HRCs can drive a competitive supply of hydrogen

HRCs can drive a competitive supply of hydrogen

Hydrogen can play a key role in helping sectors meet climate targets, and countries rich in hydrocarbons can help build and scale the needed technology, write experts from McKinsey’s Global Energy & Materials Practice

Industry leaders are under pressure as the global climate change debate has amplified the call to limit global warming to 1.5 deg C.

In the case of hydrogen, hydrocarbon-rich countries (HRCs), including Saudi Arabia and the UAE as well as the US and Canada, could leverage their know-how and competitive reserves to scale up clean hydrogen and become industry leaders.

Most of these countries have a track record of building and scaling up global energy supply by leveraging their unique access to competitive natural resources.

According to McKinsey research, total hydrogen demand can reach 600 to 660 million tons by 2050, abating more than 20 per cent of global emissions. That said, realising this opportunity will require all relevant stakeholders to come together to develop clean-hydrogen value chains—often across geographies. Those that take decisive action in these areas will be uniquely positioned to create new sources of value and play a leading role in future global energy markets.

For the hydrogen promise to materialise for HRCs and for the market to scale, four areas will need to be addressed:

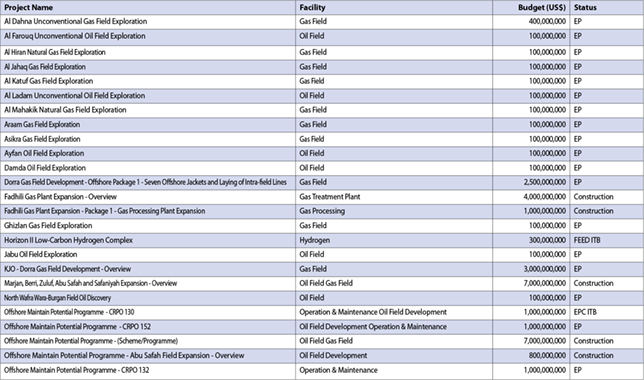

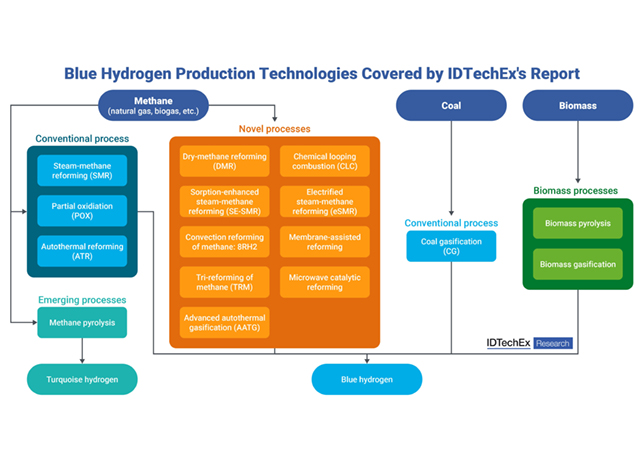

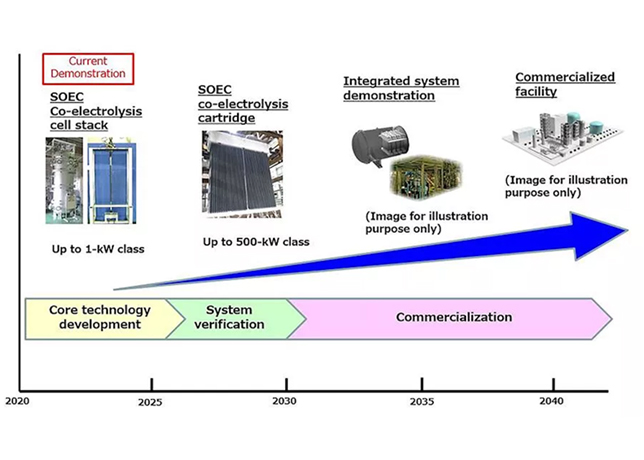

• Scaling competitive supply: This requires HRCs to scale up both blue and green hydrogen. Access to cost-competitive and abundant natural gas or other hydrocarbons coupled with technological disruption in CCUS can allow for the required decline in the cost for blue hydrogen production by 2030.

A report by the Hydrogen Council in 2021 said the cost of hydrogen for end users could drop by 60 per cent from 2020 to 2030.

• Stimulating local demand: To create a hydrogen ecosystem, there needs to be a local market for hydrogen in parallel to the development of export corridors. Governments can help by implementing the right regulatory frameworks around decarbonisation and clean air to ensure these local demand sectors start.

• Developing transportation technology: Hydrogen must be in liquid form or transformed into ammonia before it can be transported. However, liquefying hydrogen is both costly and technically challenging because it needs to be cooled down to –252 deg C, which is the lowest boiling point of any element. McKinsey analysis shows that converting hydrogen to ammonia for transport to Europe from the Middle East then converting it back into hydrogen could result in an additional cost of $2.50 to $3.00 per kg of hydrogen in 2030, which is significant, given that green hydrogen production costs could be less than $2.00 per kg by 2030 in the region.

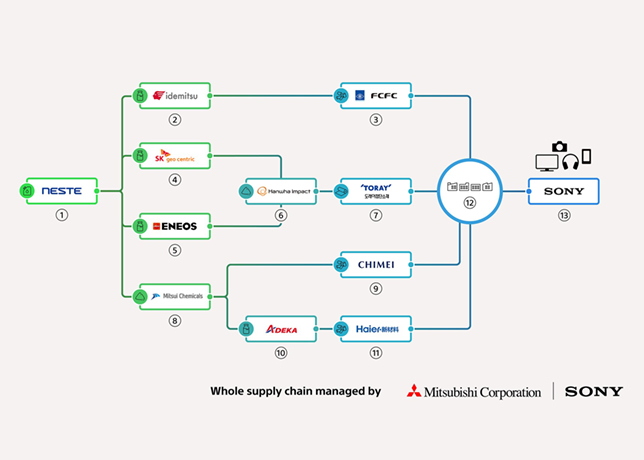

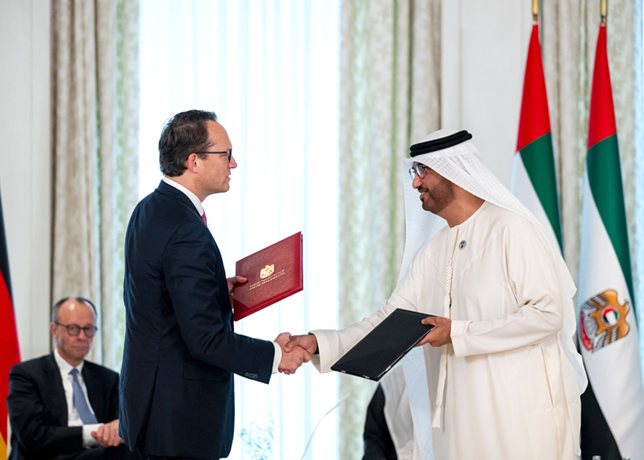

• Facilitating cooperation across value chains, customers, and countries: The clean-hydrogen value chain will require players across the stages to work together to ensure the value chain develops consistently. Partnerships could enable equipment and infrastructure developers to make investments with some minimum utilisation guarantee. Meanwhile, creating government-to-government partnerships could facilitate hydrogen flow between countries, further supporting demand uptake in target markets, and could lock in supply agreements.

ROLE OF HRCs IN THE SCALE-UP OF CLEAN HYDROGEN

Several factors are expected to drive a competitive supply of hydrogen from HRCs, including access to hydrocarbon resources, cheap renewable energy, strong domestic demand, advantaged location, and a proven track record in establishing global energy markets.

HRCs could develop and become leading suppliers of clean hydrogen by leveraging these factors, but their competitive positions may vary depending on the applicability of these factors.

To begin, HRCs are likely to supply blue hydrogen because it provides an outlet for their hydrocarbon reserves, an opportunity to (re)use hydrocarbon reservoirs and midstream infrastructure, as well as an opportunity to maintain positions of leadership in the global energy market.

Doing so requires investing in technologies such as CCUS to help ensure blue hydrogen remains competitive after 2030.

Because green hydrogen is expected to become competitive after 2030, those with access to competitive, low-cost zero-carbon energy could also build on the green-hydrogen momentum and leverage any favorable renewable-energy sources to hedge the risk of blue hydrogen’s cost competitiveness versus green hydrogen in the decades to come.

Building a robust supply of hydrogen could allow HRCs to leverage clean hydrogen to decarbonise downstream industries, such as downstream oil and gas, and chemical and energy-intensive industries, as well as long-distance aviation and marine.

HRCs could also repurpose existing gas pipelines for clean hydrogen as demand for additional infrastructure grows, helping spur investment in port infrastructure and national carriers or transport ships.

HRCs could gain leadership positions in the future hydrogen market by identifying the sources of value creation and using a number of distinct business models. For instance, Neom, Acwa Power, and Air Products have committed to invest $5 billion into an integrated power hydrogen, and ammonia production plant—including export facilities—by 2025.

At the time of publication, more than 680 large-scale projects have been announced globally, representing more than $240 billion in mature investments.

DEVELOPING THE RIGHT PLAYS IN THE VALUE CHAIN

There are six plays ideally suited for building on the competitive advantages of players in HRCs:

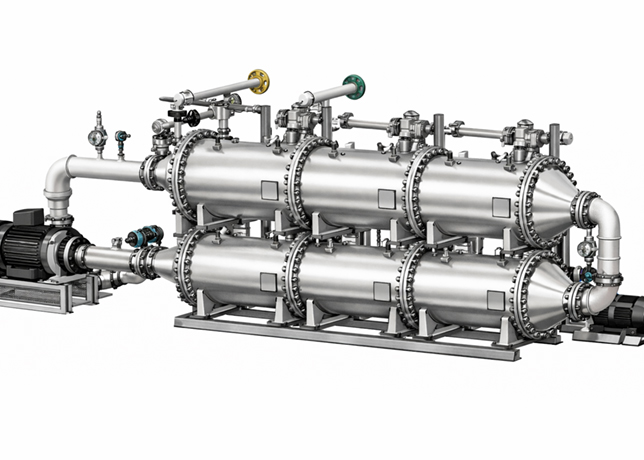

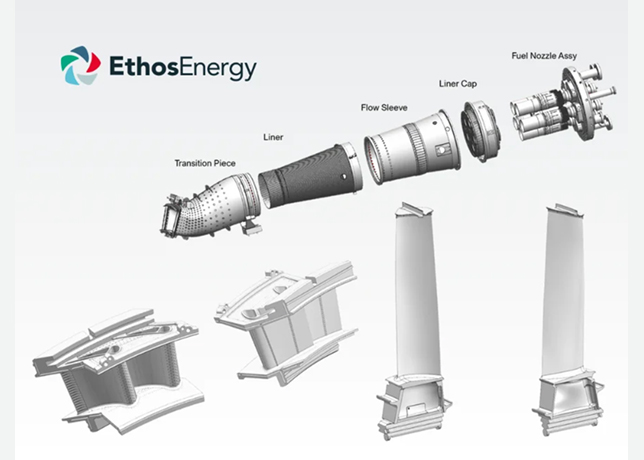

• Hydrogen equipment manufacturing: HRCs could set up a hydrogen equipment manufacturing champion to facilitate the national road map and to become a global equipment supplier. Localising manufacturing could help secure access to critical electrolyser or carbon-capture equipment in the event of potential supply-chain constrains associated with projected growth in the hydrogen economy.

• Hydrogen production: According to the Achieved Commitments scenario in McKinsey’s 2022 Global Energy Perspective, producing 600 million tons of hydrogen will require 650 billion cu m (bcm) of natural gas per year and 17,400 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity per year in 2050, which corresponds to up to 25 per cent of expected global renewable generation by that time.

Chemical companies, particularly those with significant exposure to industrial gases, such as gray hydrogen, have a majority of the capabilities and assets required to produce clean hydrogen today.

• Carbon capture, utilisation, and storage: Not only is CCUS critical for blue hydrogen production but also it offers opportunities to decarbonise operations across companies’ portfolios. In addition, captured carbon can be used in existing operations, such as enhanced oil recovery or in future products, such as synthetic fuels.

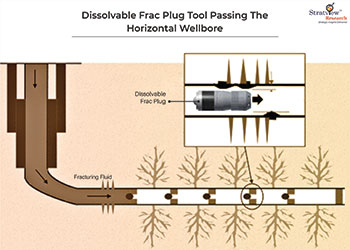

• Hydrogen transportation: To begin, NOCs can repurpose existing gas pipeline infrastructure or develop new hydrogen networks to facilitate transportation. They can also partner with ship builders to develop hydrogen carriers. A number of carriers of liquefied hydrogen will be required to facilitate a global clean-hydrogen market by 2030. In Europe, an estimated 39,700 km of hydrogen pipeline infrastructure could be installed by 2040, connecting low-cost production locations with demand hubs.

• Clean-hydrogen downstream production: HRCs with either developed downstream industry or access to cheap hydrogen could become suppliers of clean end products, such as green ammonia.

• Integrated project developers: NOCs can leverage their strong cross-value-chain positions to derisk project and downstream industries as well as their G2G relations to help secure demand.

This play is a good fit for oil companies with advantaged access to energy resources, such as hydrocarbons and green energy, as well as advantaged geography, a broad set of G2G relations in energy, and substantial local demand driven by local industries over the long term.

CONCLUSION

HRCs have traditionally played an important role in supplying the world’s energy needs. They also benefit from access to the resources required to produce green and blue hydrogen at competitive costs.

They offer a key unlock in scaling green and blue hydrogen supply and accelerating cost reductions.

Partnerships with hydrogen stakeholders in HRCs can offer companies and countries opportunities to gain exposure to the hydrogen economy and, more important, offer a path to decarbonise their respective operations and sectors.

* This article is a collaborative effort by Arnout de Pee, Partner in McKinsey’s Amsterdam office; Tarek El Sayed, Senior Partner in the Riyadh office; Joe Rahi, Partner in the Doha office; Maurits Waardenburg, an Expert Associate Partner in the Brussels office; and Mohamed Ghonima, Associate Partner in the Dubai office, where Ruchin Jain is Partner and Rachid Majiti is Senior Partner.