Offsets have attracted attention from

Offsets have attracted attention from

The only way to bring transparency and certainty to the carbon offset market is through better governance and for more participants to get involved, driving competition for high-value products, says a report by Westwood Global Energy Group

Early this year Chevron Singapore launched a carbon offset programme for its Singaporean Caltex brand. It’s a neat idea.

Customers feeling queasy about their vehicle emissions can use their petrol pump loyalty points to offset their greenhouse gas footprints through investments in carbon reduction schemes approved by the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), an independent verification programme.

Offset schemes such as this hold considerable promise for companies that cannot immediately switch to zero-carbon operations.

Whole industries are adopting an offset approach to reducing their emissions, with a prime example being the Carbon Offsetting Scheme for International Aviation that was launched in 2020.

The concept is simple. For every tonne of carbon you emit, you pay for the removal, reduction or avoidance of an equivalent amount from the atmosphere, for example by planting forests, restoring peat bogs, reducing methane leaks or scaling up technologies such as direct air capture (DAC). These activities generate a financial product—a credit—to use in offsetting emissions.

In theory, if all emissions were cancelled out using offset schemes, then we could stop global warming in its tracks tomorrow.

The oil and gas industry could carry on producing and selling oil and gas indefinitely because all those carbon emissions would be taken care of.

Not only that, but offsets can do more than simply solve climate change. By helping preserve forests and other natural habitats, offsets can safeguard biodiversity and deliver other environmental benefits, as well as creating income streams for local populations tasked with stewardship of those habitats.

Given these benefits, it is no wonder that offsets have attracted attention from oil and gas players.

In August 2020, for example, Shell Australia bought Select Carbon, a provider of nature-based solutions—schemes that remove emissions by fostering forests, grasslands, wetlands and the like.

BP followed suit in December 2020 with the acquisition of US forest offset developer Finite Carbon.

Eni, TotalEnergies and Chevron have partnered with offset companies. In April 2021, Lundin Energy used offsets certified by the VCS to claim it could produce carbon-neutral green barrels.

All this activity would be highly laudable if it were not for one small detail: carbon offset schemes today are often far from perfect.

In 2021, an investigation by The Guardian and Greenpeace concluded that carbon offset schemes approved by the VCS were not fit for purpose. "There is room for projects to generate credits that have no impact on the climate whatsoever," said the investigators.

EFFECTIVENESS IN QUESTION

Verra, the US non-profit that administers the VCS, has said the investigation was "profoundly flawed" and did not account for recent amendments to the standard.

However, the spat highlights the fact that the effectiveness of many carbon offset schemes—and particularly those that use nature-based solutions—is still questionable.

You might assume a tree-planting programme will soak up many tonnes of carbon, for example, but how do you guarantee the trees won’t get chopped down or burnt in the coming decades?

Similarly, how do you prove those trees are there thanks to the carbon offset scheme and would not have sprouted in any event?

To be fair, the nascent carbon offsets industry is aware of these shortcomings and is working to overcome them.

The most obvious way to do this is by factoring the effectiveness of different carbon reduction methods into offset pricing.

DAC, for example, is about as robust as you can get in terms of carbon reduction. You can use it to literally pull a tonne of CO out of the air and store it underground for millions of years.

That certainty comes at a price, however, with estimates of the technology costing, at least, five times more per tonne than reforestation, for example.

Using today’s technology, the cost of eliminating carbon using DAC and storage is so high you might as well not emit the carbon in the first place—which is sort of the point.

Nature-based solutions are inherently a lot less certain, but it also costs a lot less to plant trees or preserve wetlands.

Hence, one line of current thinking is to assume the value of nature-based solutions should be discounted to factor in their uncertainty.

Instead of offsetting a tonne of emissions with a tonne of forest, you buy 10 tonnes of forest on the assumption that 90 per cent of the trees will never survive.

Soon it is hoped that such considerations will lead to the emergence of robust offset schemes where you can be certain that the money spent really is having an impact on global emissions.

HANDLE WITH CARE

These schemes could have a transformative impact not only on climate change but also on the preservation of natural habitats and the communities that depend on them.

But there are two important points to bear in mind. The first is that, whether you are using carbon capture and storage (CCS) or trying to preserve a forest for hundreds of years, permanent and verifiable carbon offsets are not going to be cheap.

The second point is that we are still a long way off having scalable, permanent and verifiable offset schemes today.

Even ardent defenders of carbon offset mechanisms admit that today’s markets are like the Wild West, with thousands of people operating ‘bogus’ schemes.

Does this mean carbon offsets should be abandoned? Not at all.

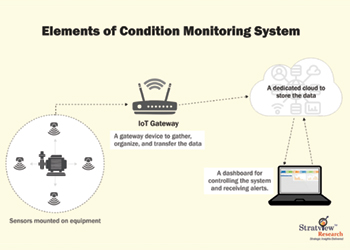

The only way to bring transparency, integrity and certainty to the market is through better governance and for more participants to get involved, driving competition for high-value products.

The COP26climate talks started to address some of the key issues, and efforts are being made by the private sector to enhance the credibility of markets underpinning offsets, but there is more work to do. And whether those participants should include oil and gas companies, at this stage, is a different question altogether.

With even supposedly high-quality certification programmes such as VCS facing scrutiny, there could be significant reputational risk in oil and gas companies claiming to reduce emissions through carbon offset schemes, unless they involve techniques such as CCS that leave little room for doubt.

And if the idea, as in Chevron Singapore’s case, is to make offsets available to customers in a bid to reduce Scope 3 emissions, then the shortcomings of today’s schemes should be made abundantly clear.

Oil and gas can certainly play a role today in supporting offset markets so they move rapidly towards maturity.

But using them to claim effective carbon reductions at present is only too likely to result in accusations of greenwashing, which won’t benefit offset markets—or the oil and gas companies using them.

.jpg)