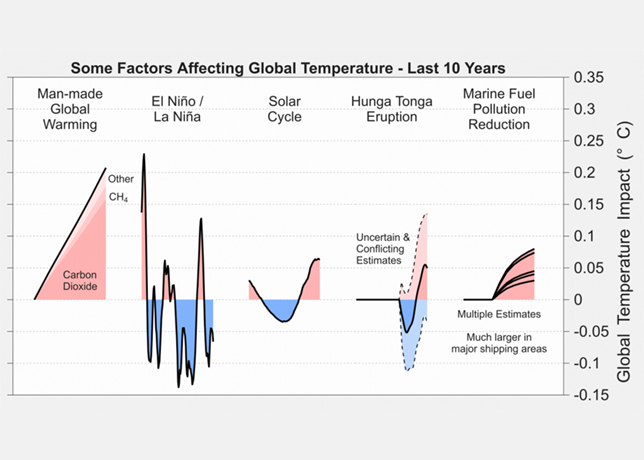

Geopolitical volatility is now one of the most decisive factors shaping global energy outlooks.

The shocks of the past few years—from trade tensions and tariffs to energy supply disruptions—have forced governments to recalibrate priorities.

Many are now placing energy affordability and security above strict adherence to Paris Agreement timelines.

This shift has been particularly visible in Europe, where the European Commission’s Clean Industrial Deal seeks to reinforce industrial resilience through clean technology, and in Japan, whose Seventh Strategic Energy Plan integrates cleaner energy goals with supply stability.

While these efforts align climate action with national security, they also highlight the growing complexity of policymaking in an increasingly fragmented world.

Recession risks and inflationary pressures further complicate the outlook.

The report warns that a potential 2027 recession could lower global GDP by 6 per cent by 2035, slowing energy demand growth but also constraining investment in decarbonisation.

In this environment, energy diversification becomes as much an economic imperative as an environmental one.

Natural gas, with its lower emissions profile and availability, has emerged as the "bridge" and, in many regions, a "destination" fuel.

In one of three scenarios for how a transition to a system of lower carbon energy could play out, global gas demand for power generation is projected to grow at 2 per cent annually through 2050. This is a 50 per cent increase over today’s levels, and will be led by the US and Russia.

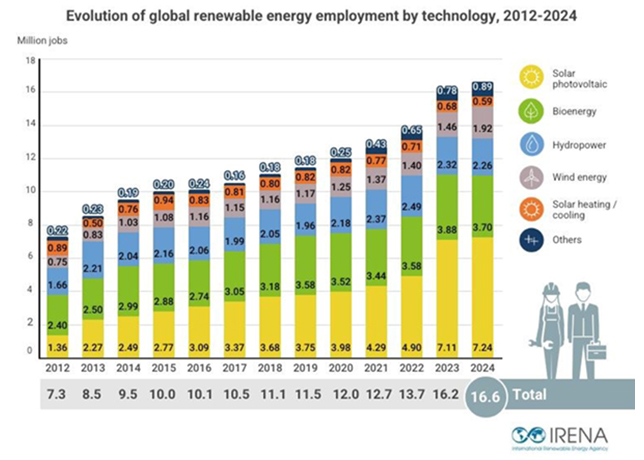

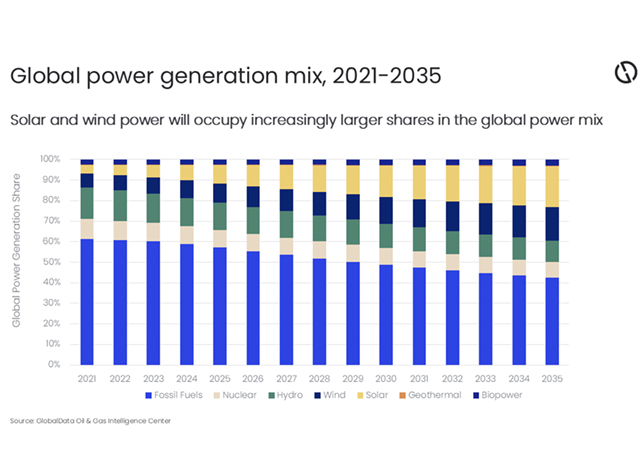

At the same time, renewables are scaling rapidly but unevenly.

Solar and wind power are expected to grow nearly threefold by 2030 and more than ninefold by 2050 compared with 2023 levels, potentially providing 61 to 67 per cent of the global power mix by 2050.

Yet intermittent generation requires clean, firm power, such as hydropower, nuclear, and advanced geothermal—to ensure reliability.

Battery energy storage systems (BESSs) are rising as a crucial complement, with capacity projected to expand fifteenfold by 2050.

Still, these technologies remain capital intensive and geographically uneven, leaving room for fossil fuels to play a stabilising role in grids worldwide.

POWER DEMAND DRIVES STRUCTURAL CHANGE

The rise in global electricity demand is perhaps the most powerful force redefining the energy landscape.

Electrification is surging across all regions, driven by industrial expansion, building energy needs, and new drivers such as data centres and electric vehicles (EV).

By 2050, electricity demand could double compared with 2023, as the world transitions from fossil-based combustion to electric power across industries, transport, and households.

• Regional drivers: Less than 45 per cent of the global population currently consumes more than 80 per cent of the world’s energy.

By 2050, the greatest demand growth will come from India, ASEAN nations, and Africa, regions where GDP could double in the next 25 years.

This means the global centre of energy consumption is shifting toward the Global South, where affordability and access remain central challenges.

• Traditional demand: Historically, buildings and industrial sectors have been the primary sources of power demand growth.

Industrial electrification remains difficult, particularly for high-temperature processes that account for nearly 30 per cent of industrial heat use.

• Emerging demand: Data centres are projected to increase their global power demand by an average of 17 per cent annually through 2030. By then, data centres could account for 14 per cent of total US electricity demand.

Transportation, especially through EVs, is becoming another major contributor, as governments incentivise electrification through subsidies and policy frameworks.

These drivers underscore how electrification, though central to decarbonisation, is also intensifying the overall need for energy.

The report projects that even as renewables expand, fossil fuels will continue supplying the bulk of baseload power, ensuring system stability and cost-effectiveness.

FOSSIL FUELS IN A TRANSITIONING WORLD

The continued presence of fossil fuels in the energy mix is not merely a reflection of policy inertia but a pragmatic response to global energy realities.

Demand for oil, gas, and coal remains structurally embedded in power systems, industrial processes, and mobility infrastructure.

In a scenario, where global energy demand peaks around 2030, fossil fuels still constitute a significant portion of supply.

Global gas demand, for instance, could rise by up to 170 billion cu m by 2030.

By 2050, gas use could reach around 5,020 billion cu m, up from just over 4,000 billion cu m today.

This growth reflects not only cost competitiveness but also the limits of alternative fuels.

Clean hydrogen, for example, remains far from cost parity and unlikely to scale before 2040 without government mandates.

Similarly, sustainable fuels—both biobased and synthetic—are expected to reach about 600 million tonnes annually by 2050, primarily through regulatory measures rather than market momentum.

Oil demand, meanwhile, is projected to peak around 2030 at between 103 and 109 million barrels per day (mbpd).

Road transport will remain the largest contributor to keeping demand elevated through the next decade.

Although maritime and industrial oil use will gradually decline post-2040 as these sectors transition to gas or sustainable fuels, road transport and plastics production will sustain oil demand for decades.

Indeed, the chemical sector’s reliance on liquid fuels for plastics is projected to grow by 2 per cent annually through 2050, in line with global GDP growth.

By 2040, new upstream oil developments will still be required to satisfy global demand, especially as legacy fields decline.

Investment will increasingly flow to competitive deepwater and shale basins, expected to supply a third of global crude and condensate by that time.

OPEC and allied producers will continue to play a central role, providing more than half of total supply.

THE POWER MIX: BALANCING RELIABILITY & DECARBONISATION

The global power mix is shifting toward renewables, but fossil fuels remain essential for ensuring reliability and affordability.

Natural gas, in particular, serves as a firm, dispatchable source of power that complements intermittent renewables.

When paired with carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS), it becomes a low-emission option well-suited to transitional systems.

Regions such as Japan, the Middle East, and the US are already advancing CCUS-linked gas projects, while China and Singapore are exploring hydrogen derived from natural gas with CCUS integration.

Coal, on the other hand, is on a gradual decline—though it remains part of all future energy scenarios through 2050.

Its use will fall sharply in the US and Europe as ageing plants close but persist in Asia, particularly in China, India, and Indonesia, where economic growth and industrialisation still rely heavily on coal-fired power.

Even so, the load factors of these plants are declining, signalling a slow decoupling from coal dependence.

By 2050, more than 65 per cent of global power generation is projected to come from low-carbon sources, with China and India reaching 90 per cent and 85 per cent, respectively.

However, the transition’s cost and pace vary widely.

In non-OECD Asian countries and parts of the Middle East, abundant and low-cost gas will ensure fossil fuels remain part of the mix even as low-carbon capacity grows.

THE COST OF A COMPLETE TRANSITION

The path to complete decarbonisation remains steep and expensive.

The Global Energy Perspective 2025 report estimates that while achieving 45 to 70 per cent decarbonisation in the power sector could cost around $20 per tonne of CO2 abated, the final 5 per cent could cost up to $170 per tonne.

This steep curve reflects the challenge of replacing the last fossil-based power sources with high-cost technologies such as direct air capture, advanced bioenergy with CCUS, and long-duration storage.

A system-wide view, the report argues, could deliver faster and more cost-effective outcomes.

Redirecting investments from chasing full decarbonisation in the power sector toward other sectors, such as industry, transport, or heating, could yield greater emission reductions per dollar spent.

This pragmatic approach acknowledges the central role fossil fuels will continue to play in the world’s evolving energy equation, even as the march toward cleaner, more diversified systems continues.

The energy story of the coming decades will be one of complexity rather than absolutes.

Fossil fuels, once viewed solely as obstacles to decarbonisation, are increasingly being repositioned as transitional pillars supporting energy security and economic stability.

As nations navigate the twin challenges of growing demand and shifting geopolitics, the balance between carbon reduction and reliability will define the next chapter of the global energy transformation.

The world’s future energy mix won’t be free of fossil fuels, it will just be harder to predict.

BY Abdulaziz Khattak