Satorp ... first large-scale aromatics facility

Satorp ... first large-scale aromatics facility

A NEW wave of aromatics investments is under discussion in Saudi Arabia. As part of a move further into petrochemicals, state-owned Saudi Aramco is building refineries with downstream aromatics production, as well as exploring ways to add aromatics at its existing refineries.

Until now, Aramco’s refineries have only produced oil products. “For the first time, Saudi Aramco is deciding to include petrochemicals units in its refinery projects,” says Paul Hodges, chairman of UK-based International eChem. “This is moving Saudi Arabia towards more of a European/Asian/US model of petrochemicals production.”

Aramco’s first large-scale aromatics facility will be located at a joint-venture refinery and petrochemicals complex it is building with France’s Total in Al Jubail. Named Saudi Aramco Total Refining and Petrochemical (Satorp), the project will have paraxylene (PX) and benzene capacities of 700,000 tonnes per year (tpy) and 140,000 tpy respectively, and is scheduled to begin operations in the second half of 2013.

Aramco also plans to include aromatics production at refineries in Ras Tanura and Jazan, and is studying an aromatics project linked to its refinery activities in Yanbu, on the Red Sea coast.

As well as building aromatics units at refineries, Aramco is developing a petrochemicals project with US major Dow Chemical, named Sadara Chemical, and is planning an expansion at its existing Rabigh Refining and Petrochemical (PetroRabigh) joint venture with Japan’s Sumitomo Chemical. Aromatics are expected to be included in both projects.

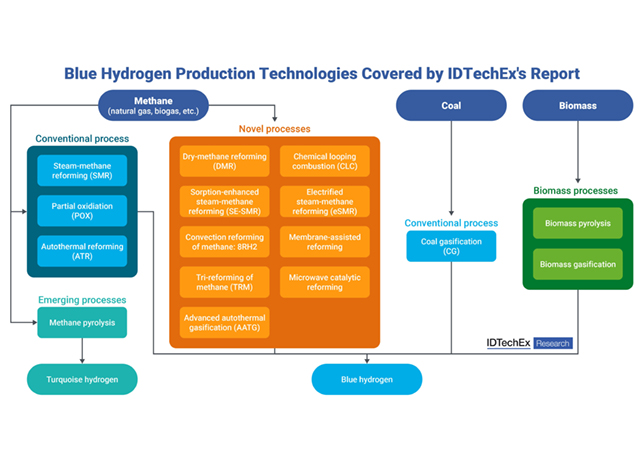

Historically, most petrochemical producers in the Middle East have focused on gas-based production to exploit the region’s cost-advantaged ethane. Only Iran has followed more of a Western model of petrochemicals production by taking naphtha out of refineries. Much of Iran’s aromatics production, however, is often diverted into gasoline, Hodges notes.

In the UAE, aromatics investments have been proposed as part of potential major new projects, such as Chemaweyaat, but nothing has been finalised.

|

The Ras Tanura aromatics plant will |

Under the original plans, Chemaweyaat was considering building an 860,000 tpy benzene unit and a 1.4m tpy PX unit.

For Aramco, partnerships with foreign players in its refinery and petrochemicals investments are providing it with the technologies and market experience it needs for its push into petrochemicals.

Aramco president and CEO Khalid Al Falih says the company was well positioned to maximise long-term value creation from its integrated activities “from the wellhead to the gas pump, and to the manufacturing of value-adding fibres, polymers, rubbers and plastics”.

He adds that Aramco, which will be a $60 billion business following the completion of the Sadara project, intends to become a “top-three petrochemical company”.

Saudi Arabia’s new aromatics production would be converted into downstream products, and then exported. Moving further downstream into new petrochemicals derivatives and end-products is part of the government’s strategy to create new jobs for the country. Two-thirds of the Saudi population is aged under 30, and youth unemployment is estimated at about three times the national average.

“Until now, there has been no rationale for investing in aromatics in Saudi Arabia, because you’ve got an engineering cost to think about, you can already sell the naphtha feedstock on a world market at a world market price and you have a freight cost to get the material to market,” says one foreign observer. “So the economics of liquid feed investments have not been terribly attractive.”

This contrasts with the economics of gas-based petrochemicals investments, “where if you don’t use the gas feed to make polyethylene (PE), you burn it,” he adds.

The new Saudi production will also face tough competition from producers in Asia, particularly China. Much of the output of these new derivatives will be aimed at China, which is becoming increasingly self-sufficient in aromatics and derivatives – particularly in the PX-to-polyester chain.

Future petrochemicals investments in Saudi Arabia will be influenced by the government’s social agenda to cut unemployment. Therefore projects with a downstream element, and hence with the potential to create significant numbers of jobs, are more viable.

The Sadara joint venture with Dow, for example, will introduce a wide range of new products, attracting downstream processing facilities and hence creating more jobs, says Hodges.

“That means that instead of exporting the raw materials, you are actually using them in the country and then exporting the finished product.”

Similarly, at its Satorp joint venture, Aramco is exploring ways to add downstream polyester projects. It has approached potential investors for a possible purified terephthalic acid (PTA) project to take PX feedstock from Satorp, an Aramco official told ICIS in July last year. The Satorp PX project and the downstream PTA project will be Saudi Arabia’s second production plants for each of these products. Sabic affiliate Arabian Industrial Fibers (Ibn Rushd) has integrated PX and PTA production at its site in Yanbu.

The move to include petrochemicals units in Saudi refineries also reflects the lack of ethane availability in the country. There have been no new licenses to build crackers in the country since 2006/2007.

There is a repositioning of the Saudi chemicals industry away from being gas-led and towards a wider feedstock slate. “Until very recently Sabic has done petrochemicals and Saudi Aramco has done oil refining and there has been no crossover,” the observer says. “Now we see Saudi Aramco going into refining in partnership with Total and Dow, which is giving them a liquid feed and getting them into aromatics.”

Adding petrochemicals to existing refineries allows Aramco to leverage its existing assets, said Fayez Al Sharef, the group’s chemicals director. Aromatics production is being considered in Yanbu, he told ICIS in December. “There is nothing certain in terms of chemicals integration [in Yanbu], but we are evaluating options. Aromatics comes at the top of the list.”

At Yanbu, the company is developing a 400,000 bpd refinery joint venture with China’s Sinopec. The project, which could come on stream in 2014, was previously known as Red Sea Refining and has now been renamed Yasref. It is part of Aramco’s plans to raise its global refining capacity to 8 mbpd over the next decade.

Aramco plans to start up an aromatics unit at its Ras Tanura refinery in eastern Saudi Arabia in 2015. The project, which is in the advanced stages of planning, will have the capacity to produce 1.1 mtpy of PX, as well as benzene, Al Sharef says. It is part of the company’s clean fuels programme, which involves recovering some of the aromatics in the refinery’s gasoline pool.

Aromatics production is also planned at the group’s 400,000 bpd refinery project in Jazan on the Red Sea coast. The project will have a combined capacity of more than 1 mtpy for PX and benzene, Al Sharef says. Commissioning is expected in December 2016.

Details of Aramco’s Sadara joint venture with Dow, located in Jubail, are still being finalised. The $20 billion project, which is expected to begin operations in early 2015, will comprise 26 manufacturing units and include production of specialty grades of PE, isocyanates, glycol ethers and amines. The majority of the output from the Sadara complex will be produced for the first time in Saudi Arabia.

The PetroRabigh expansion project in Rabigh will also bring new aromatics production. Petro Rabigh plans to widen its product slate and add 300,000 tpy of ethylene capacity. The project is expected to include a naphtha reformer – for the production of benzene and PX – and a 275,000 tpy phenol plant. Engineering contractor KBR, which is providing the basic engineering and technology for the phenol project, said last year that it expected phenol production to begin in 2014.

The new Saudi Kayan project in Al-Jubail is another example of Saudi Arabia’s diversification into new downstream chemicals projects. The 5 mtpy complex includes units for benzene and phenol. Saudi Kayan is a joint venture between Sabic and Al-Kayan Petrochemical.

While these downstream projects might not be the most commercially successful route for Saudi producers, they make sense in terms of the government’s job creation agenda. Going downstream, by using a more diverse feedstock slate, will help generate the additional jobs needed by a country with a relatively young population.

.jpg)