Ghawar ... a prime candidate for ‘rest’

Ghawar ... a prime candidate for ‘rest’

WITH the giant offshore Manifa field pumping crude since April, Saudi Aramco is implementing a policy that appears rather puzzling. How is it that some 1.5 million barrels per day (mbpd) of new production will come on stream by 2017, yet total capacity will remain unchanged at 12 mbpd?

Officials explain that Aramco will “relax” older fields as the fresh capacity comes on. But this field management strategy to extend productivity will come at a price – in permanently lower output rates from key Saudi fields.

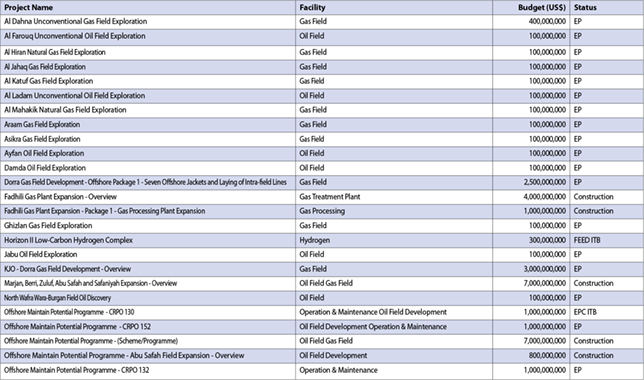

Saudi Arabia leans heavily on production from a handful of fields that were developed to maintain conservative plateau production rates for 20 years or more, officials explain. The state firm undertakes regular “maintain potential” drilling to keep output steady year-to-year while managing the water cut, which the company insists is still around 30 per cent, even at mature fields.

But some of the old workhorses that have been pumping at the same rates since the 1940s could now benefit from lower plateaus. Aramco sources say the company will reduce “maintain potential” drilling and ease down pumping rates to keep these aging fields producing for many decades to come. Their production will be replaced by 500,000 bpd from Manifa by July and 400,000 bpd more by end-2014, while Khurais will add 300,000 bpd by 2016 and Shaybah 250,000 bpd by 2017.

But if wells can be turned down, can’t they be ramped back up again? Not necessarily, says Aramco. Part of the explanation is that once production has been “relaxed” in this manner, it can no longer be counted on as sustainable capacity.

Indeed, as the delicate situation at the supergiant Ghawar field demonstrates, rapidly rebooting fields once their production has been reduced can cause irreparable harm, leading to a long-term loss of resources.

Aramco says that Ghawar, which has been pumping 5 mbpd for decades, is the prime candidate for rest. The northern Ain Dar/Shedgum fields have been producing 2 mbpd consistently since 1970, save for a brief fall to 1 mbpd in the mid-1980s.

The key to such performance is maintaining reservoir pressure, which has stayed around 3,000 PSI. If the field is adjusted to a lower plateau, as is being considered, it cannot quickly or safely be ramped back up to 2 mbpd, says one informed source.

A sudden surge in production could reduce pressure, separating associated gas out of the liquid. If that happens, large volumes of previously producible oil “will never come out of the ground,” the source says.

In any event, Aramco sees no need to tap the full capacity of its largest, oldest fields even if they could be easily restored to previous production rates. It has plenty of other fields that have produced less than 5 per cent of their oil-in-place, and mature ones with untapped reservoirs.

The latest long-term demand forecasts also suggest a lower-than-expected call on Saudi crude capacity. Aramco may have run out of idle giants – Manifa, Khurais and Khursaniyah were the last – but it has billions of barrels in undeveloped reservoirs at Berri, Zuluf and Safaniyah.

Its ambitious plans to recover some 70 per cent of oil-in-place means it develops fields to produce far below their full potential.

.jpg)