A high-level meeting at Petropars

A high-level meeting at Petropars

A PIPELINE deal with Iraq is the latest move by Iran to boost exports from its natural gas sector, which is woefully underdeveloped given the country’s massive reserves.

Iran wants to increase gas exports in order to diminish reliance on crude oil sales, which have halved in the past year under stringent US and EU sanctions.

Javad Owji, the managing director of the National Iranian Gas Company, announced new deals with Turkey and Iraq, and claimed that Iran would increase gas exports to about 100 million cubic metres per day (mmcmd) by next year, from a current 35 mmcmd. However, obstacles remain and the Iranian gas sector will continue to fall well short of potential.

According to Owji, Iran exports 30 mmcmd of natural gas to Turkey (10.9 billion cubic metres (bcm) annually), earning more than $3 billion yearly.

These figures are far higher than those given in the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013, which puts Iran’s total exports of gas by pipeline in 2012 at 8.4 bcm, with 7.5 bcm going to Turkey.

Furthermore, Iran actually imports more natural gas (mostly from Turkmenistan) than it exports, according to the Statistical Review and the US Energy Information Administration.

Owji says that Iran planned to start supplying 24 mmcmd to Iraq within a year via a pipeline under construction.

Boosting exports to Turkey and Iraq would help Iran’s fiscal accounts, but would only partially compensate for lower oil revenue. If priced at European market rates, the deal with Iraq would be worth around $3.7 billion per year.

However, sanctions have reduced Iran’s oil exports by around 1 million barrels per day (mbpd), which, even at $90 per barrel, amounts to almost $33 billion per year.

Iran has been slow to exploit its gas reserves of around 33.6 trillion cubic metres (tcm), the world’s largest, slightly ahead of Russia’s 32.9 tcm, and 18 per cent of the world total (the Statistical Review).

|

|

The Ceyhan terminal in Turkey ... ready to |

Iran’s gas output in 2012, according to the Statistical Review, was just 160.5 bcm, a 5.4 per cent increase on 2011, but only 4.8 per cent of the world total. Most goes to the home market, with domestic consumption of 156.1 bcm, 1.4 per cent higher than 2011.

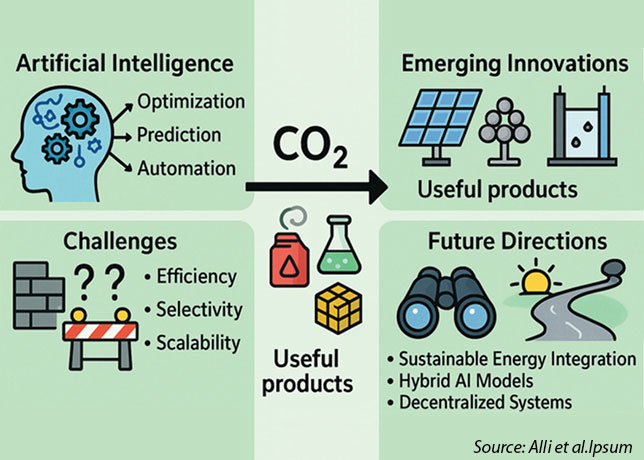

The main problem facing Iran is that extracting and exporting gas requires a relatively high level of technology, especially in liquefaction, the most flexible and efficient means of transportation and export.

Producing liquefied natural gas (LNG) depends largely on patents held by US companies, and Iran’s earlier strategy of joint projects with international majors – including France’s Total and UK-Dutch Shell – ran into problems as a result of the reluctance of these operators to incur the wrath of the US government by passing on technology. A further problem is Iran’s lack of finance after the drying up of foreign investment.

Iran’s largest gasfield is the massive South Pars field, contiguous with Qatar’s North Dome field. Iran originally divided South Pars into 28 phases and contracted many to international companies, who withdrew under US pressure and were replaced by Chinese or Iranian companies with very little relevant experience. Hence, whereas Iran has yet to develop LNG facilities, Qatar, with lower reserves, at 25.1 tcm, in 2012 exported 105 bcm of gas as LNG (the Statistical Review).

The deal with Iraq, worth a reported $3.7 billion annually, is aimed at easing the country’s electricity shortages. Iraq will import 24 mmcmd (8.7 bcm per year) in a four-year contract for two power plants in Baghdad to generate 2,500 MW.

The 500km-long pipeline, passing through the volatile province of Diyala, is 90 per cent complete, and due to be finished in September. Iraq’s current electricity production falls well short of the 14,000-15,000 MW it requires, and it is already importing around 1,000 MW from Iran.

Iran has been examining many projects for pipelines as an alternative to LNG. The most important, to Pakistan, is scheduled to open in December 2014, with an annual capacity of 22 bcm of natural gas.

The pipeline was originally intended to include India, who withdrew in 2009 under US pressure and a year after a nuclear deal with the US. By early 2012 Iran had completed its own leg of the pipeline from Assalouyeh, in Bushehr province, to the Pakistan border, and in November announced that it would lend Pakistan $500 million of the $1.5 billion required to build the 780-km Pakistani leg.

Pakistan faces energy shortages that have produced crippling electricity cuts for homes and businesses, but could still face significant US opposition in going ahead, with the US offering assistance in importing LNG from Qatar and for hydroelectric power.

The US also has strong influence with international bodies important to Pakistan, like the World Bank and the IMF. Pakistan may also face problems with Saudi Arabia, which has supplied oil on favourable terms and which tends to seek to counter Iranian influence.

In 2012 Iran said that it intended to increase South Pars gas production above Qatar’s output by 2016, but gave little idea how it would overcome substantial technical and financial challenges in meeting a target of 800 mmcmd.

A deputy oil minister claimed in April that South Pars was producing 300 mmcmd (far higher than BP’s estimates for Iranian production). In practice, South Pars projects awarded to both Iranian and Chinese companies are behind schedule.

There were originally three LNG projects linked to South Pars. Shell and Spain’s Repsol YPF had to withdraw in 2010 from “Persian LNG”, a liquefaction project based on phases 13 and 14 of South Pars. Total withdrew from the “Pars LNG” venture, linked to phase 11, in 2009, and was replaced by the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), who pledged completion within 52 months, but dragged its feet and reportedly had the contract terminated in early 2013.

CNPC has other energy projects in Iran, including the Masjed-i-Suleiman, North Azadegan, South Azadegan, and Kuhdasht oilfields, but its subsidiary, Petrochina, is listed in New York and so the company is vulnerable to possible US action. This may partly explain its slow progress with projects in Iran.

Phase 12 of South Pars has been separated from the original “Iran LNG” scheme and is now in the hands of Iran’s Petropars and being developed alongside Phase 19.

Petropars said in April that phase 12 would be finished by March 2014 and phase 19 by March 2015, producing together 52 bcm per year. Iranian officials have suggested that “Iran LNG”- for which storage tanks have been built by an Iranian company, Panahsaz – will continue with gas from Phase 11, but it is not clear when that phase will be operational or how Iran will acquire the technology required to produce LNG.

Even if not hampered by sanctions, Iran would need many years to reach a planned export capacity of at least 40m tonnes per year of LNG (55.2 bcm). And in the meantime, Iran faces a further challenge in the spread of LNG projects across new producers (such as Australia, North America and the east coast of Africa). Movements away from oil indexed prices may also mean that Iran’s gas exports may not be as rewarding as it expects.

LNG plants under construction worldwide will boost total export capacity by 32 per cent by 2018, data shows, with 93.5m tonnes of capacity added to the existing 296m tonnes.