Sabic ... planning to invest heavily in OTC

Sabic ... planning to invest heavily in OTC

IN THE midst of the US shale gas boom that has raised hopes of an era of cheaper gas feedstock worldwide, Saudi Arabia is somewhat surprisingly pushing ahead with plans to build a petrochemicals plant that runs directly on crude.

Gas is not as abundant as it once was in the kingdom, but the decision by Saudi chemicals giant Sabic to pursue experimental technology goes deeper than that. Sabic is under pressure to show that it can innovate and create jobs for Saudis – and also to prove that it remains the leader of the Saudi petrochemical sector, where it is seeing a strong challenge from Saudi Aramco.

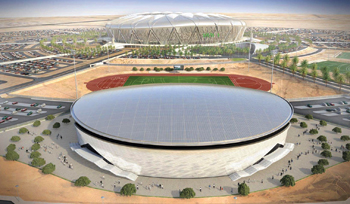

Sabic says its proposed oil-to-chemicals (OTC) project will convert 200,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude into chemicals – using technology, albeit untested, that yields the highest conversion. It would be far and away the world’s largest such plant, and is estimated to cost an eye-catching $30 billion, Saudi sources say.

By comparison, the $20 billion Aramco and Dow Sadara complex, set to be the largest single petrochemical project ever when completed in 2015, will run on 75,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day of naphtha and ethane.

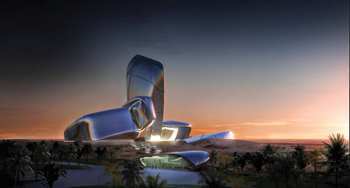

If approved, Sabic’s massive project, supported by the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, is slated for the western oil city of Yanbu by 2020. It is expected to produce new products and generate job opportunities.

The government, keen for Sabic to add value through innovation, is clearly pleased. “I have seen what can only be described as extremely impressive innovation that Sabic’s R&D efforts have succeeded in developing in petrochemicals,” Saudi Economy and Planning Minister Mohammed Al Jasser told a recent conference in Bahrain.

Attendees at the event were less convinced. They say the proposed plant is too big and depends on unproven technology, adding that Sabic has not run a test plant before rolling out a world-scale project. “It will be a big learning curve, as the chemistry is unpredictable. I would have started small,” said one industry source. Aramco is currently doing just this as it tests OTC technology at a demonstration unit in China to determine the future viability of a 80,000 bpd plant.

Others fail to see the logic behind using crude, arguing that for liquid feedstock it would make more sense to use proven technology to crack naphtha. Even naphtha crackers would struggle to compete with petrochemical units that run on gas, though: Producing ethylene from market-priced naphtha costs around $1,100 per tonne, compared to around $500/tonne using US shale gas, and less than $100/tonne using gas in Saudi Arabia. It will be expensive to produce petrochemicals from an OTC plant that uses market-priced crude, industry sources say.

That has led to suggestions that the petroleum ministry, which allocates feedstock, has given Sabic a special deal. Sabic has complained bitterly that it has for years received no new allocations of gas feedstock, which is priced at 75¢ per million Btu. Crude, however, is potentially available in spades, with Aramco producing some 2.5 mbpd below its production capacity. Tapping crude might also be relatively cheap if Riyadh can navigate World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, which ban the selling of oil internally at fixed prices below the international market rate. This means Sabic may not be eligible to pay the cut rate of $4.50 per barrel offered to Saudi power plants, say sources familiar with Saudi pricing policy. But a discount of some nature might be possible, particularly if the chemicals created don’t leave the country.

There is a precedent: Riyadh offers propane and butane to domestic industrial consumers at below market price. It says the lower cost of selling natural gas liquids (NGLs) domestically justifies the discounts. However, the government charges domestic petrochemical plants the European market price for naphtha, the closest competing chemical feedstock to crude.

Economics aside, Sabic’s new project is also about ensuring it is aligned with the government’s most pressing issue: jobs. There are 1.3 million Saudi students in universities inside the kingdom, and 800,000 more studying abroad on the government’s dime, said Jasser. And that’s not counting the millions of unemployed or under-employed Saudis.

Sabic has taken a lot of heat for using advantaged 75¢/MMBtu ethane to generate big profits, but not enough Saudi jobs. Conversely, in the last decade, state-owned Aramco has invested in some $40 billion of petrochemical plants, supported by integrated value parks, where it hopes to foster tens of thousands of Saudi employment opportunities. Aramco’s Competitive Saudi Energy Sector initiative aims for 500,000 direct and indirect jobs.

As a listed company partly owned by the government, Sabic cannot do social projects on Aramco’s scale but is trying to demonstrate it can do its part. Last year, it was able to fend off an Aramco-driven proposal to increase gas prices, arguing it would harm industrial producers, which are job creators and the backbone of the Saudi stock market – one of the few places where ordinary Saudis can get a slice of the country’s vast oil wealth. A key reason its OTC is getting rave reviews from Riyadh is that Sabic claims it will foster 100,000 jobs.

-(3).jpg)