Wind and solar power expanded by 16 per cent in 2024

Wind and solar power expanded by 16 per cent in 2024

Despite record growth in renewables, the Middle East’s energy trajectory underscores the global paradox of rising emissions alongside clean power expansion, Gael Rouilloux tells OGN

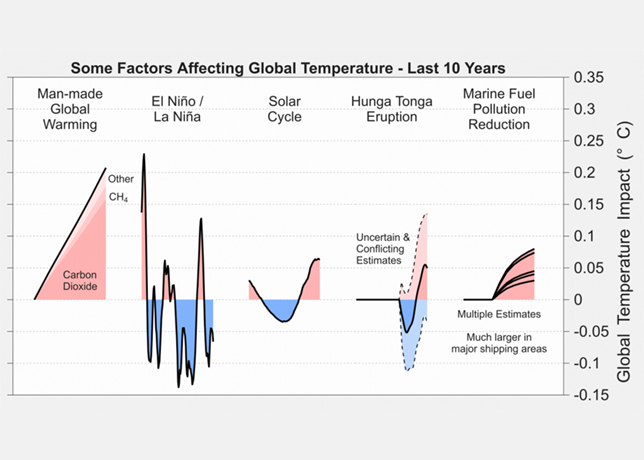

In a year when average air temperatures consistently breached the 1.5 deg C warming threshold, global CO2-equivalent emissions from energy rose by 1 per cent, marking yet another record, the fourth in as many years.

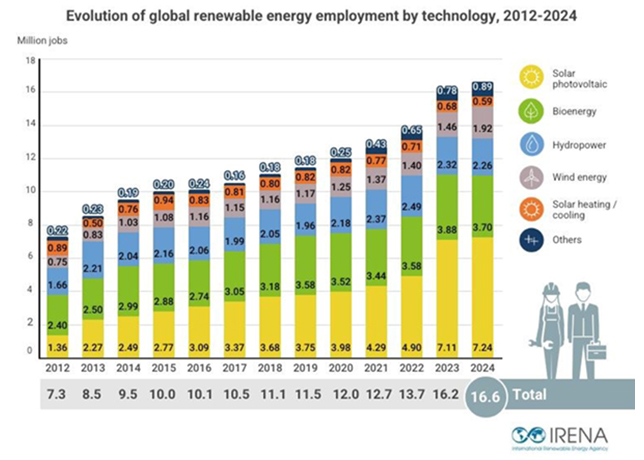

Wind and solar energy alone expanded by an impressive 16 per cent in 2024, nine times faster than total energy demand.

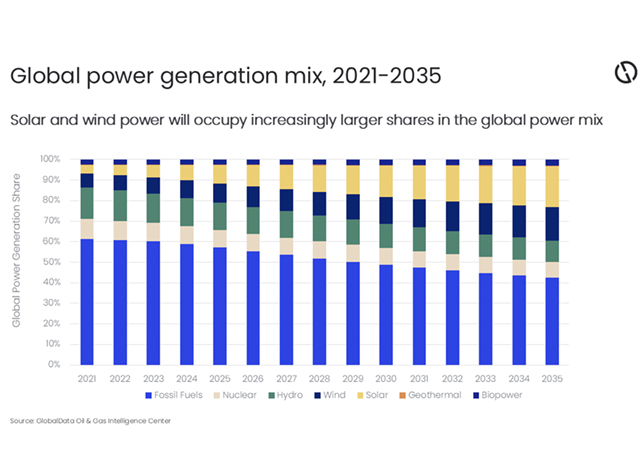

Yet this growth did not fully counterbalance rising demand elsewhere, with total fossil fuel use growing by just over 1 per cent, highlighting a transition defined as much by disorder as by progress.

This first complete look at global energy data for 2024 was offered in the 74th edition of the Statistical Review of World Energy, which was released by The Energy Institute (EI), in collaboration with Kearney and KPMG in late June.

In an exclusive interview with OGN energy magazine, Gael Rouilloux, Middle East and Africa Lead, Energy and Process Industry at Kearney, explains the complexities of the global energy transition.

Below are excerpts from the interview:

Despite renewables growing nine times faster than global energy demand, fossil fuel use still rose in 2024. What does this dual growth trajectory say about the actual pace and direction of the energy transition?

This reflects one of the core complexities of the energy transition. In 2024, geopolitical tensions and extreme weather events reshaped the energy landscape, putting energy security, resource access, and technological sovereignty ahead of climate targets.

Electrification grew by 4 per cent, outpacing overall energy demand growth of 2 per cent, a trend sustained for the past decade.

Wind and solar expanded by 16 per cent, led by Asia Pacific, with China responsible for 91 per cent of regional growth and 57 per cent of global growth.

Natural gas demand rose 2.5 per cent globally, while oil use remained flat in OECD markets, however, climbing 1 per cent in non-OECD countries.

Coal consumption hit a record high, with 83 per cent in the Asia Pacific and 67 per cent of that in China.

Although natural gas is less carbon-intensive than oil in power generation, global greenhouse gas emissions still increased by 1 per cent in 2024.

Middle East energy-related CO2 emissions reached a record high of over 3,000 million tonnes in 2024. What are the structural or policy-level barriers preventing decarbonisation in the region, despite rising investment in renewables like solar?

|

Gael Rouilloux |

While the Middle East has a long-term net-zero ambition driven by the ambition of several countries, the trajectory to reach that goal will be gradual.

The rapidly rising investments in renewables, coupled with the substitution of oil for natural gas in power generation, are movements in that direction that will gradually materialise into the overall emissions footprint.

This trajectory could potentially be further accelerated by policy incentives to decarbonise, for example, with the adoption of compliance carbon markets.

The Statistical Review of World Energy 2025 report mentions that all major energy sources hit all-time consumption records in 2024. Does this suggest that global energy systems are expanding rather than transforming, and how can policymakers respond?

The situations vary significantly per region; however, globally, we observe that there is limited "energy substitution".

We are living in a savvy world of energy addition, which means that GDP growth is not enough compensated for by energy efficiency.

Energy efficiency is the lever left behind in the energy transition, and significant efforts and policies will have to be deployed in that area.

Electricity demand grew faster than overall energy demand globally. How can countries in the Middle East leverage this ‘age of electricity’ to fast-track decarbonisation, particularly in urban and industrial sectors?

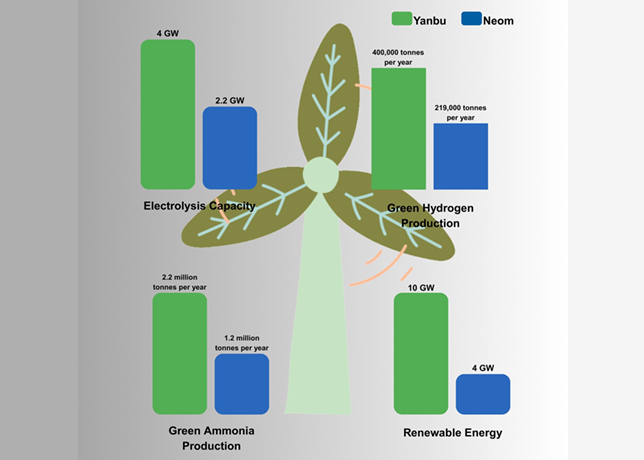

The Middle East has a natural advantage with both ample solar irradiation and wind resources, enabling the sequential lowest solar PV and onshore wind cost in the world in recent new capacity tenders.

The region has made huge developments in utility-scale solar PV and wind power capacity over the last 5 years, yet a large share of the power generation remains carbon-intensive.

Countries in the region are increasingly turning to substituting liquid fuels with natural gas and subsequently adopting CCUS to fully decarbonise.

The establishment of carbon markets may help further accelerate the decarbonisation in the region.

Given the Middle East’s 23 per cent year-on-year growth in solar power, what lessons can other developing regions learn from this scale-up, especially when facing challenges like grid integration, storage, and investment?

There are three key lessons. First, investor confidence hinges on bankable projects that deliver competitive returns while lowering the cost of solar power for host countries.

Second, early-stage solar adoption can advance rapidly without significant storage needs, enabling full use of low-cost solar before storage becomes necessary.

And third, when storage is required for grid balancing, applying the same independent power producer model as solar plants can ensure competitive project economics.

One of the stark messages of the report is that we are witnessing a ‘disorderly transition’. What specific regional disparities or geopolitical risks are most likely to derail coordinated climate action over the next five years?

Energy security prevails over climate change targets due to increasing geopolitical tensions. Energy transition is still happening, but within the very local boundaries of energy security.

For example, we observe a new momentum on nuclear power, and investments in all kinds of energy sources, including low-carbon sources.

Countries are developing local energy sources, tailored to each country’s unique circumstances and security needs.

The report introduces new mineral datasets, such as vanadium and tin, essential for energy storage and renewable tech. How significant is the availability of these resources for the pace of global clean energy deployment?

Mineral supply challenges stem from both the finite nature of deposits and the concentration of value chains in a tense geopolitical environment.

The main challenge for electrification is the possible scarcity of copper, nickel, and zinc in the mid-term.

Vanadium reserves are quite significant (estimated to last 175 years at current consumption levels), but essentially located in Australia, China, and Russia, for which access might be complexified due to geopolitical tensions.

With China contributing over half of the world’s new wind and solar capacity, how might the concentration of energy tech manufacturing in one region affect global energy security and supply chain resilience?

China’s scale advantage in deploying renewables also gives it a lead in commercialising related technologies.

A parallel can be seen in Li-ion battery production, driven largely by automotive demand.

For the Middle East, scaling industrialisation and localisation efforts will be key to building resilient supply chains and fostering domestic innovation.

From a Middle East perspective, oil production slightly declined in 2024, while energy demand and emissions rose. How do you see the region balancing economic dependence on oil with growing calls for carbon neutrality?

In 2024, the Middle East oil production slightly declined while oil consumption increased, resulting in overall lower oil exports.

Moreover, natural gas production and consumption in the region both increased, which contributed to meeting the increased overall energy demand while slightly improving carbon intensity through to substitution of oil in power generation.

COP28 called for a tripling of renewables by 2030, but the report suggests we’re off track. What immediate steps must governments and investors take to bridge the gap between climate ambition and on-the-ground progress?

On a standalone basis, renewables are already cost-competitive with thermal power generation.

However, as the sun does not shine during the night, the increase in penetration inevitably requires adding energy storage, which can affect the project economics and attractiveness of renewables.

Closing the gap between climate ambition and actual progress will demand a combined approach: Implementing policy measures, such as carbon markets, advancing storage technologies to enhance renewable economics, and placing greater emphasis on energy efficiency to reduce overall demand growth.

By Abdulaziz Khattak

-is-one-of-the-world.jpg)

-(4)-caption-in-text.jpg)