Steineke ... much loved geologist

Steineke ... much loved geologist

A FEW months after the signing of the concession agreement between the Saudi government and Socal, the geologists came exploring. The first two, ‘Bert’ Miller and ‘Krug’ Henry, landed at the small coastal community of Jubail, where Arab dhows lay tilted on the sands at low tide awaiting the return of the water, and a few palm trees offered meagre shade. Their arrival created as much excitement as a circus in a small Indiana town. They were strangers from a world unknown to the Bedouins – strangers who found the Bedouin’s camels and deserts equally strange.

They entered a land of rocky, gravelled soil, a flat land relieved by an occasional rocky jabal, and in September, when they arrived, the heat waves tossed mirages over the sabkhas (salt flats). Sometimes they saw a gowned Bedouin guiding his small flock of sheep or goats into the slight depressions, where they searched among the rocks for the few wisps of dried grass left from the previous winter rains, writes Phil McConnell, petroleum engineer who came to Saudi Arabia and became part of the ‘Hundred Men’, in Saudi Aramco World.

In exploring this land, the Americans, at first, travelled in what, then, we called ‘sedans.’ They were passenger cars, and since they were equipped with small tyres that sank into the sand, discouraging digging operations were frequent; back then the only roads were the long trails beaten into the sand by camel caravans. Then, in March of 1934, the exploration effort was greatly assisted by the arrival of Dick Kerr in a Fairchild plane especially designed for aerial photography.

By June, the organisation, had grown to 10 Americans, now employees of a new Socal subsidiary called ‘Casoc’. Chiefly geologists, these 10 were already prepared to recommend a location for the first wildcat, or exploratory well. They placed it a few miles from the shore of the Gulf on the flank of a jabal named Dhahran. It was the same jabal that the Americans on the island of Bahrain had observed in earlier years, causing them to speculate on the possibilities of finding oil in a land still unexplored by geologists.

|

|

King Abd Al Aziz is welcomed aboard the |

In 1935 the wildcatters – or drilling crews – came, travelling by launch from Bahrain. They came ashore at a small fishing village called Al Khobar, a few miles from Jabal Dhahran. The land they entered offered them the sand and the rock on which they stood, and the air that they breathed; beyond that they had to bring everything they needed for living and working, even, at first, their drinking water. Like the geologists before them, they were pioneers in the fullest sense of the word.

By the following April they had developed sources of drinking water, built the simple structures they required and assembled their equipment. In those days, and for a long time after, they drilled with ‘cable’ tools that dig much slower than rotary equipment, but require much less material and support for operation. They drilled throughout a summer of wind and heat and into the fall before they encountered oil; it caused jubilation in both Saudi Arabia and San Francisco, but continued drilling and testing showed too little oil or gas to have commercial value, and the rejoicing died.

The second well renewed their hope. On a short test, oil flowed from it at a rate equal to nearly 4,000 barrels per day. In San Francisco, joy again flowed with equal abundance and within a week the drillers were authorised to drill four more wells in Dammam, plus a wildcat in an area that appeared promising some 20 miles distant (32 kilometres). Fred Davies, the manager in the field, was dubious concerning the rush to start four more wells in Dammam, and suggested that operations might be pushed too rapidly. But the San Francisco office brushed aside his suggestions. Oil had been discovered! Let’s go!

But a few weeks later, when Well No 2 (closed because of lack of oil storage tanks) was reopened, it produced chiefly water -and that would be the pattern for the next two years: holes drilled into the zone (a layer of earth or rock) where showings of oil had been encountered, alternately stirring up their hopes and plunging them into disappointment. None of the holes yielded enough oil to justify operation.

At first, the management of Socal was unwilling to admit that the Saudi Arabian project might be a failure. The oil must be there – somewhere – so the company continued to send in more men and more materials. It expanded the camp at Dhahran (all oil field communities are known as camps) with permanent buildings, added air cooling (that sometimes even worked), built roads and sank water wells. Indicating their intention to create a permanent community, Socal even built family housing, and in 1937, six wives arrived to occupy those houses. By July of that year, the number of American employees had risen to 53.

But soon management began to wonder. Where was the oil of Saudi Arabia? Was this another multi-million-dollar effort that would have to be written off? It did seem so. As the months and years passed, the hopes for finding oil slowly drained away, and geologists sent to Saudi Arabia now were told that they could expect to move on to other foreign operations soon.

|

|

A Casoc party camps near Abu Jifan en |

Coincident with the camp expansion, however, the Socal wildcatters had started to drill their seventh well: Dammam No 7. It was started in December, 1936, this time to seek for oil in formations deeper than those tested by earlier holes. From the start, this effort encountered far more than the amount of trouble to which drilling wells normally are subjected. Caving rock, stuck drill pipe and equipment failures one after another, turned Dammam No 7 into a nightmare. The struggle continued for a year and a quarter. But at the end of that period, in a zone some 2,000 feet (609 metres) below that penetrated by earlier holes, they encountered oil, and on a test (even on the test, the drill pipe got stuck and was never recovered) it produced at a rate of nearly 4,000 barrels of oil daily, and, unlike Dammam No 2, that had raised their hopes briefly back in 1936, the flow from No 7 continued.

This was the first well to penetrate what thereafter was designated as the ‘Arab Zone,’ a geological layer of earth or rock, which proved to be the major source of oil in Saudi Arabia. It provided the first reliable evidence that the huge expenditures of the exploration period might be recovered – and that a dependable source of income for the Saudi Arabian government was likely.

As a result Casoc began to funnel men, machinery and money into Arabia and to set up an organisation strong enough to handle the development of these new, promising sources of oil. The result was the sudden integration of two totally different cultures – one American, the other Arabian.

The Casoc organisation that arrived in Saudi Arabia in the early 1930s entered a country in which industrialisation, according to western concepts, was hardly recognised and certainly not understood. In turn, these Americans had practically no knowledge nor understanding of the society that they were about to encounter. But though the collision of two radically different social patterns presented an excellent opportunity for conflict, wisdom and restraint prevailed as both groups faced up to the task of learning how to live together in harmony. The Americans, brash by nature and background, came to respect Saudi customs, and the Saudis learned that industry, to be effective, depends on organisation and scheduling.

One possible source of conflict that emerged almost as soon as Casoc began to recruit, employ and train Arabs for work in the oil industry, was a radically different attitude toward work, money and other western concepts. Effective training of this new work force was an essential part of the operation from the start; indeed, under the terms of the original agreement, one of the fundamental Casoc objectives was the emloyment and training of Saudis. But the reaction of the Saudi people to this modification of their lives was not always enthusiastic; sometimes, in fact, the reaction was dark suspicion – as one story from Saleh Sowayigh, one of the company’s top Saudi employees at the time, suggests.

There were other, deeper differences, too. Some years later, as an example, Bill Palmer was entertaining Abdullah Sulaiman, the minister of finance and second most powerful man in the government. At sundown, the minister moved to a spot near the outer door, faced Makkah (Mecca) and performed his evening prayers, kneeling and prostrating himself according to Muslim custom. The minister showed no hesitancy and afterwards returned without comment to conversation with his hosts.

|

|

Schuler B “Krug” Henry and JW “Soak” |

Tom Barger, later to become company chairman, also had stories to tell about the Arab education of Americans on the subject or Arab culture. One involved a Bedouin who asked Tom to lend him 1,000 riyals, the equivalent of $300 to $400. Tom commented that this was a lot of money for a man who earned about two riyals daily. The Bedouin explained that he owed this large debt, and if he did not pay, he was in danger of being jailed as a debtor.

Then how, Tom asked curiously, did he expect to pay back the loan? The Bedouin replied that he had sent a relative to locate their segment of their tribe, and that when the relative found them the money would be brought back to Dhahran and paid to Tom.

How would the relative find their tribal members?

Oh, that was no problem. They were out there somewhere between Dhahran and the Dahna sands a distance of about 100 miles (160 kilometres).

But what assurance did the Bedouin have that the desert group would send the money back with the relative?

Of course they would send the money, the Bedouin replied. This was his family...

With the coming of the Americans in force, Al Hasa, at least near Dhahran, began to change visibly. More buildings were constructed – residences for families, improved bunkhouses for single men, shops and storehouses – and on a huge sandspit named Ras Tanura, some 25 air miles (40 kilometres) to the north and about 40 miles (64 kilometres) by road, construction of a huge oil port got underway. Close to deep water, a condition rarely found in the predominantly shallow waters along the Gulf’s western shore, Ras Tanura was to become an enormous oil shipping facility with 3,000 feet of trellis (914 metres) extending out to deep water and a 10-inch (25-centimetre) pipeline carrying oil from the Dammam field to Ras Tanura. A smaller shipping point was established at Al Khobar, where shallow draft barges could receive oil to carry to the Bahrain refinery about 16 miles to the southeast (27 kilometres).

Simultaneously, Casoc began to tackle special projects for, or in conjunction with, the government – a procedure that would become standard as time went on. A hydrographic survey of coastal waters, for example, was expanded to extend from Kuwait on the north to the Qatar Peninsula on the southeast; a survey team developed data that helped settle the location of the northern boundary with Iraq; and a geological group made astronomical observations in the Salwa area near the Qatar boundary.

|

|

The entire contingent of American |

There was more to the Saudi Arabia experience than just work, of course, though to most newcomers from the States, this was not immediately obvious. To them, the desert of Saudi Arabia was a place of uncertainty, a place that presented, even threatened, entirely new experiences. The vastness of the open unending land produced a touch of awe, even fear. How, the stranger might ask himself, could he find stimulus in its implacable dullness? Would it become a boundless prison, an unending monotony?

To some the answer was ‘yes’. But to others the desert was a challenge and a delight. In time, if the neophyte were to become a part of the working body, he or she would begin to see something in the great sweeps of rocky soil, in the majestic flow of the dunes, in the marvel of the night when the stars floated just beyond reach, and the moon turned the Gulf into a plate of burnished silver. In that awareness, the stranger began to abandon the fear of barrenness and to think more of the opportunity to move with so few limitations, to become a part of the space.

Max Steineke was that sort. The much loved chief geologist, who had investigated most of the surface of eastern Saudi Arabia, was an addict of dune travel. He enjoyed driving his car down the south slopes just for the hell of it, knowing that a successful journey depended on reaching the dune crest at just the right speed. If the car arrived at that critical spot too slowly, it would be stuck when the front wheels moved beyond the crest into space and the car body dropped into the loose sand. But if the vehicle came to the crest too rapidly, it would shoot out too far before it began to drop, hit the slope too hard and fast, and run into the hard ground at the base of the dune.

The pleasure of dune travel was greatest in the winter, after the rains had firmed the sand. On a journey beyond the area of normal field operations, caravans of two or three cars might travel together. With firm sand beneath the tyres and the smooth curves of the dunes ahead, the journey could assume some of the excitement of a glorified fox hunt.

Like a hunter behind hounds spurring his horse over the countryside, the driver of each car met the challenge of the dunes alone, but in close cooperation with his companions. Quickly, he selected his route as the view opened before him, maintaining general contact with the other cars travelling more or less abreast of him. A three-car caravan could move comfortably at a 30-mile-an-hour (48-kilometre) rate as each member swept down slopes, swerving quickly to avoid a sharp drop or a patch of scrub, engine roaring as the driver charged the next slope with only the sky and the crest in view.

In the open undulating country lacking roads and permanent human habitations, the rules of care for one another were well recognised. A car was not permitted to disappear for long. Where vehicles travelled in line, the one ahead was responsible for the one behind it. If that vehicle failed to appear after a reasonable interval, the one in front retraced its tracks until the missing car was found.

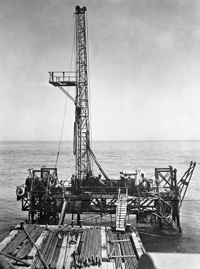

As Casoc settled down in Al Hasa, its active development programme of drilling and geological exploration was initiated. An oil reservoir had been located, but new channels were needed – channels reaching down nearly a mile below the earth’s surface to bring the oil flowing to the surface into tanks and then to the refinery on Bahrain.

Expansion of geological knowledge also continued at a brisk pace. In addition to surface studies, seismograph crews began to examine the position or the earth’s deep-seated rock layers, and in areas where the possibilities for oil accumulation appeared promising, structure drilling crews punched holes several hundred feet deep, not to find oil, but to determine the structure of shallow layers – structures that could be expected to continue to lower beds where oil might be found.

Almost at once, their exploration brought promises of rewards. Southwest of Dhahran, beyond Hofuf, evidence of a great uplift in the subterranean rocks began to appear and at Abu Hadriya, over 100 miles (160 kilometres) to the northwest, they began to drill a test well – a procedure that by then was almost a routine.

|

|

Early pipelines in the desert |

In Abu Hadriya’s open desert, far removed from human habitation, the drilling crews assembled their engines and pumps and reared a thin derrick in defiance of the limitless space that engulfed them. As in all Casoc wildcat operations, they established a small camp, including palm-thatched dwellings – called barastis – a bunkhouse, a kitchen, and a dining room. In one end of that building, they placed some battered easy chairs and a few well-worn magazines and books. When off duty, they hunted for gazelles or game birds to add to the diet.

When they arrived at Abu Hadriya in October, 1938, the weather was excellent, but during the following 17 months, they would experience all variations of climate: winter cold, spring winds and summer’s scorching heat. But with air cooling – when the generators and compressors worked – they survived comfortably and in December started to drill. For the following year and a quarter, they would dig and test, know discouragement and hope, would test and find nothing, then deepen and test again.

One of the highlights of that period was the April 1939 visit of King Ibn Sa’ud – as we then habitually called him – to the Eastern Province. He came, with his scores of retainers and his presence brought a gathering of the Bedouin shaikhs of the area, each with his retainers, to pay their respects, and on the plain below the Jabal Dhahran, the tents (chiefly white for this occasion) sprouted like mushrooms. The business of developing oil had to be shelved for the better part of two weeks while the facilities of the community were devoted to providing for the needs of the Saudi assemblage.

During the celebration, the king was taken to the newly developed port of Ras Tanura where he opened a valve on an oil line that started the oil flowing from the terminal tanks into the hold of the DG Scofield, the first tanker to be loaded with Saudi Arabian oil. The trickle that in later years would become a flood, had started.

Three months later, disaster struck. Dammam Well No 12 exploded in flames. At the time of the explosion, driller Bill Eisler and his Saudi helper were standing on the ‘stabbing board,’ a plank placed above the well connections. Below the derrick floor, in the cellar of the well, a Saudi crewman waited to open a small bypass pipe that would permit pressure from the oil and gas in the well to enter the chamber above the master valve. Suddenly, as the order was given for the Saudi in the cellar to open the valve on the bypass pipe, the world exploded: flames shot upwards, Bill Eisler jumped and, terribly burned, started to crawl to safety.

Saudi crewmen, rushing to help, were able to pull Bill’s burned body clear and to lift him onto a pick-up. But it was too late. Bill, like the crewmen on the derrick floor and in the cellar, died, and within minutes the heat of the fire melted the steel derrick legs, causing the structure to collapse.

For the men of Casoc, the fire was a disaster. With a tremendous fire, a wild well pouring out thousands of barrels of oil to feed the flames and no controls on the well, the entire Dammam oil reservoir was threatened. To make things worse, Casoc’s resident manager Floyd Ohliger was in Europe, headed for home leave in the US, and Charlie Potter, the drilling superintendent, was in America.

Casoc, however, immediately began to respond. Harry Rector, acting drilling superintendent, cabled San Francisco, caught Ohliger in Rome, asked for advice from the British oilmen in Iran at the head of the Gulf, and called for direct assistance from the refinery of Bapco (Bahrain Petroleum Company) which had equipment for fighting refinery fires. Simultaneously, men such as Bill Eltiste, the service superintendent; John Box, machine shop foreman; Cal Ross, labour foreman; John Ames, drilling foreman, and Ed Braun, plumber, set up an emergency station, a shelter and a kitchen.

They also laid another line from one of the early wells that had produced only water; now the well had value. They also lined up portable steam boilers from other drilling rigs near the burning well and fed steam into the fire in hopes of driving back the flames and seeing what connections had failed.

|

|

Burchfiel and Kerr operating the Fairchild |

In spite of the steam, flames continued to engulf the connections at the top of the well, so John Box’s machinists built a shield of sheet metal and gave it wheels. Encased in asbestos suits, partially protected by the shield, and with other men pouring water from a fire hose upon them, Herb Fritz and Walt Sims fought their way to the extension rods attached to the control valves. They found one rod bent and useless.

They managed to turn the other about two revolutions before it stuck and they were driven back by the heat. Next day, four men armed with a long wrench continued the effort and managed to close the valve partially before the rod broke and they were dragged back from the mixture of steam and fire. But their effort had paid off.

From San Francisco, meanwhile, Socal, which had been sending advice by radio and fire-fighting equipment by plane, sent word that Charlie Potter, the drilling superintendent on home leave, and Myron Kinley, famous battler of oil well fires, together with a team of fire-fighting specialists, were flying to New York en route to Saudi Arabia to stop the flow of oil and gas and the resulting fire.

The men of Casoc were not overjoyed. By now, the massive torch had become the personal adversary of the Casoc field organisation. Coming from every department, men had given their contributions, facing searing heat, the loss of hearing – because of the shrieking jets – and, even the threat of death.

Were outsiders now to come in and apply the coup de grace? Ed Braun is reported to have stated the field attitude when he grunted,’ Nuts! This is our fire.’

Both San Francisco and the field force recognised that one way of ending the fire would be to somehow drill a hole in the casing, or one of its remaining effective connections, and then pump drilling mud down-under enough pressure to stop the oil from flowing upwards into the flame.

To achieve this, San Francisco favoured a tunneling operation, exposing the casing well below the surface, but the men at the well could see a pipe connected to the casing and rising from the cellar of the well.

They concluded that this was the better location for the tap, so again John Box went into action, building a tap to fit the raising pipe, and again the firefighters braved the heat of the fire to attach what they call ‘a hot tap.’ Under the protection of water spray, they slowly placed nuts and tightened them on each bolt, crawling away when the heat threatened to overcome them.

They struggled for two days before the tap was firmly placed, but on July 18, 10 days after No 12 had erupted, they cut into the casing and started pumping mud down to kill the flow from the reservoir, and a few hours later the fire flickered and died. The watching men, shouting and pounding each other, knew they had won.

In September, 1939, Europe exploded in war. America was not involved, and though fewer ships were available to bring men and supplies, and communications became more difficult, generally, the Saudi Arabian development continued without faltering.

By early 1940, the Casoc field organisation had grown to 435 Americans and 3,300 non-Americans, chiefly Saudis. Of the Americans, 45 were wives, and 16 were children. As more families arrived, additional housing was built. By then too, Saudis were moving to positions of responsibility. They were head men on drilling rigs, lead men and sub-foremen on construction, clerks in offices.

Out at the Abu Hadriya rig, meanwhile, drilling had continued – though San Francisco was again getting discouraged; the drilling bit was down below 10,000 feet (3,048 metres), more than twice the depth of the Dammam wells, but had found no oil. Hadn’t the time come to write this one off as a bad investment?

|

|

Schuyler B “Krug” Henry and Robert P |

In the field, Bill Scribner, the foreman, said no and, the story goes, pleaded for a few more days. Within that time, a core (a sample) of the formation was brought to the surface and turned out to be limestone saturated with oil. Bill shouted so loudly as he reported the event to Dhahran headquarters, that those receiving the message contended that Bill could have delivered his good news across the more than 100 miles (160 kilometres) of desert without radio assistance.

About the same time, in the area beyond Hofuf, chief geologist Max Steineke, after one of his roller coaster journeys through the rounded hills of drifted sand, developed the belief that he was passing over a geologic high, that is an area where the earth’s rock layers had been raised above those around them. Just how he developed this suspicion is not clear, but his hunch must have been strengthened when he discovered a patch of rocks older than those of the surrounding surface.

In any case, on his recommendation, the company moved into the area with structure drills. Their shallow holes confirmed Max’s suspicions that there was a structure, or arch, in these rocks, and confirmed again Max’s reputation as a geologist of unusual ability. Indeed, his recommendation on this was an important part of the Saudi Arabian achievements that later brought him an award for having discovered more oil than anyone else in the history of the industry.

On October 19, 1940, as the drills gnawed their way through the Abqaiq rock toward what would be another important discovery, Bill Palmer and Bill Burleigh, being of nocturnal persuasion, had retired to the upper floor of the Dhahran clubhouse after most members of the community had gone to bed. This was a night for contemplation and the pursuit of peace.

Then, in the stillness, they heard the hum and rumble of motors. A plane was flying somewhere near – in the dark. This was unusual. Why would a plane be over Dhahran at night? Without warning, the quiet was shattered as the roar of explosions burst from the side of the jabal and the two Bills, startled and bewildered, were racing downstairs, where half-clad people were pouring into the streets – attractive targets if strafing were to be part of the plane’s attack.

After circling a few more times, the plane departed. Examination by the light of morning disclosed that the total direct damage from the bombing was confined to punctures in two small pipelines. The inhabitants of Dhahran also learned during the following day that three other planes had dropped small bombs on the Bahrain refinery with similar lack of damage. They also learned that the planes were Italian: Benito Mussolini broadcast a public apology to Ibn Sa’ud, explaining that the visit to Dhahran was a mistake, as the intended objective had been the Bahrain refinery in British-controlled territory, a plant that was the source of petroleum products for the British war effort in Europe.

In the late spring of that same year the war came closer still. In Iraq, just to the – north, the Iraqi army besieged the British “ airbase at Habaniyah. The siege was broken only after a British relief force arrived.

|

|

The first well at Al Alat, 20 miles (32 km) |

Recognising such growing threats to peaceful operations, Casoc owners decided that Saudi Arabian activity should be reduced to the minimum required by the concession agreement and so the evacuation began – the last group of wives departing for home in May, 1941. What we would call ‘the time of the Hundred Men’ had begun.

It was not too soon. On December 7, only seven months later, Japan struck at Pearl Harbor and overnight this small outpost of an American industrial organisation, joined to the San Francisco parent by steamship and plane, was immediately cut off. Thereafter, food, tools, other supplies might trickle in – or might not.

This wasn’t apparent in Dhahran at – once. Manpower had already been reduced to near minimum and though shortages existed, they were not serious. The initial reaction to Pearl Harbor was surprise and outrage, but not panic, and if exploration and production faced limitations, there were other things to keep the’ hundred’ busy.

The holding period in Saudi Arabia provided the Casoc manager and his advisers with the rare opportunity to analyse programmes for public betterment some of which had been inaugurated in previous years – and to make plans to expand those that had shown favourable results. During this period, the Americans came into even closer contact with their Saudi hosts – as their anecdotal history suggests. Les Snyder, later to be an Aramco vice-president, never forgot the ability and determination shown by one young Saudi who had been trained by the company in the operation and repair of tractors.

One day, driving one of Casoc’ s battered cat tractors, with steel treads poorly suited to desert travel, the young man discovered that the machine had developed a leak in the fuel line, 100 miles from Dhahran (160 kilometres).

His repair equipment included some rags, his lunch and his ingenuity. From his lunch, he obtained some dates and made a poultice of mashed dates which he applied to the leaking fuel line, and tied in place with a bandage of rags. The bandage failed frequently, but the young man continued to replace and adjust it and after four days of struggle, he brought the reluctant tractor into camp. Another Snyder anecdote shows the basic honesty that was standard in those early, simple days. Charged with getting hold of a consignment of 350,000 riyals in cash (close to $100,000) for company use, Snyder went to Riyadh.

His guide, who had been instructed to conduct him to a certain money changer, brought him on foot through the crowds and confusion of the streets to a man named K’aki. Les had never heard of K’aki until he received a chit, a small piece of paper, addressed to this man. But in a small shop several Saudis examined the chit that Les presented, finally appeared satisfied, opened a door to an adjoining small mud walled building to reveal piles of gunny-sacks filled with coins.

Les was confounded. What should he do? How could he keep track of 20 men, amid teeming crowds, each going his own way? What was to prevent any one of them from disappearing down a side street with his sack of coins? But, faced with no reasonable alternative, Les resigned himself to trust and returned to the truck where the sacks were being dumped into the truck bed.

|

|

Tom Kock and a young Saudi companion |

By 1942, Saudi Arabia was feeling the impact of the war. Shipments of rice, a staple of Saudi diet, no longer were received from Burma, because of the Japanese invasion, and prices were rising alarmingly. In response, the king was urging Casoc to employ more Saudis, thus distributing more money to the people.

From that request – plus a shortage of parts and tyres for Casoc’s sedans – came the famous episode of the ‘ camel haul,’ by which Casoc supplied one of its drilling operations. Who had the brainstorm isn’t clear, but again Bill Eltiste probably contributed.

Certainly he was involved – as was Khamis ibn Rimthan, the Saudi who performed so effectively as guide for the geologists over the years. Although he was a government employee, Khamis seemed available whenever the company needed him.

This time Khamis was asked to accept a contract to haul supplies by camel for about 30 miles (48 kilometres), from the company storage yards at Dhahran to the drilling site at Abqaiq No 3.

He would be paid an amount approximately equal to the cost of transporting the same material by truck. Management suggested that he go up country and recruit owners of camels, asking them to bring their animals to Dhahran to haul supplies to Abqaiq. He would decide what he would pay the owners from the money that he would receive from Casoc.

Khamis agreed, provided that he could obtain the needed recruits, but after about a week of travel through that portion of desert where the tribes were enduring the summer, he returned discouraged.

The more affluent Beduoins, with the stronger camels, didn‘t need the money and those with lesser possessions and poorer camels concluded that their stock couldn’t stand the 30- to 70-mile (48- to 112-kilometre) journey in the heat.

Casoc’s management persisted. If the Bedouins would not come for what Khamis had offered them from the contract money, would they come for the full contract sum -with Khamis receiving full salary in addition from the company? Again Khamis agreed to try.

After this second effort, he returned with promises for 75 to 100 animals. Cal Ross, the company’s representative, was assigned to work with Khamis to arrange supply dumps and other facilities, and the accounting department was asked to devise procedures for paying the Bedouins. Cal planned to transport sufficient supplies to meet the needs of the drilling operation for a month or two, and calculated that this would provide possibly two weeks’ employment for the anticipated 75 or 100 camel-drivers.

On the day before the first haul was to start, the camels began to collect in the open area beyond the storage yard. Soon the expected 100 were there – but the camels kept coming. They kept coming, in fact, for two full days until about 500 darkened the rocky plain, thereby providing Cal and Khamis with a crisis. They had expected to provide work for a week or so to 100 camels and their drivers and now they must share that employment among five times that number. In fact, they had to make hurried additions to their supply dumps to provide all animals with one load.

And so the first morning of loading progressed. Each driver was given a chit for each sack or drum that his camel carried. At Abqaiq, the tool house foreman would sign the chits when the loads were delivered. When the driver returned to Dhahran and presented his chits at the booth set up by the accounting department, he was paid for his labours.

|

|

Exploration party using a plane table near |

As the day progressed, the open desert near Abqaiq became dotted with small clusters of camels and drivers. They would move slowly for a few miles in the midday heat, then the loads and saddles would be removed from the animals, permitting them to seek such skimpy wisps of dried grass as might remain between the rocks.

The farm came first. In a suspiciously green patch of ground on what used to be the Al Khobar road, Furman plowed, seeded and planted and irrigated – and came up with crop after crop of carrots, onions, tomatoes, lima beans, cucumbers and even sweet corn. Then he started a ranch – stocking it with rabbits, pigeons, sheep, goats, and camels – built an incubator and began to enlarge and improve the breeding of all those animals. By the end of the war Furman’s Ranch counted 6,000 chickens, 2,000 pigeons, 500 rabbits, 500 sheep and, a highlight, 1,200 cattle – the result of a startling proposal put forward by an ancient Saudi named Mutlag. He proposed to journey into Yemen, where cattle were raised in watered lands beside the Red Sea, and collect cattle and drive them overland to Dhahran if Steve Furman would promise to buy them when they arrived.

Steve, noting that between Yemen and Dhahran lay over 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometres) of mountains and deserts, wasn’t sure whether Mutlag was crazy or not, but concluded that this ancient desert traveller might possibly be able to make the drive; moreover, if he failed, what had Steve to lose? He promised to buy on delivery.

There followed what Wallace Stegner in his book, Discovery, describes as a drive that rivalled the great exploits of the American cattlemen who pushed their herds from Texas to the Kansas railhead in the years of our western expansion. Those men of the west had money, experienced cowboys, trained cow ponies and, above all, a welcoming land in which to travel: plains covered with grass on which the herds could graze as they moved. Mutlag had his young son, his aging legs and a harsh land on which no cow could survive for long except in the oases scattered along the route.

In Yemen, where he had friends, Mutlag collected his cattle and in January, 1942, started his drive. He worked his animals along the edge of the Tuwaiq mountains, then left the high country to reach Al Kharj, then crossed the desert to the great oasis of Hofuf. He was months en route, as he was forced to rest his herd after it reached each oasis, permitting the animals to eat and renew their strength.

|

|

The Fairchild’s crew in 1935 ... RC “Dick” |

The last leg of the journey must have been the most difficult of all. From Hofuf to Dhahran little grass grew, even in the times of the winter rains. Presumably, Mutlag counted on those meager blades and the ability of the herd to exist with little water while it traversed the last 150 to 200 miles (241 to 321 kilometres).

But in spite of the hazards, Mutlag did deliver, though possibly 75 to 100 out of a starting herd of about 150 actually reached Dhahran. Miles Lupien contends that the cattle were so thin they had to be given muddy water to drink to permit them to become visible. But to Furman they were the beginnings of a herd. And Mutlag must have found the venture profitable, for he repeated the drive during the following winter when the need for his replacement stock was of growing importance. He skipped the winter of 1943-1944, then tried again in 1944-1945. But that was a terribly dry year and most of Mutlag’s cattle died before reaching Dhahran.

In retrospect, the holding period – the time of the Hundred Men – seems a long as well as a romantic period. Actually, I know, it was quite short. By early 1944, in fact, it was over. Casoc, for instance, became the Arabian American Oil Company – Aramco – and instead of organising camel hauls and cattle drives, we began to plan programmes of expansion. Soon new arrivals, strangers to the Saudi Arabian experience and the philosophies it had created, began to appear – the first trickle in the flood that would engulf us in the coming months.

Above all, the Hundred Men held on. They maintained the petroleum operation and despite the handicaps of war helped lay the groundwork for the extraordinary achievements of the post-war period. Their story is not the performances of heroes or supermen; they were not. They were simply a small group who shared a common objective and possessed the perseverance and ingenuity to achieve it. In this spirit, it is a bright chapter in the story of one American corporation that combined humanitarian and industrial objectives, and found them to be compatible.