Saudi Higher officials at the iktva Forum and Exhibition

Saudi Higher officials at the iktva Forum and Exhibition

Saudi Arabia is not leaving any stone unturned to reach its net-zero goals, but its efforts have to be consistent with economic development and minimum impact to it

After the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia set 2060 to achieve net-zero goals and national oil company Aramco announcing it would do it by 2050, there is clear expectation from all stakeholders to share and uphold those ambitions.

Aramco CEO Amin Nasser especially called upon partners to its localisation programme iktva (In-Kingdom Total Value Add) to share their 'passion for sustainability and strengthen ESG performance'.

These calls build on the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 by uniting all sustainability efforts to increase reliance on clean energy with five key focus areas, including the reduction of carbon emissions, protecting oceans, defending wildlife, preventing desertification, and increasing recycling. This approach is complemented by the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) launched in November 2021.

Saudi Arabia has been actively engaged in joining global forces to addressing climate change and managing energy transition both at international and domestic levels.

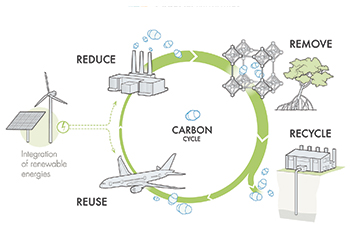

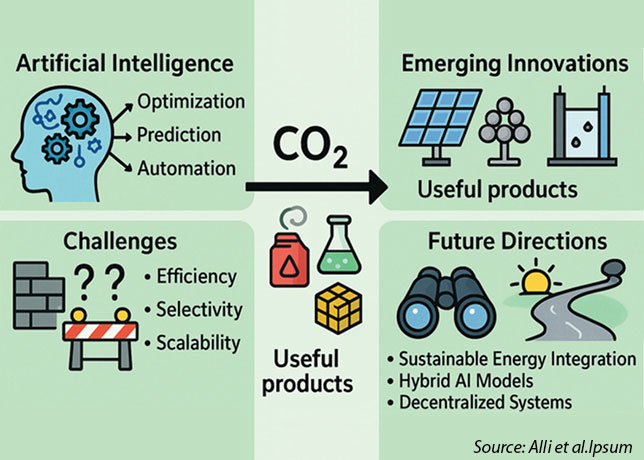

In line with Vision 2030, which aims to diversify the economy by substantially reducing reliance on oil, the Kingdom has adopted a circular carbon economy (CCE) approach

In this context, it is developing alternative energy sources and has embarked on several hydrogen development initiatives.

Being one of the largest oil producers in the world, Saudi Arabia has always been wary of its emissions.

Policies to reduce flared gas have been implemented since the 1970s, and rigorous monitoring under Aramco’s methane leakage detection and repair programme brought down methane intensities to as low as 0.06 per cent in 2018

Saudi Arabia, however, is ranked as having one of the lowest methane intensity rates globally

|

|

The 300-MW Sakaka solar power plant in Al Jouf Province |

According to data released in June 2021 by the energy data provider Enerdata, the Kingdom’s CO2 emissions from fuel combustion decreased by 3.3 per cent, from 508.3 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) in 2019 to 491.8 megatonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) in 2020.

According to a report, entitled 'What Drove Saudi Arabia’s 2020 Fall in CO2 Emissions?' by the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) Saudi Arabia is one of four G20 emerging economies whose change in GDP has exceeded its change in CO2 emissions on a year-on-year basis.

In 2020, across most of the G20, there was a massive drop in CO2 emissions from fuel combustion, largely in line with the fall in economic activity measured by GDP.

Emissions can be understood as a function of four major components: population growth, per capita economic growth, changes in the energy intensity of the economy, and emissions intensity of the energy mix. This equation, known as the Kaya identity.

Considering the last two for brevity, Saudi Arabia’s energy intensity performance has fluctuated in recent years, but 2020 appears to have followed a similar pattern to 2019. In 2020, the Kingdom’s energy intensity increased by an estimated 1.4 per cent.

Energy intensity generally improves as a country’s production processes become more energy-efficient, or as a country moves away from energy-intensive manufacturing toward services.

For comparison, to reach the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) target of doubling the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency, countries’ energy efficiency should improve by 3 per cent each year, on average.

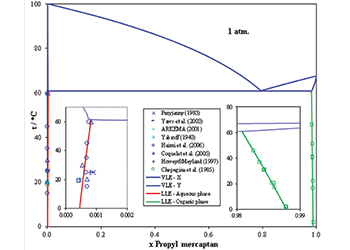

Alternatively, the carbon intensity of Saudi Arabia’s energy mix has decreased since 2017, albeit at a decelerating pace: In 2017, its carbon intensity decreased by 4.2 per cent, whereas in 2020, this rate was only 0.6 per cent.

The carbon intensity of the energy mix is influenced by two drivers: the emissions intensity of the fossil fuels used and the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix.

There has been year-on-year changes in CO2 emissions from fuel combustion in the Kingdom over the past decade.

Three broad trends can be identified. First, CO2 emissions from natural gas combustion have been increasing steadily over the past 10 years. Second, CO2 emissions from oil products have been falling since 2015, which, third, has driven an overall decrease in fossil fuel combustion-related CO2 emissions.

The year-on-year fall in oil-related emissions in 2020 was steep, at 5.4 per cent, but this was on par with the reduction in 2017 (5.3 per cent) and less than the fall in 2018.

Upon examining CO2 emissions by sector, it was found that overall the industrial sector is the largest contributor, with a 47.2 per cent share in 2020, followed by the energy (27.7 per cent) and transport (24.1 per cent) sectors.

Emissions fell in all sectors year-on-year in 2020, except in industry, which increased by 2.9 per cent.

Furthermore, a detailed look at emissions in the energy/power sectors show that CO2 emissions from power generation, which account for approximately 80 per cent of energy sector emissions, have been falling since 2015. These are driven by decreasing emissions from oil-fueled electricity generation.

Fuel switching to natural gas took place at the fastest rate between 2016 and 2017, but this appears to have slowed down in 2018. The year 2020 continued the trend of falling overall CO2 emissions from power generation (-3.3 per cent), while the share of natural gas has remained at slightly over 50 per cent since 2018.

In contrast to the overall declining CO2 emissions trend in the energy sector, there was a large increase (11 per cent) in emissions related to refining.

These emissions have consistently increased from 2015 onward due to capacity expansions and upgrades in existing refineries, in addition to new refineries coming online.

During this period, refining from total energy sector emissions increased from 8.5 per cent to 19.5 per cent.

• CCE Index: Kapsarc developed the CCE Index to help develop metrics to support policymaking. The index promotes further understanding of the CCE concept and the idea of adopting a holistic approach to managing emissions across energy systems and economies, and achieving carbon circularity.

In the region, Saudi Arabia’s has an aggregate CCE Index score of 40.16, second to UAE’s 42.09.

However, the country’s performance score, which gauges how countries are performing presently on the different CCE activities, is 40.63, more than the 34.83 score of UAE.

CONCLUSION

Despite the agreement to move towards a sustainable energy future, there are complexities and challenges to consider.

In a recent interview, Nasser acknowledged that the current transition is not going smoothly.

Speaking remotely at the B20 conference in Indonesia, he said investments in hydrocarbons had to go hand in hand with new energies as demand for conventional energy would likely prevail for, 'quite some time'.

'As the global economy has started to recover there has been a resurgence of demand for oil and gas but since investment in oil and gas has fallen supplies have lagged which is why we see very tight markets in Europe and parts of Asia,' he said, stressing that he was not advocating for a change in climate goals.

'I am proposing that investment in both existing and new energy be continued until the latter is developed enough to realistically and significantly be able to meet rising global energy consumption,' he clarified.

By Abdulaziz Khattak

.jpg)