Natural geologic hydrogen is created within certain rock formations

Natural geologic hydrogen is created within certain rock formations

White, gold or natural hydrogen holds huge potential as a clean fuel. Owain Jackson, CEO and co-founder of H2Au.co, explains why we need to actively go looking for it

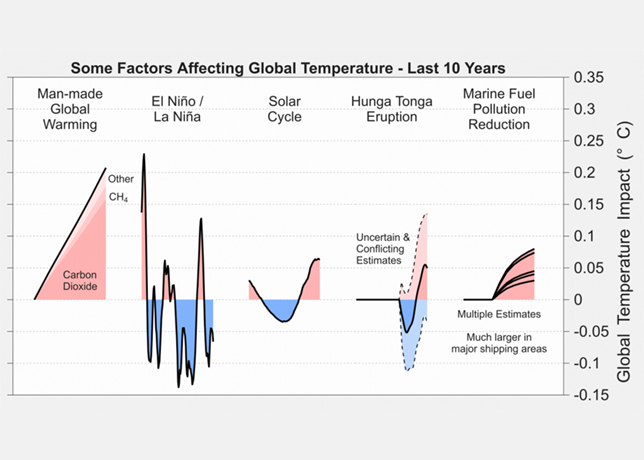

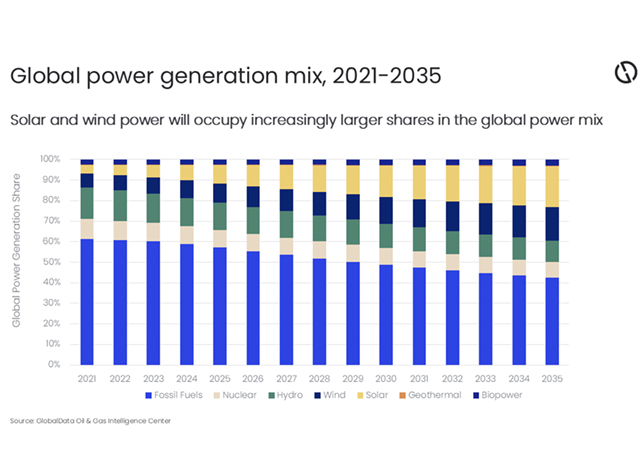

Bound by net zero commitments, the vast majority of the world’s countries are looking for clean energy to displace fossil fuels from their energy mix.

Much of the focus is on renewable electricity, but for energy-intensive sectors and those that are hard to decarbonise, hydrogen is the clear alternative.

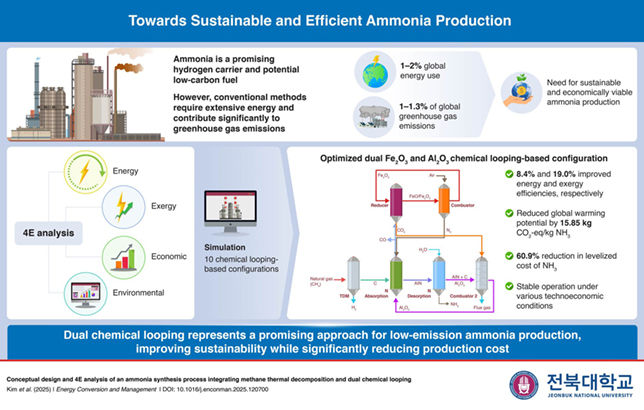

Much attention has been focused on the so-called rainbow. For instance, green hydrogen can be commercially manufactured through electrolysis or plasmolysis (provided the process is powered by renewable energy); whereas blue, turquoise and grey hydrogen can be synthesised from a range of fossil fuels.

There’s even pink hydrogen, generated using nuclear-powered electrolysis.

Despite this bewildering range of manufactured hydrogen sources and processes, it’s doubtful that any single option could achieve sufficient volumes or economics to match growing hydrogen hype.

AN ABUNDANT ENERGY SOURCE

In recent years, however, an alternative source of hydrogen has re-emerged that could exceed the world’s demand – potentially for hundreds of years.

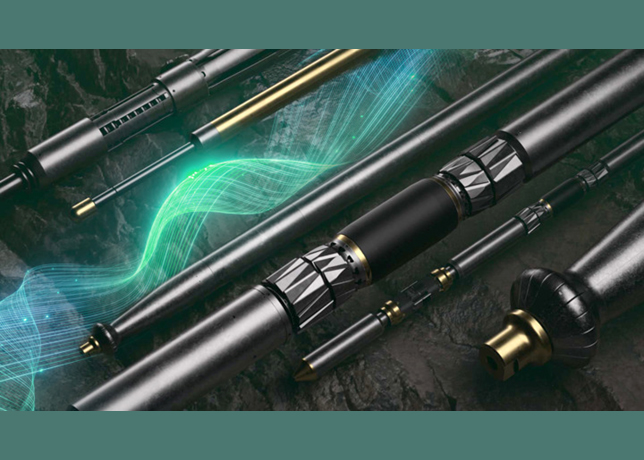

Natural geologic hydrogen, also known as white or gold, is exactly that: Pockets of the gas created within certain rock formations, theoretically just waiting to be extracted and used.

Geologic hydrogen is produced naturally within the earth as the result of several processes, but as much of 80 per cent of it is thought to be the result of serpentinisation.

Here, water reacts with rocks rich in iron and magnesium in the earth’s crust, or on the ocean floor.

|

Exploring hydrogen sources for clean energy |

These reserves of gas can be trapped by impermeable layers, accumulating into significant volumes over time.

As a primary, rather than manufactured energy source, natural hydrogen is abundant, low cost, low carbon and sustainable.

We’ve long known of this resource. One hundred years ago. Australian drillers discovered significant amounts of hydrogen at the Ramsey and American Beach wells.

It’s been found accidentally whilst drilling for oil and gas reserves since then, but it wasn’t until 1987 – with the discovery of a hydrogen well in Bourakebougou, Mali – that people sought to proactively exploit natural hydrogen’s potential value.

And what potential. The US Geological Survey has estimated that around 5.6 trillion tonnes of geologic hydrogen is already trapped underground around the world, and that another 15-31 million tonnes are created each year.

That, it says, is "twice the amount of energy in all the proven natural gas reserves on Earth".

A READY SOLUTION

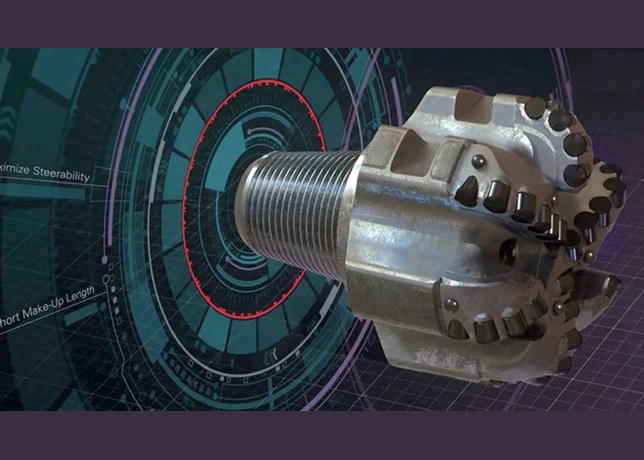

Importantly, extracting this hydrogen isn’t an unrealistic fantasy. The International Energy Agency (IEA) assesses the technology readiness level (TRL) for natural hydrogen extraction at 6-7 (where nine is the highest).

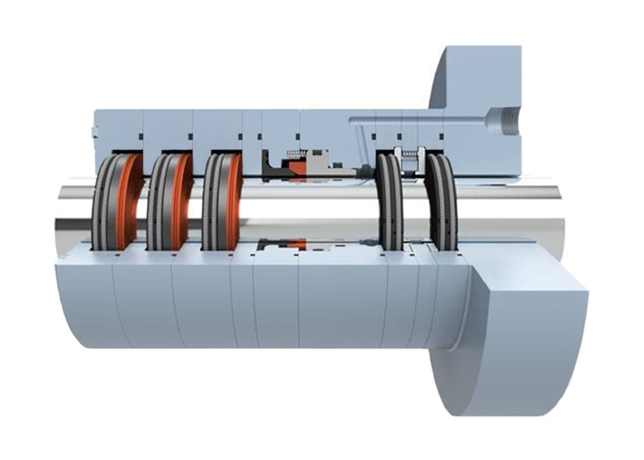

Indeed, much of the required expertise and equipment for hydrogen extraction already exists in the petrochemical industry and there is arguably no ‘first of a kind’ technology required to develop and scale the natural hydrogen industry.

That’s a stark contrast to the manufactured hydrogen sector, where many plays rely on novel technologies, yet to be de-risked and proven at scale.

Natural hydrogen is entirely viable as a primary energy source. It has already seen limited production in Mali. However, it could be extracted and used at scale within a few short years.

H2Au’s view is that, if realised at its full potential, natural hydrogen could address a $6 trillion per year energy market, and save over seven gigatonnes in emissions annually by 2050.

So, what’s the holdup? We’ve long known that the hydrogen reserves at Mali wouldn’t be a one-off.

Until recently, however, all of the world’s discoveries of natural hydrogen have been accidental or incidental, often arising during prospecting for other gases or resources.

Yet we know, from hundreds of years of fossil fuel and mineral exploration, the type of geologies and territories in which hydrogen is formed and trapped. So what’s to stop us actively going looking for them?

EXPLORING FOR HYDROGEN

H2Au’s founders first visited the hydrogen well at Bourakebougou in 2008 long before many were even thinking about the potential of natural hydrogen.

The US Geological Survey began formal investigation of natural hydrogen resources in 2021.

By 2024, active exploration campaigns were ongoing in Australia, Brazil, Colombia, the US, and various countries in Europe and Asia.

Businesses at the forefront of this exploration, such as H2Au, must first identify regions that are known or suspected to contain reserves of natural hydrogen, then secure exploration and production licences.

It’s one thing to suspect the presence of hydrogen, but identifying commercially viable reserves depends on deep experience and geological expertise.

Much of our own know-how and model building comes from analysing the well at Mali and having first-hand knowledge of the geology in that area.

As a geoscience-led team, H2Au already has both the internal experience and external partnerships to acquire and interpret the vast data set, such as seismic surveys, required to de-risk exploration.

Supply and service chain collaboration is invaluable here in moving dots on a geology map through the exploration phase and towards production.

This includes actively partnering with oil and gas drilling experts to leverage and adapt their tried and tested techniques to safely develop hydrogen wells and infrastructure.

The key to successfully locating natural hydrogen, and then extracting it at scale, is blending in-house IP in resource discovery, with operational exploration experience across diverse cultures and land-uses.

In other words, having both the science to find natural hydrogen, and the ground level experience to execute its commercial extraction.

The simplicity of natural hydrogen extraction, and its similarity to established oil and gas industry practices, means that its investment and risk profile depends on a well understood exploration hit rate, rather than whether novel manufacturing technologies will actually work.

And once you find natural hydrogen, the opex costs are very low. Unlike manufactured hydrogen, there’s no ongoing need for large amounts of energy, water and complex plant maintenance.

Given the vast amounts waiting to be discovered, natural hydrogen is rapidly emerging as a compelling and exciting prospect.

Low in technological risk, and with minimal operating costs, it presents as a convincing answer to the world’s energy demands, and in turn holds major promise for global carbon reduction and net-zero goals.

By Abdulaziz Khattak

-is-one-of-the-world.jpg)

-(4)-caption-in-text.jpg)