Corporations and investors have been pouring money into renewable energy projects, seeing an opportunity to grasp the Holy Grail of socially conscious investing: do good while doing well.

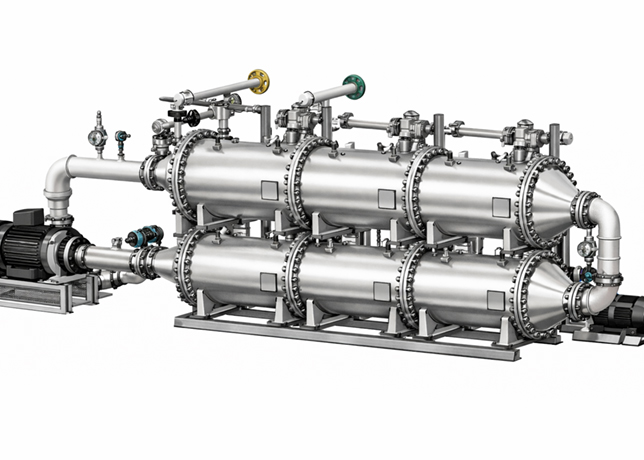

But sharply higher interest rates have further stressed a model strained by soaring prices for steel and silicon, vital for wind turbines and solar panels.

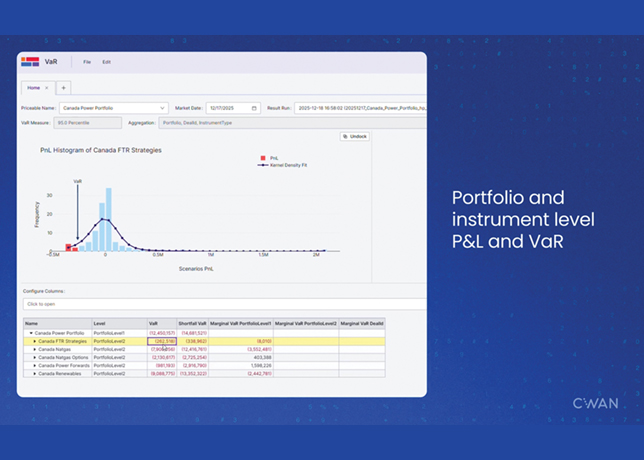

Higher costs have buyers and sellers of renewable power projects recalculating potential returns, hampering fundraising and mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

For years, the cleantech revolution has attracted big bucks, echoing investment booms that benefited from the zeitgeist around organic food, shale oil and gas, and sustainable fishing ventures.

"I think of the most recent years in the power space and renewables specifically a bit like the shale boom in 2008-2010," said Bernadette Johnson, head of power and renewables at analytics firm Enverus.

A decade of low interest rates meant borrowers could raise cheap debt to build projects and juice returns. But an era of plentiful materials and financing has given way to constraints.

With the US Federal Reserve projected to raise headline rates to around 5.5 per cent this year and European hawks starting to posit peak rates above 4 per cent, returns are squeezed.

"Some people are starting to lose money. Others are definitely making money but it's evolving," Johnson said.

RECUT THE ECONOMICS

Even with President Joe Biden's Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and potential state support in Europe, private equity investment in alternative energy including battery and energy conservation technology is heading for the slowest quarter since 2020, according to Refinitiv data.

Refinitiv also projects the value of M&A this quarter will total $5.6 billion, from $17.7 billion last and almost in line with the depths of Covid total between April and June 2020.

Utilities in the US and Europe have been selling parts of their renewables businesses to fund network upgrades without offering new equity or damaging credit ratings through debt sales.

Consolidated Edison sold its US renewables business to Germany's RWE for $6.8 billion in October. Since then, similar moves have struggled against the new market reality.

Duke Energy said last month a divestment of its renewables business, which it valued in November at $4 billion, was taking longer than expected.

Financial investors traditionally took stakes in operating renewables projects to avoid risks of construction delays and ensure stable returns.

As competition heated up in recent years, projects started being sold earlier, pre-construction.

That construction now costs substantially more.

"Having seen inflation and the cost of debt go higher, in many cases there has been a need to go back and recut the economics," said Adi Blum, a managing director at BlackRock, told a CERAWeek panel.

Germany's PNE could explore selling its US solar and wind business due to high project costs, sources told Reuters this week, hoping IRA tax credits could attract suitors.

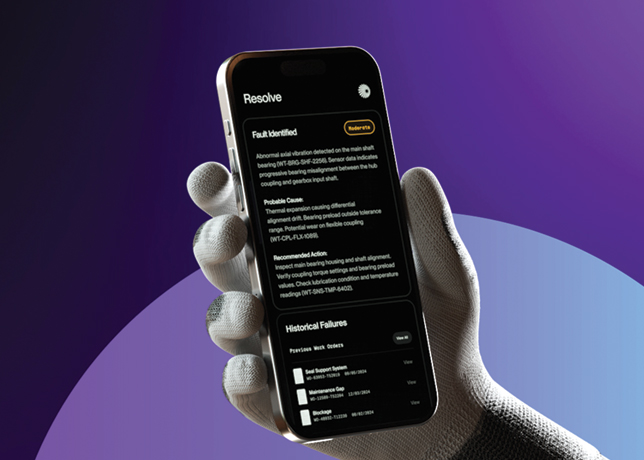

One other consideration is older plants are starting to show signs of wear, requiring costly repairs or upgrades.

"The pool of operators or investors out there who can handle those changes and generate improvements is much smaller than you think," said Angelo Acconcia, partner at investment firm ArcLight Capital Partners.

"We came out of a cycle of low interest rates in which it was easy to look for an asset, buy, build, de-risk and sell cash flows. Now the transactions we are seeing are for growth, they are not based so much on cashflows," said Oscar Perez, investment director at fund manager Qualitas Energy. -Reuters