Western Province ... providing hope

Western Province ... providing hope

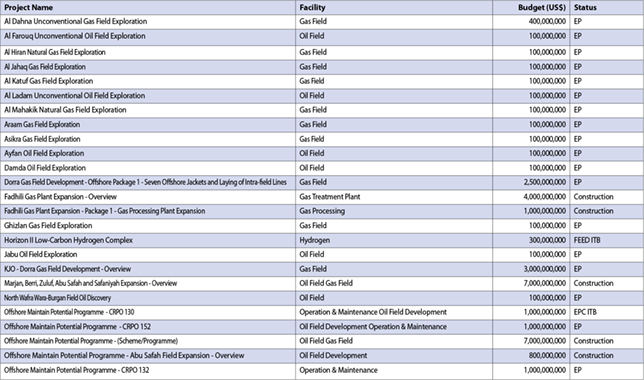

SAUDI ARABIA, which has one-fifth of the world’s proven oil reserves and maintains the world’s largest oil production of over 9.9 million barrels a day, may proceed with further underwater oil-drilling in the Western Province if seismic data supports the plan.

Saudi Arabia’s output rose remarkably in November to 10.047 million barrels a day (mbpd) – the highest level in three decades – amid recent efforts by some countries to shift to crude from the kingdom ahead of toughening sanctions on Iran. The sanctions have been imposed on Tehran over its contested nuclear programme.

The Arab world’s leading economy exported 7.704 mbpd in March, up from 7.485 mbpd in February, according to a Joint Organisation Data figures.

However, residents of the Western Region of Saudi Arabia may not be familiar with the rich massive wells, oil rigs and processing plants located across the country’s oil fields.

The majority of oil produced in the Eastern Region is loaded onto tankers and exported to the Western Province through an “East-West” pipeline that makes its way to Europe via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal.

A large quantity also runs into the petrochemicals facilities in the industrial hub of Yanbu, in Saudi’s western province.

Until recently, the Western Province had not been seen as a potential hydrocarbon hub offshore, but began to be recognised as one after Egypt made significant discoveries on its eastern coast, with about 8 billion barrels of proven reserves in its waters.

Additionally, the state oil company has several exploration findings in the Western Province dating back to the early 1990s when two small onshore discoveries were made.

“At that point we did a lot of geology, we knew there were good prospects but better offshore than onshore,” Sadad Al Husseini, a former executive vice president for upstream operations at Saudi Aramco says.

Saudi Arabia has estimated reserves of 267 billion barrels, still Saudi Aramco is constantly looking to apply more accurate seismic method before drilling a well. Aramco started surveying in the Red Sea in 2009, and now is going through a seismic data review for three years to analyze these findings.

Aramco has not released any estimates on the hydrocarbon potential in the Red Sea but its current studies have revealed a speculation that reserves under the seabed could contain as much as 50 billion barrels, which could eventually increase the kingdom’s reserves by another 18 per cent.

“I presume they got enough encouraging results from the surveys to allow them to plan for the drilling programme. There has been a lot of drilling in the Red Sea and a lot of dry holes. There is no easy oil or assurance of finding oil and gas reserves,” says Al Husseini.

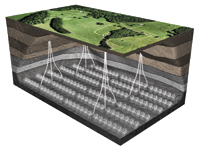

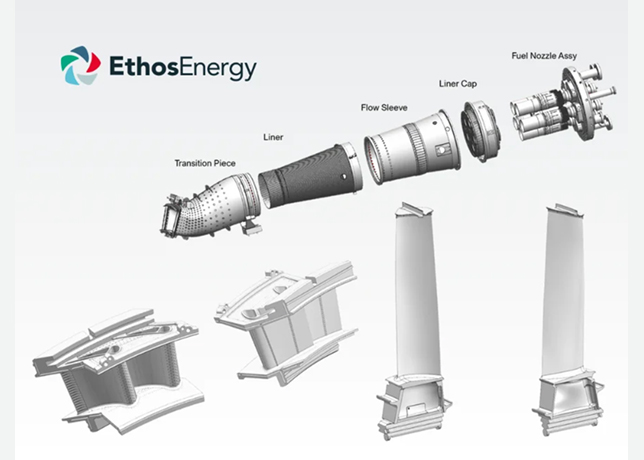

Still, exploration and producing in deep water remains a new challenge for the company as projects in the Red Sea venture requires a specialised expertise and resources to be applied in these projects. Production techniques will eventually depend on the findings. If results show a significant reservoir of crude oil, a floating rig will be used to explore a seabed as deep as 1,000 metres underwater.

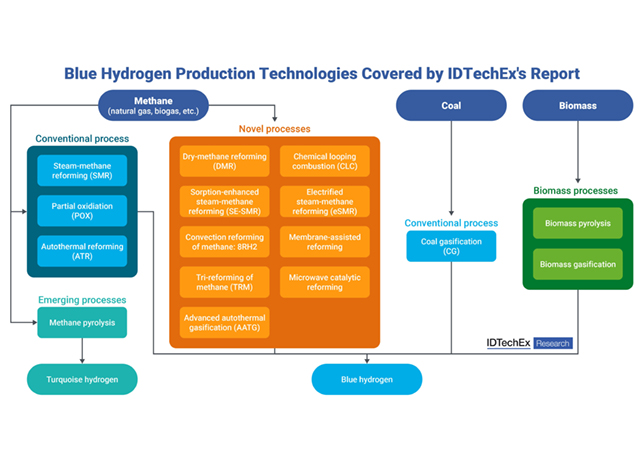

But in case the liquid fraction contains large quantity of associated gas, treating facilities would be needed to separate oil from gas.

Meanwhile, any oil discoveries would not necessarily have any immediate impact on production levels, which are already governed by Opec in accordance with market requirements and agreements. A new gas discovery, on the other hand, would present another story. Saudi Arabia holds the world’s fourth-largest reserves of natural gas, and there have been many ambitious attempts to increase its production by a third in five years.

Gas discovery in the Red Sea could potentially be a catalyst for large scale natural gas developments in Saudi Arabia, and would eventually motivate Aramco to seriously consider drilling operations in the Western Province.

.jpg)