A Saudi employee tightens well head of Dammam No 15

A Saudi employee tightens well head of Dammam No 15

THE oil-bearing rock was in a layer that geologists had dubbed the Arab Zone. The well, drilled into the geological formation they called the Dammam Dome, capped a quest that had lasted nearly five years.

It made possible the commercial development of oil in Saudi Arabia, and all that flowed from that: Prosperity for the kingdom’s people, resources with which to build the country’s future, and strength to make its moderating voice heard in international affairs. The find also set Aramco firmly on course toward becoming the world’s largest oil-producing company.

The discovery well’s name, determined months before, could not have been more prosaic: Dammam No 7. Yet, of all the thousands of wells drilled in Saudi Arabia since, “Lucky No 7,” as it came to be called, is the mascot, the symbol of first success, writes Mary Norton, a veteran contributor to Aramco World, who has lived in Saudi Arabia since 1958.

Dammam No 7 stands on a hill named Jabal Dhahran – the surface expression of the Dammam Dome – near a cluster of peaks called Umm Al Rus. Today, Aramco’s gleaming high-tech Exploration and Petroleum Engineering Centre (Expec) lies just up the road, and the company’s headquarters community of Dhahran just beyond. The town, green and comfortable, is far different from the drilling camp it once was, and the silicone-chip and stainless-steel technology of Expec is light-years beyond that of the 1930’s; nonetheless, Aramco has never lost sight of its geological roots.

|

Pilot refinery at terminal area, office and |

Those roots date back to May 1933, when the original oil concession agreement was signed. The search for oil began the following fall, on September 23, when American geologists Bert Miller and Krug Henry crossed to the Saudi mainland from Bahrain. They landed at the sleepy coastal village of Jubail, about 105 kilometres (65 miles) north of the Dammam Dome, and that same day journeyed by car and camel to look over Jabal Berri, some 11 kilometres (seven miles) to the south.

What they experienced on their return was only a mirage but seems, in hindsight, to have been something more. They looked across a great salt flat and suddenly, as Wallace Stegner tells the story in Discovery!, “the solid earth veered before their eyes, the intense light flawed and changed, and unknown Arabia grinned at them – a sudden distorted grin – as the ring of the horizon boiled and floated ....The pearling town of Jubail, which they knew had only a thousand or so people, threw up a skyline like New York’s, a vision of cloud-capped towers and ... palaces.”

The mirage proved to be less a desert delusion than an uncanny look into the future. Jubail today is a sprawling industrial city whose towers, stacks and minarets form a striking skyline against the coastal plain and whose factories and refineries are fed and fueled with hydrocarbons produced by Aramco. And elsewhere in the Kingdom – in Makkah and Medina, Riyadh, Jeddah, Yanbu’, Abha, Taif, Hofuf, Dammam and in countless other cities and towns – developments have taken place on a scale of such magnitude and in so compressed a timespan that even those who have witnessed them are often incredulous.

The wellspring of these achievements was Dammam No 7: Testing the discovery, it flowed 1,585 barrels a day on March 4, 3,690 barrels on March 7, 2,130 nine days later, 3,732 five days after that, 3,810 the next day, and so on until the head office cabled that they saw no reason to continue the test. Dammam No 2 and Dammam No 4 were also deepened to the Arab Zone and they too proved good producers. Jubilation reverberated from Dammam Camp to Riyadh and San Francisco, where Casoc, the California Arabian Standard Oil Company formed for the Arabian venture, joined in celebrating the victory.

Saudi Arabia’s King ‘Abd Al’Aziz Al Sa’ud, hopeful but not sanguine, had given all possible cooperation to the venture, and not long after October 1938, when the presence of oil in commercial quantities was officially declared, plans began to unfold for his visit to Al Hasa, as the Eastern Province was then known.

In the spring of 1939, the king and his retinue moved east from Riyadh in a caravan of 2,000 people in 500 cars, across the red sands of the Dahna and along desert tracks to a place near the oil camp, officially named Dhahran only 10 weeks before. In an atmosphere of conviviality, the visitors set up a city of 350 white tents within view of the camp for festivities which included inspections, banquets, receptions and boat rides in the Gulf.

The timing of the visit coincided with the completion of a 69-kilometre (43-mile) pipeline from the Dammam oil field to the port of Ras Tanura, where the tanker DG Scofield lay waiting. On the last day of celebrations, Stegner recounts, King ‘Abd Al ‘Aziz Al Sa’ud unhesitatingly “reached out the enormous hand with which he had created and held together his kingdom in the first place, and turned the valve on the line through which the wealth, power and responsibilities of the industrial 20th century would flow into Saudi Arabia. It was May 1, 1939. No representative of the US was present, even as an observer. The US had not yet accredited any representative to Saudi Arabia.”

What people knew at the time was truly cause for celebration: Oil had been found and was being produced. What they did not know was that the Dammam Field would become but one bead in a whole necklace of discoveries by Aramco – 52 oil fields in all, including Ghawar, the world’s largest onshore field, and Safaniya, the world’s largest offshore field.

|

Ready to start bit into well hole |

Spreading out to explore distant corners of the million-square-kilometre (385,000-square-mile) concession area, the pioneering geologists could not have imagined that one-fourth of all the world’s oil lay beneath their feet. Nor could they have envisioned that the kingdom’s recoverable oil reserves would one day run to 167 billion barrels – more by far than in any other nation on earth – or that recoverable natural gas reserves would surpass 135 trillion cubic feet. To them, any oil at all amounted almost to a windfall, and gas was just a nuisance.

Neither could the first Saudi and American drillers have imagined, even after they struck oil, that Dammam No 7 would be capable of producing not for months or years but for several decades into the future, or that this one well would pour out more than 32 million barrels of oil. And the planners and engineers of the company’s early days surely did not dream that Aramco’s daily crude-oil production would ever approach 10 million barrels a day, as it did in 1982, or that cumulative production would exceed 53 billion barrels of crude oil and 1.6 billion barrels of natural gas liquids, as it did last year.

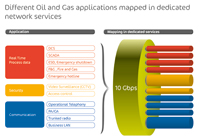

Indeed, little about Aramco today was within the conception of the company’s pioneers. Aramco now has 43,000 employees, about 550 wells in production, 20,500 kilometres (12,733 miles) of flow-lines and pipelines and more than 60 gas-oil separator plants. Gas is no longer a dangerous nuisance, but an important product: There is an extensive gas-gathering system whose three main processing plants can handle four to five billion cubic feet per day of raw natural gas, and the company operates two large fractionation plants for natural gas liquids – as well as three oil terminals, two liquefied petroleum gas terminals and a good-sized refinery.

Nonetheless, back in 1938, there were hopes and hints that something great might come to pass. Even before the concession agreement between Saudi Arabia and Standard Oil of California was signed on May 29, 1933, geologist Fred Davies, who worked for Socal on Bahrain, looked across the Gulf at the limestone silhouette of Jabal Dhahran and noted its resemblance to Jabal Dukhan in Bahrain, where oil had been discovered in 1932.

It was not surprising, then, that Bert Miller and Krug Henry should examine those rugged hills within a week of their arrival at Jubail. “We got on one of the beds and drove around it,” Miller would later relate, “and we knew then, in just a few minutes, it was like a copy of Bahrain Island.” After surface mapping and aerial reconnaissance, and though exploration parties were working intensively in other locations, the Dammam Dome remained the best bet, and Miller recommended that the search for oil should begin there. The hope was that they would find oil at the same depths as on Bahrain – in the 600-metre (2,000-foot) range known as the “Bahrain Zone.”

The wildcatters – drillers, rigbuilders, and construction men who came over from Bahrain in the fall of 1934 – were men like the geologists in their light-hearted affection for challenge, their stamina, and their undaunted – and well-founded – belief in their own abilities. Every one of them, Stegner wrote, had “been knocking about the world for years.”

Still, the Dammam Dome tested them. An early edition of the Aramco Handbook states that “not only the drilling rig and equipment, but every item of lumber, hardware, plumbing and steel needed to create and supply living quarters, pipe for water, transportation equipment and spare parts, food and personal requirements had to be brought over in a supply line reaching from the US.” In addition, water wells had to be drilled, roads built and power provided where none of these things existed.

With the help of Saudi recruits, for whom drilling – and indeed the very notion of scheduled shift work – was entirely new, Dammam No 1 was spudded in on April 30,1935, using an old cable-tool rig. The obelisk-shaped derrick, the area’s tallest structure, looked out over desolate terrain that was hardly softened by distant black Bedouin tents. After seven months of sputtering between hope and disappointment, the well produced a strong flow of gas and shows of oil just short of 700 metres down (2,300 feet) – but an equipment breakdown forced the crew to kill the well and later plug it with cement.

The drillers rigged up Dammam No 2 the same day. No 2 was almost too good to be true. Spudding in on February 8, 1936, the crew had drilled to a depth of 663 metres (2,175 feet) by May 11. This was the targeted Bahrain Zone, and from it came a flow of 335 barrels of oil a day when the well was tested in June. A week later, after acid treatment, it flowed at the equivalent of 3,840 barrels a day, just like that.

The news was what Casoc had wanted – and needed – to hear. Back from San Francisco came instructions to put down Dammam Nos. 3, 4, 5 and 6. Contrary to the cautious industry practice of awaiting proof of field size and commercial viability before establishing a permanent camp, Casoc cabled Davies in June to expect a shipment of air-conditioned family cottages, as well as several bachelor housing units. And for good measure, word came in July to prepare Dammam No 7 as a deep-test well.

More work meant more men and more material, and soon there was more of all three than the camp could handle. By the end of 1936, the number of American employees in the field had risen from 26 to 62, and 1,076 Saudis had joined the strange new enterprise. About that time, however, things out by the drilling rigs started to turn sour.

|

King Abd Al Aziz confers with US President |

Dammam No 1, drilled to below 975 metres (3,200 feet), proved a loser. No 2 “went wet” and started producing eight or nine times more water than oil. Dammam No 3 had a flow of no more than 100 barrels of heavy oil a day, with 15 percent water. No 4 was dry as a bone. No 5 had no production either. A wildcat well at Al Alat, a prospect 20 miles northwest, was a bust all the way down to 1,380 metres (4,530 feet). Dammam No 6, drilled in early 1937, showed only a little oil mixed with water.

On December 7, 1936, the wildcatters had spudded in the deep-test well, No 7 The other wells had been disappointing, but when it came to trouble, Dammam No 7 proved to be in a class by itself.

There were delays and stoppages. Drill pipe stuck. Rotary chains broke. Bits were lost down the hole and had to be fished out, and walls caved in. As the steam-driven rotary rig ground toward the Bahrain Zone, the results remained the same: No oil. No oil.

Ten long months later, on October 16, 1937, at l,097metres (3,600 feet), the drillers saw the first sign: two gallons of oil in a flow of mud cut with belches of gas. Then, on the last day of the year, control equipment failed and the well blew out. After drilling 1,382 metres (4,534 feet) into their best prospect, the Casoc crews hadn’t found enough oil to fill the crankcases of their own trucks.

The optimism of 18 months before began to look foolish, and a somber mood descended on Socal’s management. Sides were chosen, fingers were pointed and hard questions were raised about the future of a venture that had cost millions and proved nothing.

Chief geologist Max Steineke, who knew more about Saudi Arabia’s geology than anyone, was called to San Francisco early in 1938. Since his arrival at Jubail in late 1934, the insatiably curious and energetic Steineke had ranged far and wide in the concession area and had recently crossed Arabia to Jeddah and back, hunting fossils, observing rocks and dips, synclines and anticlines. On his return, he wrote a seminal paper on Saudi Arabia’s geology.

Waiting to hear his opinion were men who had gone far out on a limb in the expectation that oil would by now be found. Some could already hear, in their minds’ ears, the wrath of their stockholders, and were more than ready to pull out of the Saudi Arabian venture altogether. But Steineke had never wavered in his belief that oil lay beneath Saudi Arabia’s stratigraphy, and now he stood his ground. Still unable to prove his hypothesis, he fell back on his formidable knowledge, intuition and optimism.

He was dramatically vindicated. In the first week of March, 1938, while Steineke was still arguing his case in San Francisco, Dammam No 7 found what it was looking for at a depth of 1,440 metres (4,727 feet) – less than 60 metres (200 feet) farther down. When Dammam Nos. 2 and 4 confirmed the find, Dammam Field was declared a commercial preducer.

What followed, in the 50 years since then, has been one of the classic national and corporate success stories. Saudi Arabia prospered, Aramco grew, and the Saudi-American partnership became a model of the fruitful transfer of technology and of cross-cultural cooperation. But the success was not automatic: It was earned, every day, over and over again in the following years, and much of it was attributable to the character of the men, Saudis and Americans, who dealt honestly and forthrightly with each other and with the novel and less dramatic difficulties of the post-pioneer period.

Despite their roving instincts, many of the first American employees in Saudi Arabia stayed on and grew with the company. Fred Davies and Tom Barger, a junior geologist who arrived in 1937, each became chairman of the board of Aramco. Floyd Ohliger, a young petroleum engineer who arrived in 1935, supervised the construction of the Al Khobar pier and later dealt with King ‘Abd al ‘Aziz on company matters, retired as a vice president in 1957 Max Steineke had “at least a finger” in the discovery of every oil field in Saudi Arabia until his death in 1952. And some of the wildcatters stayed, too, like Bill Eltiste. His Aramco-sponsored efforts to help interested local Saudis get started in business led to a new class of Saudi entrepreneurs and a vastly improved and diversified local economy in the Eastern Province.