Pemex ... taking Aramco’s help

Pemex ... taking Aramco’s help

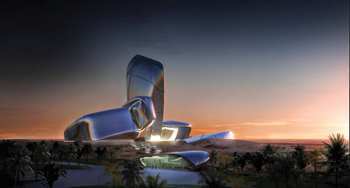

SAUDI Arabia and Mexico are working closely to push forward cooperation in the petroleum sector, says Mexican Ambassador Arturo Trejo.

He says closer mutual cooperation would help realise mutual interest, as “Mexico has recently opened up its oil sector to foreign investment and there is also big potential in the petrochemicals and associated sectors.”

Trejo, who spoke about the progressively growing relations between the kingdom and Mexico, underlined the importance of increasing investment in the oil sector to meet the growing demand for energy. To this end, he notes the growing presence of Mexican companies in Saudi Arabia. He points out a Mexican company has also won a contract for supplying industrial boilers to Saudi Aramco.

Mexico has extraordinary untapped natural resources. According to a report, the Latin American country has an estimated 545 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas and 13 billion barrels of shale oil. “Such projections indicate that any foreign partnership with Mexico can be mutually advantageous,” says the report.

Referring to cordial relations between the kingdom and Mexico, Trejo says: “We have an excellent political relationship and we closely cooperate on several multilateral issues with the kingdom.”

He says the Mexican foreign minister paid an official visit to Riyadh in March this year with a high level delegation precisely to “develop” this potential.

“We are now working closely ... and it is likely that we will have a presidential visit very soon,” added Trejo, while referring to the forthcoming visit of the Mexican president to the kingdom in the near future.

Mexico, the world’s tenth largest crude producer, is a significant player in the global energy map and the true potential is still to be tapped. The country has been a significant crude supplier to the US sending around 850,000 bpd last year, according to EIA.

Proven and probable reserves in the country amounts to 26 billion barrels of oil equivalent, and total reserves are estimated at 44.5 billion barrels. Yet, its output has been on decline over the last few years, dropping to 2.5 mbpd.

And while on the US side of the Gulf of Mexico, a lot of activities are on, Mexico feels, and rightly so, there is a scope to mimic that in its territorial waters in the Gulf too.

But Mexico apparently can’t do it alone. Falling output, the need to arrest nine straight years of output declines and to exploit the unconventional riches of the country, Mexico needed advanced technology, expertise and indeed the financial muscle.

The story begins some 76 years back, on March 18, 1938 to be exact, when under the stewardship of the then President (and General) Lázaro Cárdenas, the Mexican government nationalised the energy sector, declaring all mineral and oil reserves of the nation as belonging to its people, giving the government a monopoly in the exploration, production, refining, and distribution of oil and natural gas, and in the manufacture and sale of basic petrochemicals.

|

Birol ... Aramco has the ‘capability’ |

But the growing sectoral inefficiency forced President Enrique Peña Nieto government last December to reverse the policy, in place for more than seven decades, and open up the sector to global oil majors and private entrepreneurs. The world has indeed traversed a full circle!

The announcement has generated a big debate in the energy fraternity, both within and outside the country. Mexico today, as told by David Davila, the Head of Economic and Cooperation Sections at the Mexican Embassy in Riyadh, is reviewing various models – so as to ensure fair returns to the investors.

But they indeed cannot permit a rip-off. The treasure, the asset is dear to the national psyche and cannot be played around in a cavalier fashion.

The Norwegian model is indeed being looked at in Mexico City – rather closely. The reason is simple. The model permits reasonable profits to oil majors, yet at the same time, it does not allow any one taking the nation for a ride. For after all the asset belongs to the nation. Yet one thing remains crucial to success – transparency in all sectors.

Right now the state-run Mexican oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) is responsible for managing and exploiting the energy riches of Mexico. But the company seems to have hit a roadblock unable to reverse the downward slide. But the government also needs to tread a very cautious path.

For there are no dearth of nationalists clamoring against the move. Well-known artist Yoshua Okón argues that the “energy reform” currently underway will deprive citizens of income directed toward education, healthcare and anti-poverty programmes.

He underlines that Pemex is one of the most lucrative companies in the world. In 2012 it declared profits of over 900 billion pesos ($70 billion), comparable to those of American oil and gas giants like ExxonMobil and Chevron.

More importantly, Pemex has historically distributed its profits among the Mexican population more equitably than any other industry in the country.

Sixty per cent of Mexico’s spending on social welfare comes from oil income. Among the things this income currently pays for are education, health care and programs to fight extreme poverty. Every Mexican citizen owns Pemex, and the profits the company generates have made palpable differences in the lives of the Mexicans, he asserts.

Okón is hence of the view that President Enrique Peña Nieto push toward inviting oil majors into the sector will radically shift the distribution of oil profits from the public to a few private investors.

Hence before proceeding ahead and initiating the process, the government gave an opportunity to Pemex to advise the assets it would like to keep to itself. Pemex submitted its wish list last week. However, the list was not made public.

But as per reports trickling in, Pemex has asked to keep 83 per cent of its proven and probable (2P) oil reserves, and 31 per cent of its less-certain prospective resources.

The company is not seeking to maintain all of its Perdido Fold Belt deep-water development in the Gulf of Mexico, the major deep-water oil deposit straddling the US-Mexico maritime border, CEO Emilio Lozoya told Reuters.

Pemex also is not seeking to keep all of its large, geographically complicated onshore Chicontepec basin developments. Now it’s the turn of the ministry to decide which fields Pemex would keep and what would be on hammer. The ministry has until mid-September to decide – before moving ahead.

“We have to strike this balance between what Pemex keeps and what the nation keeps to tender to new participants,” Lourdes Melgar, deputy Mexican minister for hydrocarbons, told reporters. He anticipated “great interest” when Mexico launches its future bid rounds to auction off rights to Perdido blocks, given existing pipeline and other processing infrastructure in nearby US waters.

“We want a strong Pemex,” says Melgar, who along with the country’s energy minister, sits on Pemex’s board of directors. “A vision that aims to shrink Pemex would be very negative and is not an option.” Once Round Zero is complete, Mexico will launch an international bid round for oil and gas development rights each year through 2019, each one covering about 20,000 sq km, she says.

Three senior Mexican diplomats hinted the possibility of letting Saudi Aramco join the list of oil majors seeking a stake in the development of the Mexican energy sector.

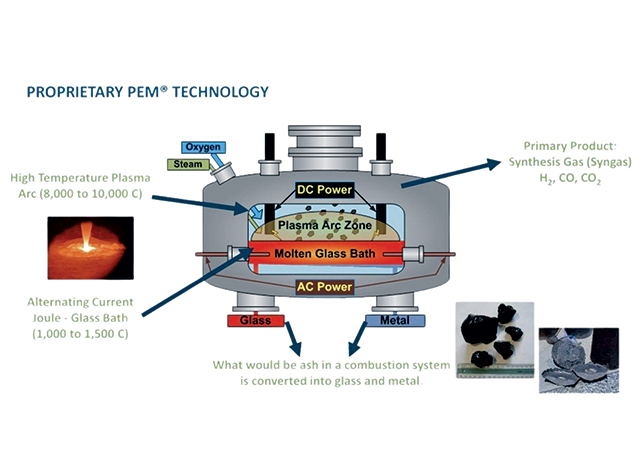

Although Aramco is a national oil company (NOC), yet Fatih Birol, chief economist and director of Global Energy Economics at the International Energy Agency in Paris, says that of all the NOCs, Aramco has the technology, the capability and the muscle to undertake critical technical pursuits to develop energy sector. And Mexico could be a test case.

-(3).jpg)