African countries need to increase collaboration amongst themselves

African countries need to increase collaboration amongst themselves

Cross-border cooperation will be imperative if the continent is to tack a happy ending onto the great African energy success story, writes NJ Ayuk, Executive Chairman, African Energy Chamber

Standard Bank’s recently released strategic discussion document reports that Africa holds natural gas in abundance, both onshore and off, accounting for more than 7 per cent of the world’s proven natural gas reserves.

While Algeria, Egypt, and Nigeria together can take claim to more than 80 per cent of Africa’s gas production per 2020 estimates, these figures are rapidly evolving, and much of the gas industry's attention is redirecting further south to Namibia, South Africa, inland to Zimbabwe, and to the east in Tanzania and Mozambique, which is home to the continent’s third largest store of natural gas.

The ‘South African Gas Optionality’ says that African gas production rates are also on the rise, and forecasts indicate this movement will continue for decades to come.

African gas output volumes have grown by 70 per cent since the year 2000 and, as outlined in Standard Bank’s report, should continue to grow to 2050, reaching a yearly output of approximately 520 billion cu m (bcm.)

The report also notes that with these relative newcomers to the African natural gas economy paired up with the more established producers in Nigeria, Senegal, and Mauritania in the west and with Algeria and Egypt covering northern Africa, practically the entire perimeter of the African continent could have liquefied natural gas (LNG) operations for the purposes of domestic use or export as early as 2027.

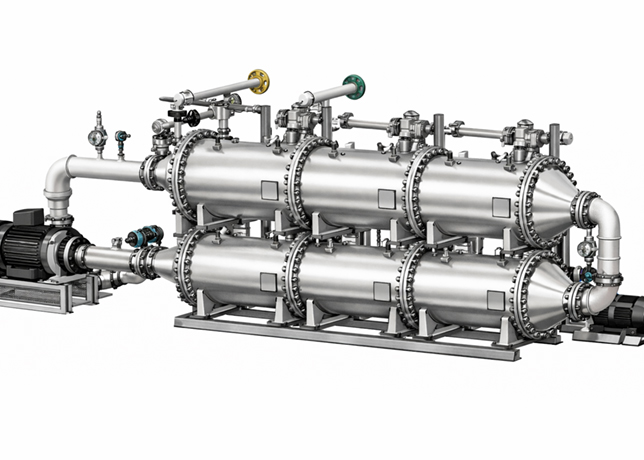

Factoring in Africa’s current LNG capacity of 72 million tonnes per annum (MTPA), the number of LNG facilities either in operation or advanced development, and the supportive role small-scale LNG (SSLNG) operators will play going forward, the report estimates that Africa’s capacity should increase by roughly 69 MTPA in the future.

The tendency of natural gas deposits to span borders – inherent to their location, size, and distribution – has, in many cases, already promoted international cooperation around the globe.

Where extraction was the concern, neighbouring nations have amicably negotiated operational territories, and it’s no different in Africa.

But when it comes to the feasibility of transportation, domestic distribution, and export, intra-African cooperation is more nuanced than merely the location of gas fields relative to borders.

Developing an effective and prosperous natural gas infrastructure and distribution network will require an earnest commitment to collaboration among nations.

Conveniently, potential cross-border partnerships literally crisscross Africa’s southernmost region.

Pipelines running from Lusaka, Zambia to floating storage regasification units (FSRUs) in either Lobito, Angola, or Walvis Bay, Namibia, could centrally connect with another running along the new TAZAMA refined product pipeline, which links Ndola, Zambia, to the active natural gas operations and the Coral floating LNG (FLNG) operation under development south of the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Further south in Mozambique, the rail network connecting Nacala to Lusaka, with stops in Malawi at Blantyre and Lilongwe, along with Chipata, Zambia, offers an inland transportation route.

With SSLNG trucking support, the connected railway from Beira to Lusaka with stops at Harare and Zave brings Zimbabwe into the fold, accommodating Invictus Energy’s recent promising finds in the Cabora Bassa Basin and completing Mozambique’s rail and SSLNG value chain.

Along the very active coastline of South Africa, a potential pipeline could run from East London, near the proposed site for Coega’s gas-to-power infrastructure, to the existing refineries at Mossel Bay and Cape Town.

Every African government, indigenous company, and individual citizen should cultivate the idea that they are also one people working together to profitably supply the world while improving conditions at home.