Iran’s unsold oil still kept on board tankers

Iran’s unsold oil still kept on board tankers

INCREASINGLY hard-pressed to find buyers for its petroleum, Iran has been routinely switching off satellite tracking systems on its sea-bound oil tankers for more than a month, in what US officials and industry analysts describe as a cat-and-mouse game with Western governments seeking to enforce sanctions on Iranian exports.

The unusual tactic was begun in early April and affects a quarter of Iran’s tanker fleet, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), which has been monitoring the practice. The move, a violation of maritime law, is only modestly effective in cloaking 1,000-foot-long tankers as they ply the oceans in search of open ports and willing buyers. But it underscores Iran’s precarious position as it faces ever-tighter Western restrictions against its oil industry, which provides the bulk of export and government revenue.

Hobbled by sanctions against its banks and a growing international boycott of its petroleum, Iran is seeing its revenue sag while its oil sits in storage depots and floats in tankers with nowhere to go, US security officials and diplomats say.

The country’s worsening prospects have encouraged Western governments. US officials say the building economic pressure increases the chances for a breakthrough in which Iran would agree to abandon elements of its nuclear program.

“They are increasingly isolated – diplomatically, financially and economically,” David Cohen, the Treasury Department’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, says. “I don’t think there is any question that the impact of this pressure played a role in Iran’s decision to come to the table.”

Cohen notes the cascading effects from Iran’s oil crisis spreading to other parts of the economy as consumer prices and unemployment rates soar.

“The value of their currency, the rial, has dropped like a rock,” Cohen told a gathering at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “That has had a significant impact on Iran’s ability to pay for materials for the nuclear program, and, more broadly, it puts pressure on the leadership.”

Whether Iran is prepared to make significant concessions is unclear. But there is little doubt about the toll being exacted by sanctions.

“It has definitely hurt Iran,” says Amrita Sen, a London-based commodities analyst with Barclays Capital. “No doubt about that.”

One key impact of recent sanctions has been to choke off shippers’ access to maritime insurance, nearly all of which is underwritten in Europe, Sen says. That has made Iran ever more dependent on its own fleet of 39 tankers, including 25 super-tankers, according to IEA figures.

Those ships also face mounting obstacles. After coming under pressure from the United States, the ship classification society Lloyd’s Register said in late April that it would close its office in Iran and stop certifying the safety of Iran’s ships. The certification is needed by ships seeking entry at most of the world’s ports. Late last year, another leading classification society, Norway’s Det Norske Veritas, ended its relationship with Iran under US pressure.

An IEA report says Iranian crude output was still relatively high, at 3.3 million barrels a day in April, down slightly from last year. But the agency said much of Iran’s unsold production is ending up in onshore and floating storage.

Estimates of Iranian crude added to floating storage in March and April have ranged from 450,000 to 800,000 barrels a day, the IEA says. An additional 20 million to 25 million barrels have been added to onshore storage facilities in recent months.

While countries such as Turkey and South Africa have ramped up imports from Iran ahead of the July 1 sanctions deadline, some of Iran’s biggest customers, including Japan and South Korea, have been gradually reducing Iranian crude imports. Europe has cut its imports from Iran to less than half its earlier level of 700,000 barrels a day.

In addition, India has trimmed its oil purchases from Iran, which last year covered 10 percent of India’s oil consumption. During her visit there last week, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton pressed India to further reduce its oil imports from Iran.

Members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries are filling in the gap. Motivated in part by high world oil prices, Opec crude supply in April rose 410,000 barrels a day, with Iraq, Nigeria and Libya providing about 85 percent of the increase, according to a report.

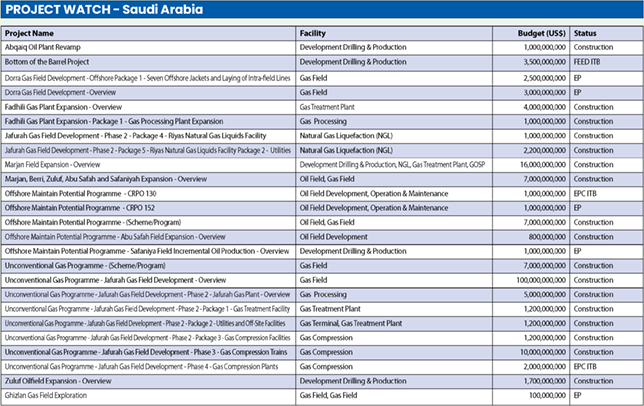

Saudi Arabia’s crude oil production in April was unchanged at the relatively high level of 10 million barrels a day, but the IEA report says the kingdom has been offering price discounts for its Arab Light crude, which is widely sold to Asia. That could encourage countries such as China to shun Iranian oil.

“They can’t move the stuff, and they’re really hurting,” says a senior State Department official with access to intelligence on Iran’s oil shipments. He spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak publicly about the matter.

Analysts warn, however, that Iran might have an easier time selling its oil during the third quarter of the year, when global oil consumption usually peaks. At this time of year, many refineries take advantage of relatively slow oil use to close for maintenance.