ESG reporting is critical in the energy sector for mitigating risks and building stakeholder trust

ESG reporting is critical in the energy sector for mitigating risks and building stakeholder trust

From newly aligned standards to regulatory pushbacks in Europe, India and the US, 2025 is redefining how companies disclose climate and social impacts amid mounting investor scrutiny and political resistance

How much does ESG reporting finally matter when the rules, tools and incentives are shifting faster than markets can adapt?

In 2025, the global architecture of sustainability disclosure has entered a more fraught, contested terrain.

No longer a niche or side-project, ESG (or sustainability) reporting is becoming a central battleground for investors, governments, companies, and civil society.

This year has already seen new standards, revisions, regulatory retrenchments and procedural debates, with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) at the centre of the evolving framework.

As corporate emissions, climate risks and social impacts grow ever more visible, the demand for rigorous, comparable data collides with resistance in capitals, exchanges and boardrooms alike.

In June 2025, the GRI announced its new GRI 102: Climate Change and GRI 103: Energy standards, aiming to sharpen the climate-related disclosures companies submit and strengthen alignment with the GHG Protocol.

The new GRI standards include emissions disclosures, transition planning, energy use (renewable and non-renewable) and "just transition" metrics quantifying the effect of climate action on workers, communities and Indigenous Peoples.

Importantly, the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB) granted equivalence to IFRS S2 climate disclosures under GRI 102, meaning that companies using IFRS S2 can satisfy GRI’s climate-related requirements (for Scope 1-3 emissions) without duplicative reporting.

In parallel, GRI is rolling out new digital filing tools before the end of 2025 that would allow automated consistency checks of submitted reports versus the standards, bringing greater rigour to disclosure pipelines.

Meanwhile, the ISSB (under the IFRS Foundation) has had a busy year of consultations and proposed amendments.

In April 2025, it published an Exposure Draft introducing targeted amendments to IFRS S2 to ease certain climate disclosures, including optional reliefs for scope-related metrics and flexibility in applying Global Warming Potential (GWP) values in jurisdictions that mandate different values.

By July, the ISSB formalised a plan to comprehensively review 9 out of 12 SASB Standards (which were earlier incorporated by ISSB) as part of its 2024-2026 work plan, soliciting stakeholder feedback on metrics for nature, climate, human capital, water and more.

In May 2025 the ISSB deliberated on enhancing SASB standards in an exposure draft stage, though deferring final decisions to later ballots.

Its January meeting also considered biodiversity, ecosystems, human capital and methods for supporting the implementation of IFRS S1 and S2 amid practical challenges.

ADOPTION MOMENTUM CONTINUES

By mid-2025, the IFRS Foundation published jurisdictional profiles across 17 territories that are adopting, aligning with, or planning alignment with ISSB standards.

In many jurisdictions, for financial years beginning from January 1, 2025, listed issuers must disclose Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions under "comply or explain", while Scope 3 and broader climate-related disclosures are transitioning to more rigorous regimes.

In Singapore, amendments to listing rules require listed issuers from 2025 to align climate-related disclosures with ISSB, and from 2026 large issuers must report Scope 3 emissions.

In Brazil, the securities regulator (CVM) will integrate ISSB standards into regulation: Companies may disclose voluntarily from 2024, with mandatory application from January 1, 2026, and a phased assurance pathway starting with limited assurance.

Across Latin America and other regions, public and private entities are incrementally adopting ISSB frameworks in voluntary or quasi-mandatory form.

FRICTION IS RISING

In India, in April 2025, the Securities and Exchange Board (SEBI) issued norms permitting ESG rating providers to withdraw ratings if companies neglect business responsibility reports or inactivity persists, after its new chief flagged the disclosure regime as overly burdensome for industry.

More provocatively, the European Parliament in April voted to delay certain sustainability reporting rules, effectively giving negotiators more time to exempt smaller firms.

Earlier in February, the European Commission had proposed loosening obligations: Raising employee thresholds from 250 to 1,000 and postponing due diligence requirements.

And in October 2025, some 46 firms including TotalEnergies and Siemens urged European governments to abolish one flagship sustainability law to preserve competitiveness.

In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s new leadership has expressed public scepticism of ESG mandates, and a Wall Street regulator has voiced criticism of European ESG laws as overreach.

Still, a US judge in 2025 rejected a challenge to a rule allowing ESG factors in retirement plan investing, signalling that ESG remains contested ground but not entirely dislodged.

Beneath the headline shifts, deeper tensions surface around implementation, comparability, assurance and data technologies.

Within corporate circles and ESG specialist forums, practitioners complain that the pace and complexity of changes exceed the capacity of smaller issuers, especially in emerging markets.

In private intelligence reports (cited in forum leaks), some multinationals are said to be preparing dual reporting systems, one for investors under ISSB and another under local sustainability frameworks, for, at least, the next three years.

Meanwhile, in the academic and technical sphere, new machine-learning tools are being developed to map GRI and ESRS reporting indices or to parse ESG disclosure content automatically; for instance, the ESG-CID dataset or the ESGReveal model.

These tools may become critical as data volumes rise and investors demand real-time comparators.

But relying on AI and natural language processing in ESG raises risks of misclassification, opacity or "checkbox compliance", complaints from civil society warn; especially if oversight, audit and regulatory checks lag behind technical sophistication.

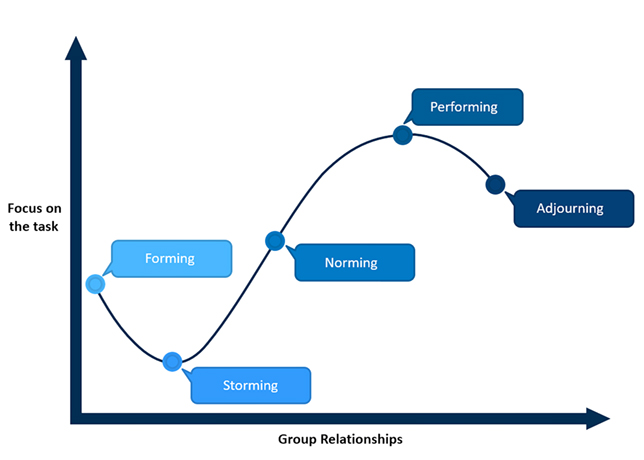

Against this backdrop, the year’s developments imply a bifurcated trajectory: Stronger standardisation at the top levels through ISSB-GRI interoperability, but increasing pressure from jurisdictions and industries pushing back or delaying enforcement.

Companies must now navigate a shifting map: Aligning with IFRS S1/S2 and GRI 102/103 (or their equivalents) while monitoring local rules that may diverge or retract.

Investor scrutiny is also intensifying, and asset managers are increasingly insisting on audited ESG disclosures or risk discounting companies.

In 2025, the challenge is no longer whether to report ESG. It is how well, with which lenses, and under what legal regime.

BY Abdulaziz Khattak