The corrosion-hit Motiva refinery sees return to normalcy only next year

The corrosion-hit Motiva refinery sees return to normalcy only next year

SAUDI ARABIA’S unexpected surge in oil exports to the US this year has fallen into question following a deepening crisis at the kingdom’s jointly owned and newly expanded Texas refinery. With the huge 325,000 barrel per day (bpd) crude oil unit at Motiva’s Port Arthur, Texas, refinery now expected to be out of commission for as long as a year, crippling the biggest plant in the US just weeks after the completion of a $10 billion expansion project, the Saudis are likely to throttle back US exports that hit four-year peaks in recent months.

But a deeper look at detailed import data suggests that any curbs on production may not be as deep as many expect. In fact, a Reuters analysis of government data shows that the 27 per cent jump in Saudi shipments in the first quarter was driven by higher sales to a variety of customers, not only Motiva, which the kingdom jointly owns with Royal Dutch Shell.

The world’s top exporter boosted shipments to independent refiners Valero, Marathon Petroleum and PBF Energy as part of a 300,000 bpd rise in the first quarter, according to US Energy Information Administration data. Some of that increase was due to unusually low imports in early 2011. But only about a quarter was destined for the Motiva refinery in Port Arthur, according to a Reuters analysis of more detailed data that identifies which plants consume imported oil. The increase in sales to Valero was nearly twice as large.

To be sure, the kingdom’s state oil firm Aramco must still scramble to rearrange its shipping plans to avoid surplus crude piling up in Motiva’s storage tanks or driving prices lower still by reselling excess oil, measures that are almost certain to require throttling back full-on output. An industry source in Saudi Arabia says that Motiva had reduced its orders for deliveries of crude in July but declined to give details on volume. An industry source familiar with Saudi oil policy says production “is likely to be affected”.

The bigger question is how these logistical hiccups are affecting oil policy at a higher level.

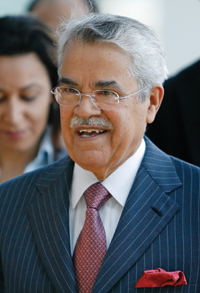

Saudi Oil Minister Ali Al Naimi has made no secret of his desire to curb $100-plus oil prices in order to provide a “stimulus” for ailing world economies, driving production this year to more than 10 mbpd, near a record high. The disruption at Motiva may also provide a useful excuse to tighten the taps without abandoning its commitment to helping restore global growth.

“Just a couple of months ago, you had people going ‘Oh my gosh, look at all this Saudi crude!’” says Jamie Webster of PFC Energy in Washington.

“A lot of it was for Motiva.... Now the question is: Are they going to find 325,000 barrels of customers elsewhere, are they going to have to bring production down, or are they just going to continue to put it in their stocks?”

In total, Motiva imported 315,000 bpd of Saudi crude in the first quarter, a 112,000 bpd increase from the year before, the calculations show. Of that, about 250,000 bpd went to Port Arthur, the plant’s largest intake since early 2007 and enough to meet nearly all the refinery’s pre-expansion demand. But shipments to Port Arthur were up only 74,000 bpd from a year ago, a relatively modest rise that is in many ways logical: Operators would have needed only a bit of extra oil in order to build up additional inventories ahead of commissioning the new units, which didn’t begin running until mid-April.

The balance of Motiva’s crude imports from Saudi Arabia in the quarter went to its Convent plant in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which had bought almost no Saudi crude a year ago. The data also shows that Saudi Arabia found other customers ready to increase purchases to a degree not previously known. Valero’s imports in the quarter jumped nearly 130,000 bpd to a total 217,000 bpd, the data show. That’s a more than 50 per cent rise over its average for all of last year, and pushed its intake of Saudi crude to the highest since 2008.

Sources familiar with Valero’s purchases says that the increase was due to a drop in traditional heavy crude supplies from Latin America and Mexico. First-quarter US imports from Mexico fell 300,000 bpd from a year ago to just 1 mbpd. Marathon Petroleum and Paulsboro Refining – a unit of independent refiner PBF Energy – also saw sizeable increases of nearly 40,000 bpd each, the data showed, although that was partly due to a particularly low base. Paulsboro’s imports are up by just over 15,000 bpd versus last year’s average.

It is not clear whether the same customers have continued to buy Saudi crude at the same rate. Most oil supply contracts are agreed on an annual basis, allowing for some flexibility in the timing of deliveries. It is also too early to assess the impact on Saudi Arabia’s production. In theory, the kingdom could seek to keep pumping at a near-record rate of around 10 mbpd, hoping to find new customers or pushing the crude into storage. But storage is running out.

“Saudi Arabia has been showing the world that it is capable at pumping at high levels of above 10 mbpd, and of course not all this oil is being sold -- a lot is going into storage,” says Kamel Al Harami, an independent Kuwaiti analyst.

Naimi says that storage inside Saudi Arabia and in its facilities in Rotterdam, Sidi Kerir and Okinawa were already full with around 10 million barrels in stock, leaving the US as a key sink for millions of Saudi barrels.

The extra Saudi shipments amount to a year-on-year rise of around 26.75 million barrels in the first quarter alone. Over the same period, US crude oil stocks rose by 28 million barrels. New weekly EIA data showed US stockpiles unexpectedly rose after two declines, pushing stockpiles back toward the 22-year highs they reached in May. Overall Saudi-US crude exports continued at unusually high levels throughout April and May, with deliveries averaging 1.54 mbpd in the six weeks to mid-June, according to provisional weekly import figures from the EIA.

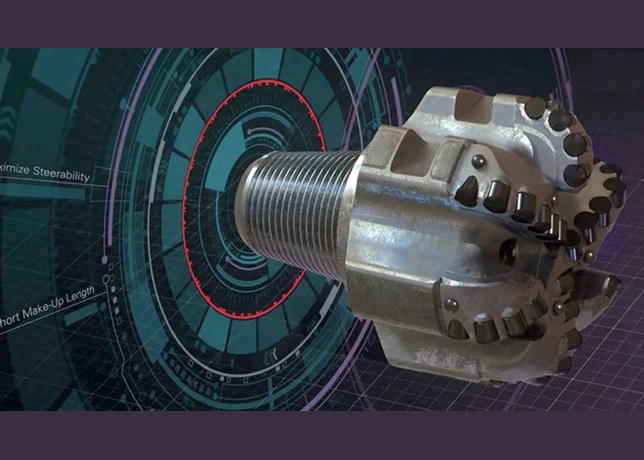

The question is how much of that oil was earmarked for the 600,000 bpd Port Arthur plant, which is now running at half-strength. In late May, as the top brass from Shell and Aramco inaugurated the $10 billion expansion, Motiva President and CEO Bob Pease said the new units were expected to run only heavy Saudi crude for about two months before diversifying supplies.

That plan was foiled within days, however, as the new crude unit experienced a glitch on June 3 that forced it to shut down. A week later, following two failed restarts, it was said to be bracing for an up to year-long shutdown.

“All of that (crude) is now going to go into storage and if you fill up storage, then it has to go somewhere,” says Chakib Khelil, an oil analyst and former Algerian energy minister.

Meanwhile, the company says that the CDU will restart in early 2013, its first confirmation of the lengthy time frame for repairing extensive corrosion at the largest US refinery.

The company did not give further details on the timing of the restart. “Normal operations will resume as soon as it is safely possible to do so,” Shell spokeswoman Kayla Macke says.

The statement comes after a month-long investigation and essentially confirms reports that the new unit – the cornerstone of its five-year, $10 billion expansion – could be out of service for up to 12 months to repair extensive corrosion.

“Preliminary inspection found that part of the unit had been accidentally contaminated with high levels of caustic (sodium hydroxide), which resulted in cracks in stainless steel piping and other parts of the crude unit,” Motiva says.

Caustics are meant to keep crude oil from clogging refinery units, but in Motiva’s unit, turned into a destructive vapour as the CDU was being restarted on June 9 following a brief stoppage for unrelated minor repairs. The refinery’s older 275,000-bpd crude unit was operating normally, Motiva says, as were all seven of its other expansion units, though some were running at reduced rates.

“Motiva is working to optimise operations without the new crude unit,” Macke says.

According to sources, a relatively small amount of caustic inadvertently seeped into the refinery’s CDU in June while workers were repairing a minor leak, unleashing an invisible but devastating corrosive agent that wreaked havoc on the plant’s heaters and piping.

.jpg)